Technology transforms jobs, rarely does it eliminate them. But there are exceptions: lamplighters, elevator attendants and telegraph operators have all but disappeared. Astronauts might soon be added to that list, according to two space experts. Robots are capable of exploring the universe more speedily, cheaply and safely than “spam in a can” (as early astronauts called themselves). Our creations can boldly go where humans themselves fear to tread.

For astronauts to be written out of the space exploration script would be painful. For as long as humans have gazed at the heavens, they have dreamt of floating among the stars. Opinions vary on the subject, but I for one am a space romantic. Nothing could be more thrilling than to see our planet from outer space, as memorably captured in the Blue Marble photograph taken by the Apollo 17 crew.

However, in The End of Astronauts, Donald Goldsmith and Martin Rees make a convincing case that blasting humans into space has become a wasteful indulgence. Far more can be accomplished by robotic missions of scientific discovery, of which they approve. “We do not need astronauts as space explorers,” they bluntly state. That conclusion is all the more telling given the authors’ expertise: Goldsmith is a veteran writer on space, while Lord Rees is Britain’s Astronomer Royal.

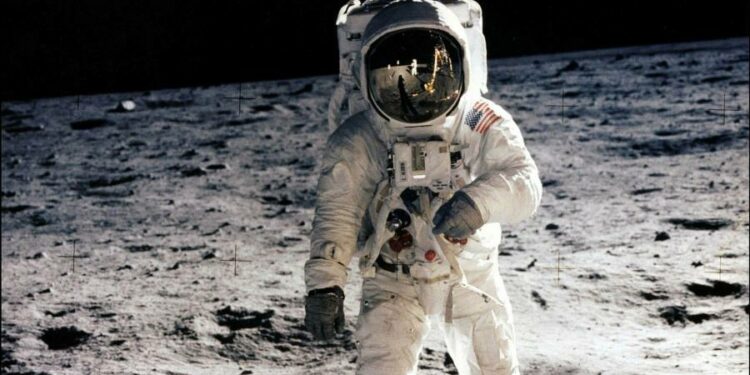

It is hard to disagree with their cold logic. Ever since Yuri Gagarin first went into space in 1961, Russian cosmonauts and American astronauts have been seen as humanity’s heroes, embodying our collective endeavour, ingenuity and courage. Since then, almost 600 astronauts from 41 countries have orbited the Earth, spending a collective 57,000 days in space.

But the costs are astronomical and beyond boosting the world’s feelgood factor, astronauts do not do much that robots could not now do better. For the past two decades, the International Space Station has sustained a crew of three to six orbiting astronauts, clocking up 20,000 astronaut days. Given the total cost of the ISS is about $150bn so far, that equates to some $7.5mn per astronaut-day, or $675mn for a three-month stay, the authors calculate.

Some argue that humans remain irreplaceable for tricky activities, such as space repairs. But even here robots are becoming increasingly capable of performing these tasks at a fraction of the cost. Visiting astronauts have repaired the Hubble Space Telescope five times during the 32 years since launch — and the cost of these repair missions would have paid for the construction and launch of seven replacement telescopes.

The commercial spin-offs of human space flight have been hotly debated. The economist Deirdre McCloskey called them the “Tang Fallacy”, after the false belief that the orange powder drink Tang was a byproduct of the space programme. Moonshots may lead to some technological breakthroughs — such as space blankets and freeze-dried food. But equivalent spending on other priorities, such as climate change, might generate even more.

Some argue that turning Homo sapiens into a multi-planetary species is a sensible insurance against a mass extinction event on planet Earth. But there is an even stronger argument for ensuring we preserve our miraculous home rather than trying to terraform a planet B. Besides, as the political scientist Daniel Deudney has argued, the likelihood is that space colonies would be nasty places, tending towards “unfreedom” given the need to manage scarce resources and mandate safety.

Whatever the logic, nothing is going to stop billionaire adventurers, such as Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos, from pursuing human space flight through their privately funded companies, SpaceX and Blue Origin. Nor should it. That pioneering spirit must endure even though Musk’s ambition to walk on Mars is an immense challenge. In 1969 it took the Apollo 11 mission just over three days to reach the Moon. Modern rockets take seven months to travel to Mars.

Fifteen unmanned spacecraft have already made the trip and seven have landed on the surface, releasing rovers to send back precious data. Publicly funded space agencies should focus on these and other even more remote robotic missions.

The trouble is that without the romance of human space travel, such agencies may struggle to win funding. “No Buck Rogers, no bucks”, as the Washington saying goes. Whatever their merits, robots still lack emotional appeal. Perhaps the answer is for space agencies to subsidise augmented reality headsets and allow us all to hitch a virtual ride.

The writer is founder of Sifted, an FT-backed media site for European start-ups