Tianjin Saixiang’s “nanoknife” may be a form of precision surgery, but it is indicative of a broad trend that is reshaping China’s economic relationship with the rest of the world.

Made by a little-known Chinese company, it is designed to target prostate cancer without invasive surgery. Tianjin Saixiang was given the official imprimatur of “little giant” in 2020, meaning it qualifies for preferential treatment in return for helping China to climb the technology ladder.

According to an executive at the company, who declined to be named, this Chinese version of a cutting-edge treatment is part of a drive to reduce the need for imported medical technologies. The government “requires local hospitals to, where possible, replace foreign medical equipment with domestic ones,” says the executive. “That is a boon for us.”

This month, Xi Jinping gave a speech about the urgent need for breakthroughs in domestic technology in order to outcompete the west and bolster national security. The experience of Tianjin Saixiang is one small example of the scale of the Chinese leader’s ambition.

Under Xi — who appears all but certain to secure another term in power next month — China is seeking to become a state-led and self-sufficient techno-superpower that will no longer rely so much on the west.

The underlying objective, say analysts, is to build a “fortress China” — re-engineering the world’s second-largest economy so it can run on internal energies and, if the need arises, withstand a military conflict. While many in the US want to “decouple” their economy from China, Beijing wants to become less dependent on the west — and especially on its technology.

The strategy has several constituent parts and — if successful — will take several years to realise, the analysts say. In technology, the aim is to spur domestic innovation and localise strategic aspects of the supply chain. In energy, the objective is to boost the deployment of renewables and reduce reliance on seaborne oil and gas. In food, the path to greater self-reliance includes revitalising the local seed industry. In finance, the imperative is to counter the potential weaponisation of the US dollar.

Such changes represent a clear challenge for many multinational companies, some of which derive the lion’s share of their global growth from China’s market.

China’s self-sufficiency drive has been building for a number of years but has been accelerated since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the subsequent western sanctions on Moscow.

Chen Zhiwu, a professor of finance at the University of Hong Kong, says Chinese leaders understand military conflicts may be “hard to avoid” if Beijing wants to unify Taiwan with the mainland.

“The comprehensive economic sanctions against Russia after its invasion of Ukraine have only added urgency to [China] achieving self-sufficiency in technology, finance, food and energy,” Chen adds. “Self-sufficiency as a phrase has regained currency in the party’s publications.”

Steve Tsang, a professor at Soas, University of London, warns the construction of “fortress China” does not mean Beijing is about to seal itself off from the outside world. As the global economy’s top trading power and one of the biggest recipients of foreign direct investment, such a course would amount to economic self-harm.

“Instead, [Xi] is building a series of moving fortresses or forward bases to advance China’s place in the world,” says Tsang. “They are above all about making China an innovative power with technologies that others will look to China for sharing, making them dependent on China.”

Heavy gamble on tech

Many of the changes being signalled as China prepares to host the 20th National Congress of the Chinese Communist party in mid-October have been foreshadowed or in train for some time. But the party congress appears likely to reaffirm and accelerate the pace of several such developments.

Xi’s remarks as he presided this month over a meeting of the Central Commission for Comprehensively Deepening Reform, one of the party bodies he uses to rule China, set out a clear vision for technology.

The development of “core technologies” was not something that could be left up to the free market but had to be led by China’s government. “It is necessary to strengthen the centralised and unified leadership of the [. . .] Central Committee and establish an authoritative decision-making command system [for technology],” the CCTV broadcast quoted Xi as saying.

In an indication of the importance that Xi attaches to this agenda, he appears set to pack the new Central Committee, which comprises about 200 of the most senior officials in China, with technocrats, rather than career bureaucrats, according to an analysis by Damien Ma, managing director of Macro Polo, a US-based think-tank.

These tech-savvy officials will then be responsible for overseeing what amounts to a huge gamble. China is pouring unprecedented resources into fostering technological self-reliance, especially in strategic industries such as semiconductors, in the hope that such funding will lead to innovation and import substitution.

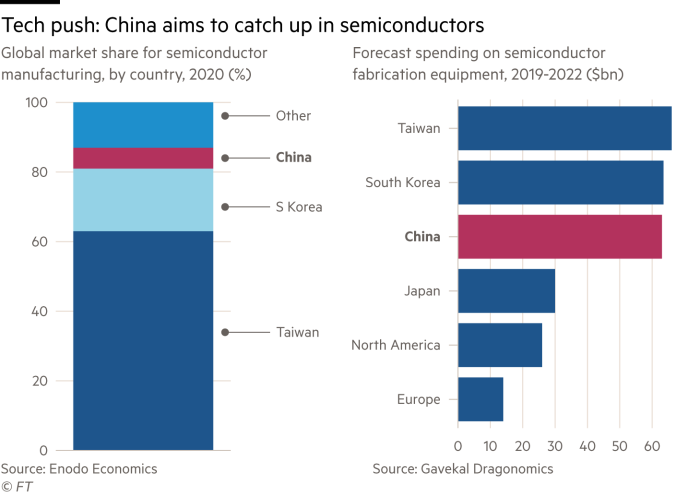

In total, well over $150bn has been pledged to spur progress in semiconductors. A report last year by Semiconductor Industry Association, a grouping of US chipmakers, found that $39bn has already been invested by China’s National Integrated Circuits Fund largely in new manufacturing projects.

In addition, more than 15 local governments have announced funds worth a total of $25bn dedicated to the support of Chinese semiconductor companies. A further $50bn has been earmarked in the form of “government grants, equity investments and low-interest loans”, the SIA report said.

By comparison, the US plan to dispense $50bn to support its own domestic semiconductor industry looks much more modest.

Semiconductors are generally considered the Achilles heel of China’s industry. In 2020, it imported a whopping $378bn of semiconductors, a supply chain vulnerability perpetuated by the fact that 95 per cent of installed indigenous Chinese capacity is dedicated to making trailing-edge technology, the SIA report said.

Nevertheless, some notable breakthroughs have occurred. It emerged this summer that SMIC, one of China’s leading chipmakers, has successfully made a 7 nanometre chip, putting it just one or two “generations” behind industry leaders such as TSMC in Taiwan and Samsung in South Korea.

Several analysts, however, say that notwithstanding such progress and the huge funds that China has dedicated to the development of its chip industry, goals of full semiconductor self-reliance are delusional. The industry is so complex and interconnected that no country can stand alone.

“Self-sufficiency is a fantasy for any country, even ones as large as the US or China, when it comes to chips,” says Dan Wang, technology analyst for Gavekal Dragonomics based in Shanghai.

A second strand to China’s efforts to attain technology self-sufficiency comes in two interrelated areas — the state’s selection of potential champions such as Tianjin Saixiang and government backing for a strenuous push into venture capital.

At a national meeting held this month in the eastern province of Jiangsu, China named 8,997 enterprises as “little giants”, putting them in line for tax breaks so they can help China compete with the US and other western powers.

Xi, in a letter to the meeting, said he hoped that such enterprises will “play a more important role in stabilising supply chains” — indicating his ambition that the “little giants” will help to indigenise China’s technology industry.

Support for such efforts can be found in Beijing’s assertion of increasing control over the country’s venture capital industry. In the past few years, China has overseen the establishment of more than 1,800 so-called government guidance funds, which have raised more than Rmb6tn ($900bn) to invest largely in tech sectors that Beijing deems “strategic”.

The funds’ salient feature is that they are mostly run by provincial and local governments or by state-owned enterprises. But here too analysts are sceptical over the long-term efficacy of Beijing’s attempts to “pick winners”.

An adviser to China’s government, who declined to be identified, says that several aspects of the “little giants” plan were flawed.

Companies had to be vetted by local governments in the first instance, opening up the potential for favouritism and corruption. At the same time, government officials can be poor assessors of a company’s prospects, especially when it involves technology that is hard to understand.

“The best way to identify . . . champions is to follow the rule of the survival of the fittest,” says the government adviser. “Any high-tech firm that grows big through competition should be viewed as a [candidate ‘little giant’]. It can’t be pre-determined by the government.”

Such concerns do not mean the “little giants” programme will fail in its objectives to foster greater self-reliance, but just that considerable waste and inefficiency may be built into the system.

Focus on renewables

At the intersection of geopolitics and technology lies another big vulnerability for China — the supply of energy. On a visit to an oilfield in northern China late last year, Xi made a clarion call that has echoed through the official media ever since.

“Our energy rice bowl must be held in our own hands,” he said.

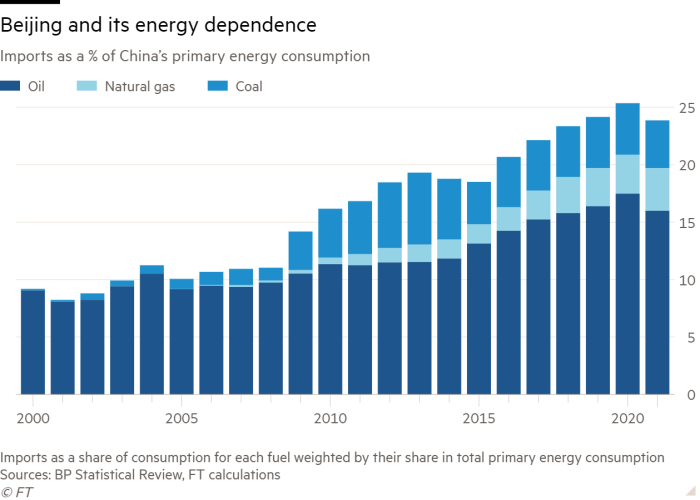

With the country’s current energy self-sufficiency rate at about 80 per cent, that leaves some 20 per cent of supply — mostly in the form of imported oil and gas — relatively vulnerable to external shocks. China is particularly concerned about shipping routes through “chokepoints” such as the Strait of Malacca, where US naval power remains supreme.

Michal Meidan, a director at the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies, says Beijing is adopting an increased focus on renewables such as solar and wind as part of the solution.

“China looks at the global geopolitical situation and assesses the vulnerabilities around supply chains,” says Meidan. “Enhancing and entrenching its dominant position in renewable manufacturing and supply chains as well as its deployment domestically makes a lot of sense.”

This creates a reliable impetus behind renewable future deployment that is already at world-leading levels. Analysts say China is on track to achieve early a national plan to source about 33 per cent of its power from renewables by 2025. But it will be many years before its vulnerabilities over seaborne oil and gas imports are shored up, they added.

Key food battlefront

A more intractable dependency on the outside world comes in agriculture.

China’s food security has plummeted over the past three decades as its population has grown and agricultural land usage has shifted from grains to more lucrative crops. In 2021, only 33 per cent of the country’s total demand for the three main food oils — soyabean oil, peanut oil and rapeseed oil — was satisfied by domestic production, down from more than 100 per cent in the early 1990s.

Although successive Chinese leaders have stressed the vital importance of food security for years, analysts believe the language and tone has hardened under Xi.

That has been especially the case since the trade war rhetoric unleashed by the US under Donald Trump and the 2019 publication of the food security white paper by China’s State Council. Food security and national security have since been clearly conflated by senior leaders and the goal of staple food self-sufficiency increasingly described in similar terms to other “fortress China” ambitions.

Key policies on grain output focus on the need for ever greater yields, as well as greater protection of arable land, more efficient water use and other big water-saving projects. China aims to maintain its self-sufficiency in major grains, which reached over 95 per cent in 2019.

But the most important policy, according to analyst Trina Chen at Goldman Sachs, is the seed industry revitalisation plan, which Xi first promoted in 2021 and which urges greater efforts to achieve self-reliance.

The really key inflection point that will show food production coming under the “fortress China” bracket will be the introduction of the first generation of GM seeds in China — a shift that has been strongly resisted but which analysts now see as inevitable. (China only uses GM cotton at this point.) The attitude has shifted since the Chinese acquisition of Syngenta, the Swiss agritech group whose large business portfolio includes seeds and the development of domestic GM producers.

The dollar as a weapon

“Fortress China” calculations can also be seen in China’s attitude toward the dominance of the dollar. For Beijing, one of the most alarming features of the western sanctions on Russia was the exclusion of some of its financial institutions from Swift, a global messaging system that is central to international settlement.

Chinese officials have long warned of such a scenario. “When Americans . . . frequently use sanctions and over-emphasise the interests of the US while ignoring its international responsibilities, more and more nations hope to reduce their reliance on the dollar,” wrote Zhou Chengjun, director of the People’s Bank of China’s Institute of Finance, in May last year.

Vulnerability to this type of sanction arises because about three-quarters of China’s trade is invoiced in dollars — which means it relies on access to Swift.

Beijing’s solution can only be in the long term. Its efforts to “internationalise” the renminbi, its currency, have met with limited success so far. Similarly, efforts to promote a “digital renminbi” — which dispenses with the need to use platforms such as Swift’s — have been slow.

“Over the short run, Beijing has been at pains not to fall foul of western sanctions imposed on Russia over its invasion of Ukraine, but also its focus on decoupling from the dollar has sharpened,” says Diana Choyleva, chief economist at Enodo Economics in London.

China’s emphasis on self-reliance has been a long time coming. From about 2015 onwards, Xi’s administration placed increasing emphasis on self-reliance in industrial supply chains. That intensified with last year’s launch of China’s 14th “Five Year Plan” and the introduction of a policy called “dual circulation” — which stressed China’s need to rely on internal dynamism.

Since then, a rising tide of US sanctions on Chinese companies, geopolitical divisions flowing from China’s support for Russia in the war in Ukraine and a surge in tensions over Taiwan have reinforced the trends underpinning “fortress China”.

Such a heavy emphasis on domestic technology poses a significant risk to those multinational companies focused on supplying the Chinese market. According to one senior Asia banker, there is currently a massive disconnect in the boardrooms of western companies between their enthusiasm for the growth potential of their businesses in China and their silence on the geopolitical debate that is shaping the environment they have to operate in.

“A lot of the western companies blame themselves for not speaking up and making it clear what they think the business relationship between China and the west should look like,” says the banker. “But at the same time they feel pretty unable to do anything about that, because with things the way they are, what is the upside of being the company that speaks up?”

However, some analysts believe that for all the political slogans, there are still important limitations on the scope of the “fortress China” plans.

Yu Jie, a senior research fellow at Chatham House, a UK think-tank, argues that China cannot afford to completely isolate itself from the world due to its export-oriented structure. As a result, Beijing is likely to adopt a hybrid approach depending on the industry.

“Sectors with strategic importance and everyday necessities for the population will be treated as matters of national security,” says Yu, “whereas sectors that require foreign capital and manpower will remain open and interconnected to the world.”