DJ Justin Blau was opening up for his superstar peer Avicii on a beach in Mexico when he met the Winklevoss twins, who introduced him to bitcoin. “It couldn’t get more cliché than that,” he says of his 2014 meeting with the Harvard classmates of Mark Zuckerberg, who have since become blockchain evangelists.

As a university student, Blau dropped his finance studies and turned down an internship at asset manager BlackRock to pursue a DJ career. Years later, he has combined his dual interests — music and finance — into a business aimed at disrupting the record industry through blockchain technology. On Tuesday he teamed up with longtime friend Diplo, the popular electronic musician, to sell 20 per cent of the streaming royalties of a song to fans in the form of digital tokens.

“I’m just fascinated with the idea of there being value for the ownership of music,” Thomas Pentz, known professionally as Diplo, told the Financial Times. “The more people behind your record, whether its fans or investors who are interested in the technology, it’s great to have more people on a team.”

In recent months the hype surrounding Web3 — the buzzword for a decentralised, blockchain-powered iteration of the internet — has swept the music industry, drawing the world’s largest music companies to the fray and fuelling hope that non-fungible tokens will become a new source of money for musicians.

To sell an NFT, musicians assign their song, video or other piece of media to a digital token. The token is sold through an online auction enabled by blockchain technology, which keeps a record of the transaction. Beyond songs or images, NFTs could also be used to sell perks such as backstage passes or meetings with stars.

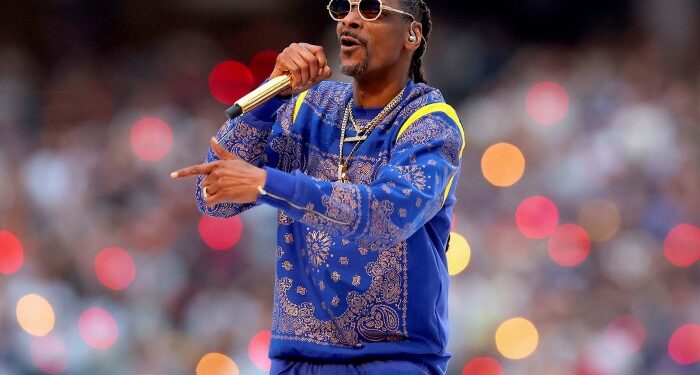

Head-spinning examples abound. Rapper Snoop Dogg in February sold an NFT attached to Bacc on Death Row, his latest album, that reportedly generated more than $40mn in sales in just five days. DJ Steve Aoki claims he has made more money through NFTs than he did from a decade’s worth of advances from record labels.

“Some of these valuations are out of control. As an investor, I’m seeing a lot of it and have to laugh occasionally,” said a senior executive at a major music label.

But after getting knocked over by the internet via the advent of file-sharing company Napster two decades ago, the big music companies are looking to get ahead of technological change this time around, making them willing participants in the market.

Universal Music, the group behind Taylor Swift and Drake, has struck partnerships to create NFTs for its artists — including a virtual band featuring characters from the Bored Ape Yacht Club — as have rivals Sony and Warner.

After spending more than half a billion dollars buying the copyrights to Bob Dylan’s songbook, Universal and Sony are now working with the musician to sell Bob Dylan NFTs. Spotify has been drawing up plans to add blockchain technology and non-fungible tokens to its streaming service, the FT reported earlier this month.

“There’s been a lot of waxing and waning of irrational exuberance around this space”, said Jonathan Dworkin, senior vice-president of digital strategy at Universal. “As the smoke now starts to clear, there’s some really interesting opportunities . . . there’s a real revenue opportunity” he said, pointing to the ways tokens can directly connect fans with artists.

But so far, most participants in music NFTs are crypto enthusiasts rather than ordinary fans, and the market is tiny — taking in just $83mn in primary sales last year, according to industry blog Water & Music.

There are plenty of sceptics. “It feels like the music industry is desperately trying to find a way to insert itself into NFTs without actually thinking: what is the underlying use case?” said Mark Mulligan, analyst at Midia Research.

Mulligan argued it is hypocritical of musicians to sell streaming royalties to fans, after years of complaints over the minuscule payments artists themselves receive in streaming royalties. “If you sell someone a fraction of that fraction, and charge them a lot of money for it because it’s an NFT, I’m not sure how it would be a valid investment.”

Diplo maintained it is a good investment for music lovers. “For a fan, what you can do is buy merch, you can buy tickets for a concert . . . but really, this is what you’re a fan for. You’re a fan because of the music.”

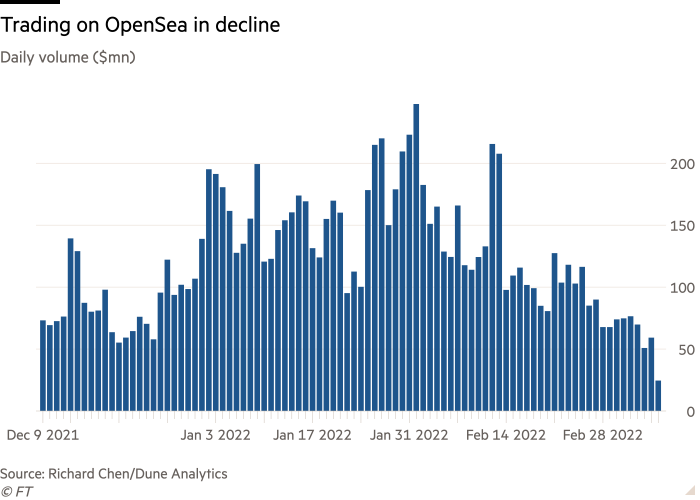

Most of the $17.7bn worth of NFTs traded last year were for visual art, games and collectibles, according to market tracker Nonfungible.com. While the NFT market itself has shown signs of slowing with daily trading volumes on OpenSea, the biggest marketplace for NFTs, falling since the start of the year, some people view music as a space ripe to break out this year.

Royal, Blau’s company, is among the most prominent of a crop of music blockchain start-ups that aim to revolutionise the industry. Through Blau’s personal connections — and Silicon Valley optimism around blockchain — Royal secured $55mn from investors including Andreessen Horowitz and Peter Thiel, without ever making a pitchbook.

Blau, who last February sold $12mn in NFTs attached to his songs, wants to scale that into a business through which ordinary fans can own music, “as opposed to just record labels, private equity and hedge funds”.

Royal’s project with Diplo, for example, offers fans the option of paying $99 for a token representing 0.004 per cent of the streaming royalty rights to “Don’t Forget My Love”, the first single from his recently released album. For $999, you receive 0.05 per cent of the royalty rights, as well as an “exclusive DJ mix,” while $9,999 gives you 0.7 per cent of the royalties and a meeting with Diplo at a concert. These tokens do not equate to owning the copyrights to songs.

Asked whether this is a good investment for fans, Blau said that there is an emotional attachment to the ownership, as well as the possibility of betting on the success of an artist before they become a star. “In real estate . . . if you own a single family home there’s the rental income and then there’s the actual asset appreciation, right?” he argued.

Another longtime music label executive said that some of these projects “haven’t hit because people are concerned about the exploitative nature”, referring to the questionable investment value of streaming royalties.

“There’s a lot of detractors that say: there’s only rich white dudes that are doing this and driving up the price of NFTs.

“But I don’t think we can discount that technology is evolving,” the executive added. “We’ve been in playlist land for the past decade. I think that blockchain tokens are going to be fundamental to our world in 10 years, and anyone that says that’s not true is not looking back on history.”