Good morning. I have Covid, and that’s a drag, but my symptoms are mild. They include a slight sore throat and annoying my family even more than usual. Hope my luck holds. Netflix’s luck has not. I try to tease out the meaning of its very bad day below. Email me your own thoughts: robert.armstrong@ft.com.

Netflix

I used to write a lot of columns about how expensive tech stocks such as Amazon or Facebook or Netflix were, and how competition would soon lead to slower growth, and investors were taking terrible risks, and so on. These were very bad, stupid columns, which have been proven hilariously wrong by subsequent events. Many of these columns are on the FT website still. I am not going to provide links; if you want to mock me, do your own research.

Now I have internalised a lot more stuff about zero marginal costs, first- mover advantages, natural monopolies, W. Brian Arthur, limp antitrust enforcement, cost of capital differentials, and so on. Now I think huge tech companies are smart, relatively low-risk things to invest in. What helped me internalise all this stuff was that Amazon and Facebook and Netflix kick exponentially more ass with each passing year.

Netflix’s first-quarter results are the only example I can think of where the exponential ass-kicking of one of these big tech companies came screeching to a halt. Yes, Facebook is wilting, but the suddenness of the Netflix slowdown is something new. Just one example: between the second and third quarters of last year, Netflix added a million new subscribers (a 4 per cent gain in three months!). In this year’s second quarter, the company expects to lose 2 million subscribers.

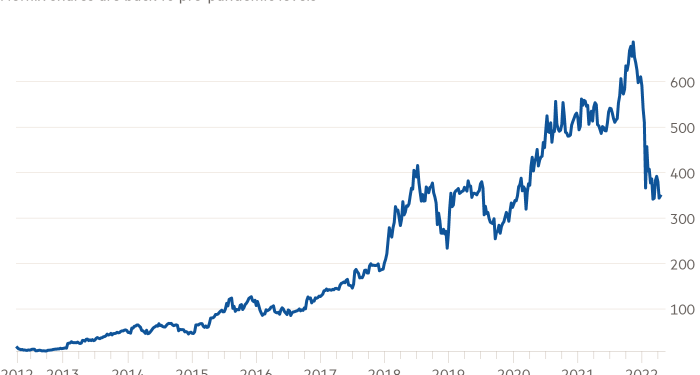

The stock fell 35 per cent on Wednesday, and has now lost nearly 70 per cent of its value since October.

This is not a vindication of my former views. If you had bought Netflix a decade ago, when I was bitching about it in the Lex column, you would still be up 28-fold. But it is worth pointing out at wild moments such as this that most of the time markets do a pretty good job of pricing things. And this looks like one of those times. I don’t think this mess was easy to see coming, and I don’t think the market overreacted to the news. Despite the huge move, the price on Tuesday was fair, given the information that we had, and the price now is fair, given what we have learned. And that may tell us something about the current moment.

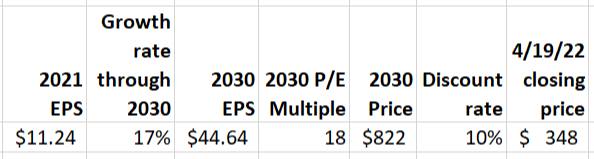

Let me try to illustrate this with the following idiotically simple analytic device:

Moving from left to right, we start with Netflix’s earnings per share in 2021. Next up is Wall Street’s consensus view (as of Tuesday) about the compound annual growth rate of Netflix’s earnings through 2030 (data from Bloomberg). That gives us the third cell, the company’s expected 2030 earnings. Let’s put a price earnings multiple on that that sounds reasonable: 18 is much lower than Netflix’s current multiple, but that makes sense. The company’s prospective is almost certain to get lower with time, and lower-growth companies merit lower multiples.

The 2030 earnings and the multiple render the estimated end of 2030 price. Last question: at what rate shall we discount that future price back to the present? Ten per cent sounds OK. It is a higher cost of capital than would be implied by what the company would currently pay for new equity or debt funding, but capital is unusually cheap now. Using that discount rate you get a price of $348 — that is, Tuesday’s closing price.

Of course I reverse engineered both the multiple and the discount rate to get the number I wanted, but the point is all these figures are eminently reasonable. Is 17 per cent annual earnings growth wildly optimistic? Well, in the last four years (2018-2021) Netflix’s earnings growth has been 114, 54, 47 and 85 per cent respectively. The company has been consistently widening margins, raising prices and adding subscribers. Ambitious maybe, crazy no.

Yes, everyone knows that streaming competition is intense as every entertainment company throws money at it — but that’s why the stock had already been cut in half in the six months before this week’s announcement.

Then came the news. Subscriber numbers are suddenly expected to fall. The outlook for margin expansion (three percentage points a year, exactly what they had been delivering) was put on hold for now. Suddenly, the growth strategy is not taking share from linear TV, but stopping password-sharing and launching an ad-sponsored version of the service. This is from the quarterly letter to shareholders:

Our relatively high household penetration — when including the large number of households sharing accounts — combined with competition, is creating revenue growth headwinds . . .

COVID clouded the picture by significantly increasing our growth in 2020, leading us to believe that most of our slowing growth in 2021 was due to the COVID pull forward.

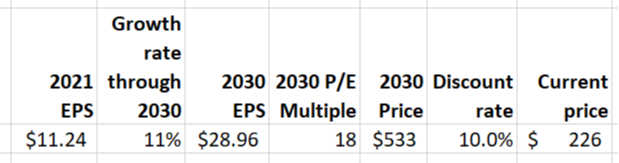

What do we think will be the medium-to-long-term growth rate of Netflix earnings now? Not 17 per cent, surely. Lets try 11 per cent instead. That’s a little less than the company thinks it can do (it’s current “goal” is “to sustain double digit revenue growth, increase operating income even faster”) but seems reasonable to me. There is loads of leverage in Netflix’s model. If it can squeeze even a few points of revenue growth out of pricing and new markets, double-digit earnings growth should be within reach. Voila:

The change in growth outlook means stock loses a third of its value . . . just as it did on Wednesday. Reverse engineering again but, I think, reasonable. Perhaps the price damage could have done worse. One has to be more uncertain, now, about the future of this business, which probably justifies a higher discount rate, along with the lower growth estimate.

To sum up: this was one of the biggest earnings surprises and the biggest one-day sell-offs I have ever seen that involved a big company. And it was neither predictable nor overdone. The notion that it was obvious beforehand that Netflix’s valuation was crazy or that its business model was clearly in trouble — which we heard a lot of yesterday and will hear a lot of in days to come — is hindsight masquerading as foresight.

I propose the Netflix smash-up is evidence that, because of the distortions of Covid-19 (and inflation, too) this is a moment of genuinely high uncertainty for investors in general. This is a dangerous claim to make, because all moments feel uncertain to investors; doubt is the water we swim in. But remember: Netflix’s management team said just three months ago that they would add 2.5 million subscribers in the first quarter. They missed that target, on an adjusted basis, by 2 million. Management did not set the target lightly. This is a team that has learned the hard way that overpromising is the best way to piss off Wall Street. They were blindsided by their own business.

If I’m right about this, this is a moment for conservative portfolio allocations and avoiding high valuations. Don’t pay up for what you can’t reasonably forecast.

One good read

Always read Thomas Edsall.