In a few frantic weeks early last year, online fashion retailers Asos and Boohoo upended years of British high street history as they picked over the remains of bankrupt groups Arcadia and Debenhams.

The absorption of brands with centuries of retail heritage by companies that came of age only in the 2000s seemed to encapsulate the narrative of the pandemic: store-based retailers would be eclipsed by nimbler online rivals far faster than anybody thought.

Since then, life has become much tougher for the fast fashion brigade. Cost pressures are mounting as the price of raw materials, labour and freight have risen sharply, just as demand has eased with the brands predominantly 20-something customer base facing the biggest income squeeze in years.

Shortly before the pandemic, Boohoo’s market value overtook that of British high street behemoth Marks and Spencer. It is now worth about a third of the value of its more traditional rival. Asos has also hit problems, warning in April of a sharp fall in sales growth and profits months after it fired its chief executive.

But while investors fret that the renewed pressures could make the fast fashion model unsustainable, the companies’ confidence is undiminished.

Last week, even as Boohoo warned on sales for the fourth time in the past 12 months, it reiterated its intention to become an online player comparable in scale to the biggest high street operators, such as H&M and Zara-owner Inditex.

“The opportunity is huge with half a billion potential customers across our key markets,” said chief executive John Lyttle.

He added that the price rises, along with the changes in demand patterns and higher rates of product returns, were “temporary, not structural, and will subside as the effects of the pandemic begin to ease”.

He also predicted that while cost pressures would persist into 2023, sales growth would eventually recover to around 20 per cent each year at profit margins of 10 per cent.

Analysts were more cautious. “The transition period seems to get longer at every outing,” said Panmure Gordon analyst Tony Shiret. “The sales have not sustained at the level they expected.”

Boohoo’s house broke Jefferies is forecasting relatively modest revenue growth of 11.6 per cent even for the year to February 2024.

Boohoo is not alone in having ambitions that contrast starkly with current reality. Its UK rival Asos held a series of investor meetings last year outlining how it would attack a market it put at £430bn.

It is aiming to increase annual sales from £3.9bn to £7bn “over the next three to four years” and lift profit margins from 2 per cent to “at least 8 per cent over the long term”.

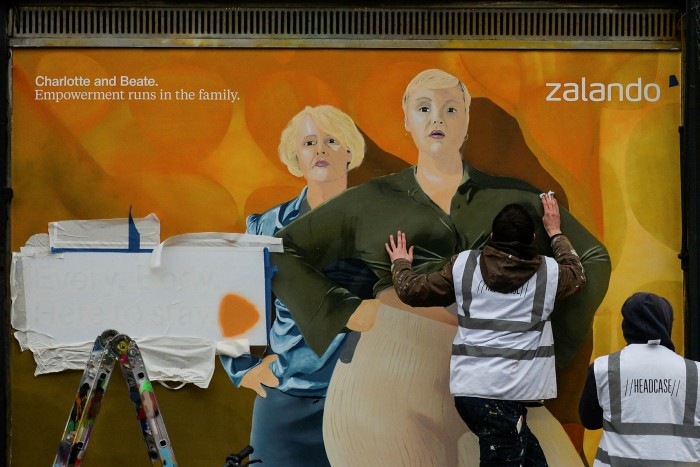

Similarly, Berlin-based Zalando, a larger company with more diverse operations, said this year had “started slowly” with lower confidence related to fears about inflation, but co-chief executive Robert Gentz was unperturbed.

Gentz was adamant that the company would not be rowing back on its near-term target of €30bn of sales across its platforms, or its long-term aim to serve 10 per cent of the European fashion market. “We are still at a very early stage of the journey,” he said while presenting results last week.

Action on costs

The online operators’ optimism stems in part from their confidence that they can mitigate the pressures. They are investing heavily in warehouse automation that will help offset rising labour costs. They have also moved production from places such as China and South Asia to Morocco and Turkey to shorten delivery times and reduce transport costs until freight rates return to more normal levels.

Asos’s chief operating officer Mat Dunn, who is running the company until a replacement for former chief executive Nick Beighton is found, said container lines were “making a lot of money and adding capacity again”. He was “even more optimistic” that air freight costs would come down as flight schedules returned to normal.

But not everyone is convinced costs will revert to pre-pandemic levels. Simon Irwin, an analyst at Credit Suisse, pointed out that the pandemic had accelerated the retirement of older, larger aircraft and their replacement with smaller jets.

“Even when we do get back to pre-pandemic flight numbers, there could be structurally less surplus [freight] capacity out there,” he said.

The retailers are also counting on consumers returning to work, going on holiday and attending parties and celebrations, events that typically drive clothing purchases but have suffered a big hit during the pandemic.

Lyttle said he believed Boohoo’s core audience of younger shoppers would be among the least affected by the coming squeeze on living standards.

But Dunn acknowledged the “vast majority” of ecommerce operators had not been tested in an inflationary environment. “The effect of [inflation] on disposable incomes is very hard to predict,” he said.

Room to grow

Online operators still have a lot to aim at despite their heady growth. Even in the UK, which offers the biggest opportunity for Boohoo and Asos, market shares are a long way behind the likes of Next, Primark or M&S.

Both are also targeting the US. “Its economy is growing faster . . . and consumers there display similar attitudes and behaviours to UK consumers,” said Jacqueline Windsor, a partner in PwC’s retail practice.

“But it is [geographically] much bigger and the density is much lower, so it is harder to serve in an efficient way,” she added, noting that even Amazon had found it hard to roll out next-day delivery nationwide.

Boohoo is constructing a warehouse in Pennsylvania to speed up deliveries and reduce dependence on costly and time-consuming air freight from the UK.

Asos opened a facility in Atlanta two years ago, although the company still made an operating loss in the US last year.

Dunn acknowledged “there were a lot of other things that Asos had to get right in the US”, but said that “you cannot compete at scale without your own warehouse”.

Strong economic growth in the US and lower levels of online penetration justified the significant investment needed, he added.

While Zalando’s ambitions are firmly anchored in Europe, the US is also among the markets targeted by Shein, a privately owned Chinese fast fashion group that has a ruthlessly efficient supply chain, rock-bottom prices and dispatches parcels direct from southern China, avoiding the customs duties that apply to large consignments.

Lyttle said the rapid growth of Shein demonstrated the size of the online opportunity.

But it is also a sign of how much more competitive online clothing is now than even a decade ago.

“You have the fast fashion players, the rollout of international fascias like Zara and H&M, the non-clothing retailers getting into clothing and then you have Amazon,” said PwC’s Windsor. The cost of customer acquisition in particular “is soaring” as a result.

This raises the risk that scale is achieved only by permanently sacrificing profitability. Operating margins across the sector have already been depressed by elevated costs, with Boohoo estimating that around £60mn was wiped off its profits in the year to February.

Rebuilding them will be a gradual process, with companies restricted on how much they can pass on rising costs to their value-conscious customers.

“We have got to remain competitive [on price],” said Lyttle.