In 2013, Carl Icahn took on the biggest company in the world. The activist built a 1 per cent stake in Apple, slammed its “ridiculous” cash hoarding, demanded a $150bn share buyback and threatened to force a shareholder vote.

He was taken seriously, by the market and the company. Apple’s stock rose when he bought shares and fell when he eventually sold. Chief executive Tim Cook felt obliged to have dinner with the veteran corporate raider and listen to his views.

Not all of these were on the money. Icahn was convinced that Apple would produce a television set by 2016 and a car by 2020. He was oddly specific: the TVs would be 55 and 65 inches. No such products have emerged.

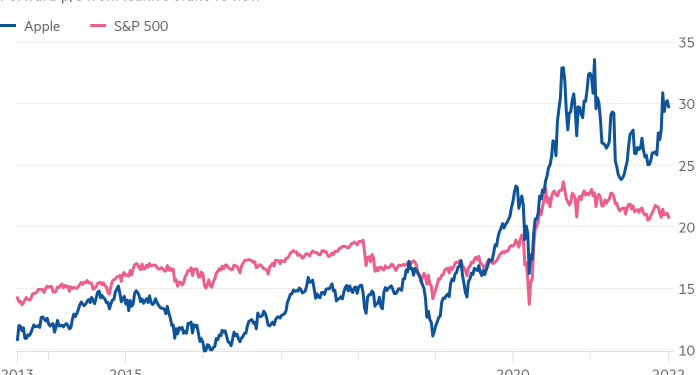

But his primary point was bang on: the stock was ludicrously undervalued, trading at a significant discount to the S&P 500 despite Apple’s record of consistent growth and strong profits.

That is no longer the case. Apple was worth a mere $424bn when Icahn revealed his initial $1bn position. Its market capitalisation crossed $3tn this week and now trades at a big premium to the index.

Icahn has not reaped the benefit. Citing concerns about Apple’s prospects in China, he exited in 2016. He made $2bn on the trade but would have made tens of billions had he held on.

Part of the reason for the uplift is that Cook successfully shifted the revenue mix from hardware like iPhones towards software and services, which are more reliable and profitable.

But he also released cash. Although Icahn’s buyback prescription was not followed to the letter, Apple has hugely increased shareholder payouts. The company started paying dividends in 2012. It now returns more than $100bn a year to shareholders.

Apple founder Steve Jobs had jealously guarded the world’s largest corporate piggy bank, scarred by near-bankruptcy in the 1990s. But breaking into it has helped drive the company’s valuation higher, providing a higher class of protection.

Any activists trying to follow Icahn today find the ante raised. Buying a 1 per cent stake looks beyond reach, never mind amassing enough shares to really muscle the board.

But other things have changed since 2013. Size is less important if an activist has either a solid record or a trendy theme. Activists at Engine No 1 had a tiny stake in ExxonMobil but won over larger shareholders to force a change in the company’s emissions policy.

Strangely enough, Apple looks more vulnerable to activist pressure than it has since Icahn. A new breed of activists is buying tiny stakes and using them to push shareholder resolutions. A newly sympathetic Securities and Exchange Commission is facilitating this, allowing resolutions to go forward when, previously, officials might have helped the company strike them from the ballot.

On Thursday, Apple published proposals that will be put to a vote in March. They include six shareholder motions that range from banning gagging clauses for employees who suffer discrimination to increasing transparency on how the company removes apps from its App Store.

These subjects pose a much more complex challenge than the cash demands of yore. Worse for Apple: its biggest shareholders can no longer be relied on to toe the corporate line. It is enough to make Tim Cook yearn for dinner with Carl Icahn.