A recent Sunday New York Times had an insert where the top half of the first page says in bid letters “We Believe in Science.” The rest of the insert is about a company’s line of beauty products. I’m not competent to judge either their products (beauty eludes me) or the science behind them, but it makes you wonder if we’ve reached ‘peak science’ kind of like Joe Kennedy supposedly sold his stock holdings shortly before the 1929 market crash because he heard a shoe-shine boy giving stock tips.

Scientific illiteracy is regularly bemoaned in this country (and abroad), with the covid pandemic highlighting skepticism about ‘expert’ opinion and any number of people describing doing ‘research’ on the vaccines, by which they mean ‘a google search where I ignore anything I don’t like.’ The ridiculousness of this is exemplified by Aaron Rodgers saying he gets his vaccine advice from Joe Rogan, which is interesting since Joe Rogan says he’s not a doctor but a (colorful language here) moron. Somehow, Rodgers seems to have missed that particular pronouncement.

Searching the internet can be useful; I do it all the time. But if you want to develop some skepticism, type your name into Google and click ‘images.’ You will be surprised, and probably not pleasantly. (Unless your name is Tom Cruise.) The point isn’t that searching the internet is bad, but that bad searches yield bad results.

Last summer, the Wall Street Journal featured op-eds by Neil DeGrasse Tyson speaking in favor of the scientific process and Gov. Ron DeSantis bemoaning the influence of the elites, which might seem a strange juxtaposition. However, anyone who follows public policy and scientific debates will know that there is often a disconnect between what scientists believe and what the elites embrace. (I use both terms loosely.)

First and foremost, it is quite easy to find a scientist somewhere who will support the craziest notions imaginable. Recall the Harvard professor who thought huge numbers of people were victims of alien abductions. Similarly, promoters of the use of horse dewormer Ivermectin are able to find some research, albeit scanty, to support their arguments—while ignoring the huge body of research behind vaccines.

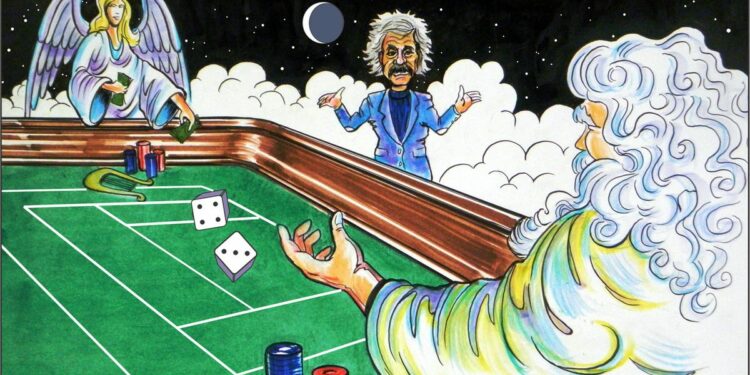

The point is that simply being able to cite one article or seemingly learned opinion is far from hard and fast proof. Recall that Einstein famously disputed the theory of quantum mechanics, saying “God does not play dice.” Most physicists would disagree with that now. Of course, Einstein also (less famously) said, “Everyone is stupid about something,” a sentiment more scientists need to embrace.

I have known many thoughtful scientists who had opinions but were open-minded: the late peak oil advocate Ken Deffeyes would actually suggest to people that they listen to opposing opinions, and recommended they contact me on a couple of occasions. But there are other scientists who think that having a degree in science somehow made them unbiased and objective, even when they are disagreeing with the evidence. And there have been far too many times when scientists would argue that their critics should not be given a public platform, including on climate change.

Everyone has heard stories of scientific theories that were roundly denounced before becoming accepted as legitimate, such as plate tectonics, bacteria causing ulcers, and so forth. But those cases are a reason to be skeptical of, but not reject, scientific consensus. Of greater concern to me at least is the embrace of theories that are not supported by evidence or only thinly so. Michael Bloomberg wanted to control New Yorkers salt intake even though the medical research didn’t support such a move. A belief that sugar didn’t cause obesity but fats did became just as widely believed but was similarly based on no evidence. Anti-vaxxers sometimes argue that the toxicity of mercury is scientific fact, while ignoring the reality that the earlier use was of mercury compounds, not the element, which are not toxic, in vaccines.

And it’s always interesting to see the people who insist that mistakes such as the scientific embrace of eugenics or the aggressive defense of the (fake) Piltdown Man fossil are things of the distant past, and that scientists today are beyond such errors. Would that it were so. That doesn’t mean one should reject the views of scientists, but merely treat them with a degree of skepticism, especially when filtered through either social media or mainstream media.

So, what to believe about energy and climate? Just as you shouldn’t use horse dewormer because of a Facebook post, you shouldn’t believe a teenager who asserts they are following ‘the science.’ Much of what is said about climate change and energy policy is both simplistic and misleading, often completely false in fact. This is true of both sides of the debate. Studies that predict, for example, extinction of a particular species or long-term weather in a given region should be recognized as not concrete facts but suggestive evidence, just as few people react to every pronouncement about minor effects of given diets. (Tomato eaters have three percent more ear lobe cancer!)

If you are writing energy legislation or planning your company’s investment strategy you are hopefully not listening to one or two advocates on either side of the debate, and certainly not to podcasts of comedians. That is my wish, at least, but admittedly I anticipate disappointment.