Amid new pandemic restrictions, employees depend on such hearsay as “tumbleweed is rolling” to gauge how empty their offices are. Employers have accurate but private turnstile data. Investors are mostly stuck with out-of-date reports from beleaguered property companies. These inevitably hype up any signs of a “Great Return”.

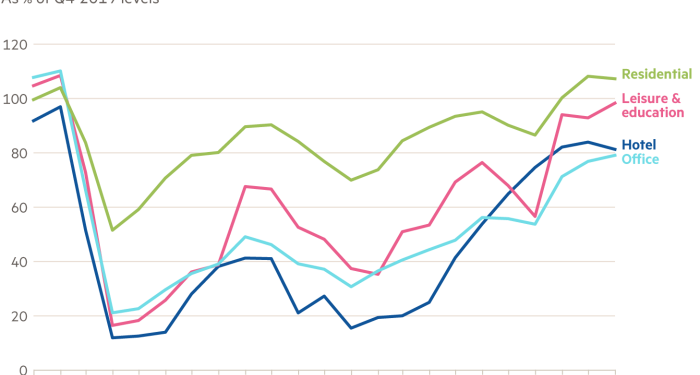

Last week, Finnish engineer Kone published harder numbers gleaned from its lifts in offices all over Europe. These underlined the growing power of unconventional data to reveal behavioural trends — and to create potential opportunities for investors.

In London, for example, average trips per lift of 13,000 monthly in 2019 crashed to 2,500 last year. Since then, lift trips have quite literally been “going up”. They rallied to two-thirds of pandemic levels last month.

Most complex machines now contain sensors, microchips and web connections. This “internet of things” generates huge volumes of data for algorithms to sift.

Kone’s motivation is primarily to make its lifts work better and optimise foot traffic through buildings. This is a noble aim. Lex, in a column devoted to asset allocation, has, for example, long dreamt of smart signboards in theatres to minimise queues for loos during the interval.

Equally, accurate footfall data could show investors that a development on which a chief executive has staked their career is an abject failure. The caveat is that correlation does not prove causation. Investors who tried to deduce sales trends at Walmart from satellite photos of its car parks found that many motorists were visiting rival stores.

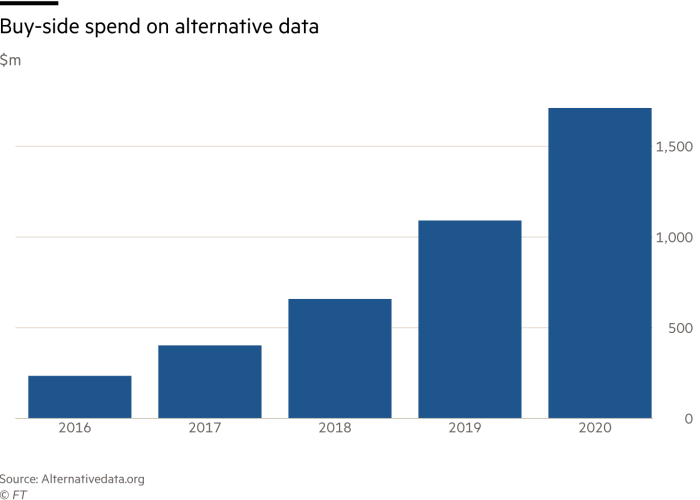

IoT devices at present make up a small part of the sea of data beyond old-fashioned company accounts and stock price moves. Social media, mobile devices and ecommerce portals are all richer veins. They will become even more valuable as computers get better at reading text generated by humans.

New York-based YipitData, a specialist in alternative data collection and analysis, recently received $475m of private equity investment from Carlyle. The company sells products and services within industries but also to third parties in the financial sector.

Banks and their ilk are the biggest buyers of big data analysis. Businesses ranging from high-frequency traders to traditional insurance groups are all striving for an edge.

The market for big data, estimated at $7.6bn in 2011 is expected to grow to more than $100bn by 2027, according to Statista. We can all expect to be tracked, weighed, analysed and cajoled into handing over more information about ourselves.

Big data raises big questions about data privacy. If you think you are alone in that lift with your colleague gossiping about the boss, think again. Wherever you are, sensors are following you.

The Lex team is interested in hearing more from readers. Please tell us what you think of the opportunities and challenges created by big data in the comments section below.