The workers leaving an Amazon warehouse in Bessemer, Alabama, seemed more interested in getting into their cars after their 10-hour shifts rather than engaging with the gaggle of trade union reps stationed outside.

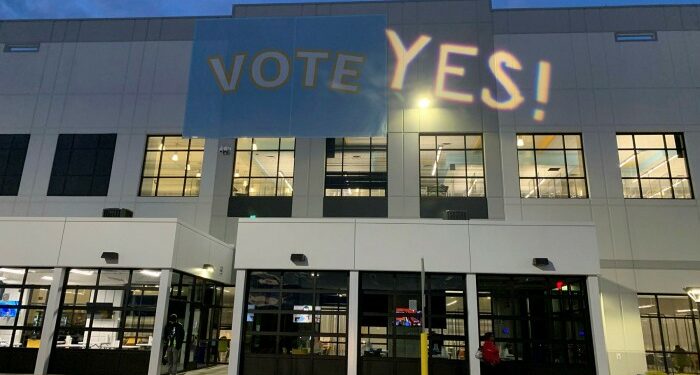

Those who glanced back at the 850,000 sq ft plant, known as BHM1, would have seen the union had projected “YES!” next to Amazon’s own “VOTE” banner.

The messages sum up an important choice: should the Bessemer plant become the first unionised Amazon facility in the US?

“God didn’t bring us this far to leave us,” said Jennifer Bates, an Amazon worker at the plant, and one of the leaders of a campaign for her colleagues to join the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union (RWDSU). “We’re going to continue the task until it’s complete.”

Amazon maintains its workers are happy. In a previous vote in Bessemer, last April, workers voted by 1,798 to 738 against unionisation. But the contest is being rerun after the US National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) ruled Amazon’s installation of a special voting mailbox at the facility risked making employees feel surveilled. Postal ballots are due to be counted next week.

If the more than 6,000 workers eligible vote yes, it would be a disaster for a $1.4tn company that has grown to become the second-biggest employer in the US, after Walmart. Amazon has added 800,000 to its global headcount since the start of the pandemic.

Independent observers do not rate the union’s chances of overturning the election result. “When workers organise, we see the kinds of campaigns that Amazon has carried out in Bessemer, which are designed to instil fear,” said Ken Jacobs, chair of the Center for Labor Research and Education at University of California in Berkeley. “By the time you rerun an election all the damage has been done, the well’s already been poisoned,” he added.

Amazon has denied it deploys unfair tactics: “It’s our employees’ choice whether or not to join a union. It always has been.”

Over its 28-year existence, Amazon has an unbeaten record in squashing unionisation efforts in the US. Until last year, no facility had ever managed to even hold a vote, let alone muster a victory. The stakes for Amazon are even higher now than at the time of the last Bessemer vote, as labour shortages and supply chain crunches led to $4bn in additional costs in the last quarter.

In 2022, Amazon faces future challenges, with workers at a facility in New York set to begin voting in person on unionisation this week, while another will vote in April. Staff at two other locations in New York, and one in Maryland, have recently staged brief walkouts demanding pay rises. The Teamsters union has lobbied officials in San Francisco to allow workers to organise at an as-yet unopened Amazon plant in the city.

Around Bessemer, a majority black and working-class city whose glory days of steelmaking and manufacturing were crippled by globalisation, little red signs supporting the RWDSU can be seen on front lawns.

“The man that owns that company has money and he needs to do much better,” said one resident, Carolyn Wilson, referring to Amazon’s billionaire founder, Jeff Bezos.

The starting wage at Bessemer is $15.80 an hour, above the US minimum wage but short of what many economists consider a living wage. The union said it would demand higher pay, and push back on some of the surveillance used by Amazon to ensure extremely high rates of productivity.

That includes “Time Off Task” — a system that logs a worker’s time away from their duties. Many have complained that it can unfairly punish workers for bathroom breaks, or even times when there is no work to actually complete. Amazon has disputed these characterisations, though its workplace systems are known to underpin the company’s efficiency and speed.

“If Amazon loses full control over the process and the productivity expectations, it could have a really material effect on the business — or at least that’s their fear,” said Alec MacGillis, author of Fulfillment, a book about Amazon’s logistics.

At Bessemer, Amazon has held “captive audience” meetings, in which consultants talk to small groups of employees about unionisation. According to people in the meetings, warehouse workers were told wages could drop, benefits could be taken away and employees could be forced to pay membership dues.

Amazon prefers the term “educational sessions” for the mandatory meetings, which it says give “employees the opportunity to ask questions”.

The RWDSU has mounted a national legal challenge to captive audience sessions, taking encouragement from recent comments from the NLRB’s general counsel that suggested government officials were looking at a possible clampdown on the practice.

In Bessemer, the arguments appear to be resonating. One worker said they were concerned the company might close the facility or that the union might call a strike. “There are those who are slackers,” she said. “If you come to work and do what’s expected there’s no worries.”

An apparent grassroots campaign has placed anti-union posters around the facility. “RWDSU DECEITFULNESS IS WHY WE DID’NT [sic] GET OUR BONUS,” read a poster recently put out on the shopfloor. Amazon said it had nothing to do with the crudely designed material.

The lifting of pandemic curbs makes the union hopeful its arguments will hit home. “You can talk to somebody personally,” said Dale Wyatt, an Amazon worker and union rep. “They’re intimidated at Amazon. They’re afraid that they’re watching them, listening to them.”

But such is the staff turnover at the company, the union has estimated about half of the bargaining unit were not employed by the company at the time of the first vote.

“When you’re at that level of turnover it’s so hard to build solidarity because you barely know each other,” said MacGillis. “You’re spending more time with a robot than you are with your co-workers.”

Christy Hoffman, the UNI Global Union general secretary, who had flown from Geneva to lend support, said: “If Amazon emerges as a huge modern company shunning its workforce from having any meaningful say, it’s terrible for the future of work.”