At the heart of the greater Brexit narrative has always lurked a deep tension between the parochial and the global.

The vision of buccaneering “global Britain” competed in voters’ minds with the promise of “taking back control” — not just narrow political control from Brussels, but also from a more diffuse range of forces of globalisation from financial elites, Big Tech and the fallout from the gig economy and the fourth industrial revolution.

Until Brexit actually happened, those two contradictory narratives often happily coexisted on the stump side by side — but two recent stories have pointed to where the balance of decision making tends to come down on the parochial side of the political ledger.

The first is the furore that is being caused in the tech industry by the Online Safety Bill, which uses Brexit freedoms to fundamentally change the way in which online platforms are regulated.

Under the EU’s e-Commerce Directive, online platforms were not legally liable for what appeared on their sites, but did have a legal duty to take illegal and harmful material down, once it was identified. However, EU member states were explicitly prohibited from imposing a general obligation on platform owners to pre-monitor content for fear that it would amount to snooping, breaching the freedom of speech rights of their users.

Now that the UK is no longer subject to EU directives, the Home Office and the culture department are proposing changes to internet regulation that would, in certain circumstances, make the duty to remove harmful content proactive, not reactive.

Companies, monitored by a new watchdog in Ofcom, will be required to actively monitor content on their sites. Failure to prevent harms could be met with fines of up to 10 per cent of global revenue, with liability placed directly on senior managers.

The tech industry is arguing that this new approach, which in some senses turns the existing system of content regulation on its head, will put the UK’s burgeoning tech industry at “serious risk”.

This report by The Coalition for a Digital Economy (Coadec), an advocacy group for UK tech start-ups, claims the changes will heap compliance costs of £2.5bn a year on a sector that attracted £30bn in direct investment in 2021.

Brexiters and ministers frequently like to boast about the UK’s tech “unicorns”, citing the industry as an example of where post-Brexit Britain can prosper on its way to becoming a “science superpower”, creating a vortex sucking in global talent and investment compared with the laggardly EU.

And yet tech industry lobby groups are fuming. Coadec says the reforms will make the UK “a global outlier” in how online liability is enforced, warning this will turn the UK into “a significantly less attractive place to start, grow and maintain a tech business”.

TechUK, the main industry lobby group, has been equally forthright. Antony Walker, the group’s deputy chief executive, said the bill went against international legal norms “undermining the perception of the UK as an open digital economy”.

He added — in the best traditions of Brexit relations between industry and the Johnson government: “None of these proposals have been consulted on with industry, which is a poor way to draft legislation at this late stage.”

Industry executives also point out that, aside from denting the UK’s credibility as a tech destination, judging online harms, particularly ones that are “legal but harmful” is necessarily subjective and deciding what is or isn’t will quickly become deeply political.

It’s not surprising, perhaps, that the global tech industry will resist onerous new regulations. Nor, on the parochial side of the ledger, that introducing greater controls on “platforms”, particularly when they protect children, will be politically popular.

Traditional publishers, including some Conservative-supporting newspapers, have also long wanted a way to clip the wings of the tech platforms, which they see eroding their advertising revenues and cannibalising content.

There is clearly a legitimate argument to be had here over internet regulation, but it is interesting to note on which side this government — which so often likes to champion the concept of global Britain — is coming down on.

This may be smart local politics in the short term, but it remains to be seen what it does for the UK’s investment and productivity in the longer term.

That is also the case for the decision to shelve the “Oxford-Cambridge Arc”, a George Osborne-era plan to create a UK Silicon Valley that links the UK’s two great universities through the logistics and manufacturing hub of Milton Keynes.

The decision by Michael Gove to prioritise “levelling-up” spending in other parts of the UK has gone down very badly with the medtech industry that delivered the Covid-19 vaccines and is also often cited as an example of post-Brexit Britain’s global ambitions.

Some 17 affected companies wrote to Rishi Sunak, the chancellor, warning that the failure to invest further in one of the UK’s most dynamic and productive regions will reduce the attractiveness of the region to investors.

Indeed, they warn that companies are already shifting to places such as Boston in the US where there is vastly more laboratory capacity being built than in the UK.

“In short, without direct HMG intervention to plan appropriately for the future we will deliver the worst of both worlds — losing out to international competitors combined with the steady deterioration of the cities as high-growth business clusters,” they wrote.

Again, there is always an argument to be had about where investment is best laid, but the combination of the “levelling-up” agenda and decision to go soft on UK planning reforms following the Tory defeat at the Chesham and Amersham by-election last June has led — for now at least — to the parochial rather than international and industrial side winning out.

Do you work in an industry that has been affected by the UK’s departure from the EU single market and customs union? If so, how is the change hurting — or even benefiting — you and your business? Please keep your feedback coming to brexitbrief@ft.com.

Brexit in numbers

As a counter-narrative to all of the above, there is one area where the government’s Global Britain narrative is being put into practice — skilled immigration.

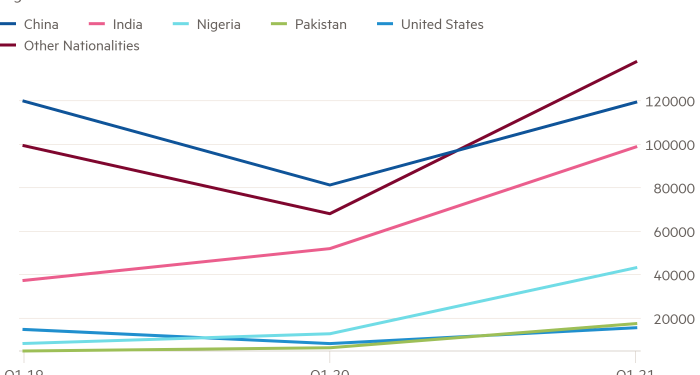

An analysis of the first full year of post-Brexit immigration data by Jonathan Portes at King’s College London shows that the decision to prioritise EU and non-EU immigration equally has led to significant shifts in the balance of immigration for students and skilled workers.

One area that has had a big impact is the new Health and Care Visa (HCV), of which about 65,000 were issued in 2021 as the NHS sought to address its staffing crisis, drawing in workers from countries such as the Philippines and Pakistan.

The introduction of the Work Route, which offers international students the ability to stay in the UK and work for two years after they graduate, has also proved attractive, with 12,500 visas issued so far.

Portes, in a blog for the UK in a Changing Europe think-tank, says he expects the numbers to grow. It will also be fascinating to see, over time, how many of these workers shift on to full skilled worker visas — a potential ‘brain gain’ for the UK.

The numbers for international student visas, as the chart shows, are also striking, with a huge jump in Indian, Nigerian and Pakistani students coming to study in the UK, while Chinese and American numbers remained roughly static.

While some EU companies can be heard grumbling about the difficulty in obtaining skilled worker visas, now that the UK no longer allows free movement, the reality is that they find themselves having to play on an internationally level playing field.

That’s inconvenient compared with what went before, but fundamentally, says Portes, what the data show is that the new system is working, with visas being processed reasonably and the IT and application systems working too — confounding many pessimistic predictions of the UK Home Office, including his own.

“My expectations were considerably more pessimistic, and I’m glad to say I was wrong,” he writes.

And, finally, three unmissable Brexit stories

There has been a lot of debate this week about the impact the Ukraine war will have on the EU-UK security relationship. Robert Shrimsley writes that Russia’s invasion of its western neighbour ends the lofty dreams held by some Tories of a tilt to the Indo-Pacific. “The crisis hammers home the fact that the UK cannot escape its geography,” he argues.

The war in Ukraine is causing huge disruption to the global, but especially, the European energy market. Nevertheless, argues Martin Sandbu compellingly in the latest edition of his Free Lunch newsletter, there is no better time for the EU to go “cold turkey” on Russian oil and gas imports. “The west, and especially the EU, should expand sanctions to the energy trade, and do so now”, he writes.

The World Economic Forum estimated that the number of bytes in the digital universe in 2020 was 40 times greater than the number of stars in the observable universe. To govern the way all that data is stored and transferred the UK and EU adopted GDPR in 2018. But now the UK is planning a mass overhaul of its data regime which, critics say, could end the free flow of information between Britain and the EU.