India’s biggest start-ups are turning thrifty amid a new reality in which capital has become hard to come by.

At online education start-up Vedantu, one of 44 companies to surpass a $1bn valuation amid a funding frenzy last year, chief executive Vamsi Krishna told employees in an email on May 18 that “capital will be scarce in the coming quarters”. Vedantu will lay off 424 executives, slash spending on acquiring new users and scrap “non-core” initiatives to preserve enough capital for 30 months. The lay-offs came weeks after another 200 jobs had been axed.

Cars24, which gained a $3.3bn valuation trading used cars, has cut 600 jobs. Meanwhile Meesho, an ecommerce start-up valued at $4.9bn, has asked 150 employees to leave.

At online education start-up Unacademy, which soared to a $3.4bn valuation, 1,000 people have lost their jobs, while 200 have gone from Fulenco, a furniture rental start-up. Video commerce start-up Trell — which is under scrutiny for alleged financial irregularities — has sacked roughly 300 employees and healthcare start-up MFine about 500.

“The coming days will be more painful for growth-stage companies,” said one investor at a growth capital provider. “A lot of these companies look fragile despite raising a lot of money at very high valuations, and therein lies the problem — they still look fragile.”

Food delivery start-up Swiggy, which earlier this year was valued at $10.7bn, shut down its subscription service for daily essentials in early May in five of the six cities where it operated, despite scaling the business to 200,000 daily orders from about 6,000 in mid-2018. In an email to employees explaining the unit’s closure, Swiggy hinted big volumes alone were no longer enough.

“While we are now an inalienable part of our consumer’s life, we unfortunately are yet to demonstrate a clear path to profitability,” the group said. “Today, we find ourselves in a situation where we end up spending a significant amount of time and money in managing the business — distracting ourselves from our primary goal of establishing the business market fit.”

Ride-hailing company Ola is also scaling down its food and grocery delivery services.

Together these start-ups have raised about $4bn since January 2021, with Swiggy accounting for about half of that. All of them are in the red.

Shailendra Singh, managing director at Sequoia Capital India, wrote on Twitter in mid-May that board meetings were “now focused on efficient growth, sustainable unit economics and pragmatic capital allocation”. “Frugality is back in fashion,” he added.

From trimming workforces to shutting down unprofitable business units, the start-ups are pulling out all the stops to save for a rainy day as investors turn cautious amid the global meltdown in public markets. This marks a big change from last year’s aggressive expansion, when start-ups spent heavily on marketing and hired employees on high salaries as they rode a funding boom.

India’s top 50 advertisers in 2021 included 15 start-ups operating in markets that included online education, financial services, fantasy sports and cryptocurrencies. Some managed to outspend household names like Reliance Industries, Procter & Gamble, Google, Mondelez, ITC, Coca-Cola, PepsiCo, Nestlé and L’Oréal.

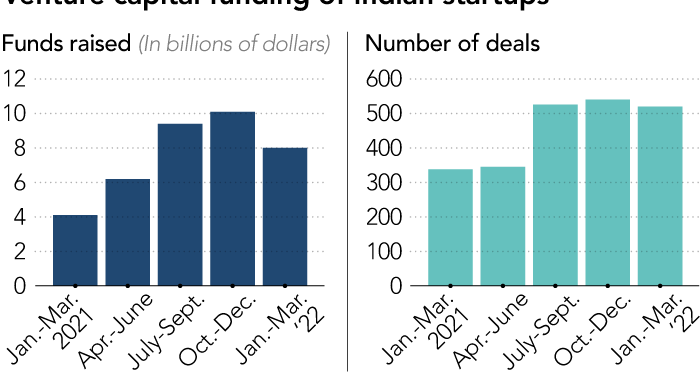

Indian start-ups raised $8bn across 520 deals in the January-March quarter, down 20 per cent from the $10bn pumped in the October-December quarter, according to data provider CB Insights.

“Last year, people were fighting to say yes, but this time there are more people finding a reason to say no,” said Shivakumar Ramaswami, founder and director of investment bank Indigoedge. “Most people are scared to price [a deal] in this market because they don’t know where the bottom is.”

As a result, the bar for investment is much higher this year. “Investors who were valuing start-ups at revenue multiples last year now want to value them at net earnings multiples,” said one investment banker. “It’s a function of the broader markets.”

Technology stocks in the US such as Peloton, Netflix, Palantir, Rivian, Snowflake, Robinhood and Opendoor have borne the brunt of aggressive selling off, with Nasdaq tumbling 28 per cent since the start of the year.

Closer to home, India’s benchmark stock index has slipped 11 per cent in the same period. Tech stocks such as Zomato, Paytm and Policybazaar that listed on bourses last year are all trading below their issue price. Small investors shunned the shares of logistics start-up Delhivery that launched its initial public offering this month.

The slowdown is unlikely to ease soon despite a number of venture companies — including Accel, Elevation Capital and Blume Ventures — raising new funds in the past year. Sequoia Capital has received a commitment from investors for a gargantuan $2.8bn to be invested across India and south-east Asia, but has delayed closing the fund in the wake of alleged financial irregularity in a portfolio company.

“Understand the poor public market of tech companies significantly impacts VC investing,” said Silicon Valley incubator Y Combinator in a note to its portfolio companies. It added that funds would find it harder to raise money and that, if they did succeed, investors would expect more “investment discipline”.

“As a result, during economic downturns, even top tier VC funds with a lot of money slow down their deployment of capital (lesser funds often stop investing or die),” Y Combinator said.

Prayank Swaroop, partner at Accel, says companies have to perform “exceptionally well” to raise capital. “The era of free money is at a pause, till this uncertainty passes over.”

A version of this article was first published by Nikkei Asia on May 24. ©2022 Nikkei Inc. All rights reserved.