The writer is founder of Sifted, an FT-backed site for European start-ups

On the peanut butter spectrum, artificial intelligence is rapidly moving from smooth to crunchy.

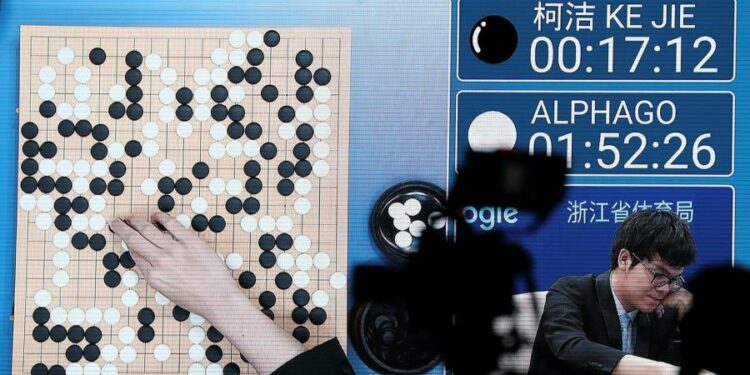

Many of the technology’s most high-profile uses to date have been in the fields of games playing, image recognition and language generation, which we can all recognise. AlphaGo, developed by Google DeepMind, beats the strongest players in the ancient game of Go. Generative adversarial networks create deepfake videos substituting Burt Reynolds’ face for that of Sean Connery in a James Bond film. Open AI’s GPT-3 program can write an unnervingly authentic poem in the style of Emily Dickinson.

But AI is increasingly being used in many more specific, invisible and productive ways across industry and in the hard sciences. Perhaps more narrowly defined in most cases as machine learning, AI has become a powerful technological tool that is being used to optimise search engines, accelerate drug discovery, invent new materials, improve weather prediction and deepen our understanding of mathematics, biology, chemistry and physics. That diffusion of AI into almost every corner of the economy and society is going to profoundly affect us all.

A new report from Stanford University highlights the “industrialisation” of AI as the once-speculative technology has become more affordable, higher performing and mainstream. Global private investment in AI more than doubled to $93.5bn in 2021 compared with the previous year, according to Stanford’s latest AI index. The number of AI patents has increased 30-fold since 2015. While commodity, food and energy prices have been soaring, the median price of a robotic arm has fallen by 46.2 per cent over the past five years.

One of the most promising uses of AI is to accelerate research in other fields, fuelling innovation. Google DeepMind, which used neural networks to develop AlphaGo, has applied similar ML techniques to mathematical modelling, protein folding, material science and nuclear physics. Its latest application has been helping to control superheated plasma inside fusion reactors, which may one day offer a source of cheap, green energy.

“ML is definitely a great accelerant of research and enables us to do things that we could not do before,” says Pushmeet Kohli, DeepMind’s head of research. As an example, DeepMind cites its AlphaFold database of protein structures that has been accessed by more than 350,000 users in over 190 countries.

Other researchers are applying AI to quantum computing, which may one day trigger a further leap in technological capability. QuantrolOx, an Anglo-Finnish AI start-up, is using ML to “tune” qubits, or quantum bits, making early-stage quantum computers more stable. The use of ML systems in research labs in future is going to become as ubiquitous as computers today, predicts Andrew Briggs, emeritus professor of nanomaterials at Oxford university and co-founder of QuantrolOx. “I cannot think of an area of the hard sciences where ML cannot be applied,” he says.

However, one of the unnerving aspects of this AI transformation is the growing imbalance of knowledge and power between the private and public sectors. In some areas, private sector research is being fed back into the scientific community, as is the case with AlphaFold. But increasingly, it is private companies, rather than universities, that are becoming the centres of leading-edge AI research and are reaping almost all of the gains.

In recent years, technology companies have been snapping up university AI experts, if not whole departments. The Stanford study found that in North America the private sector hired 60 per cent of newly minted PhD students in AI last year while 24 per cent remained in academia. A decade ago, that split was roughly equal. “A much higher proportion of AI research at the frontiers is being dominated by industry,” says Jack Clark, co-author of the Stanford report. Naturally enough, he suggests, those companies prioritise narrow financial return over broader societal benefit.

The promise is that the industrialisation of AI will stimulate a new burst of innovation and productivity growth. The concern is that it will lead to lopsided development in which universities, civil society and governments lack the necessary knowledge to keep up with the latest breakthroughs. That is all the more reason why we need to retain expertise within academia and the public sector and develop common infrastructure, such as national research clouds, that will broaden access to AI. Unscrutinised and unchecked corporate power, whether in energy, finance or technology, is never a good idea.