The writer is a former FT Moscow bureau chief

After President Vladimir Putin launched his military assault on Ukraine last month, Kyiv urged the international community to punish Russia by switching off its internet connections. Icann, the apolitical, non-profit organisation that runs the internet’s “address book”, rightly refused the demand, arguing that such a move “would have devastating and permanent effects on the trust and utility of this global system”.

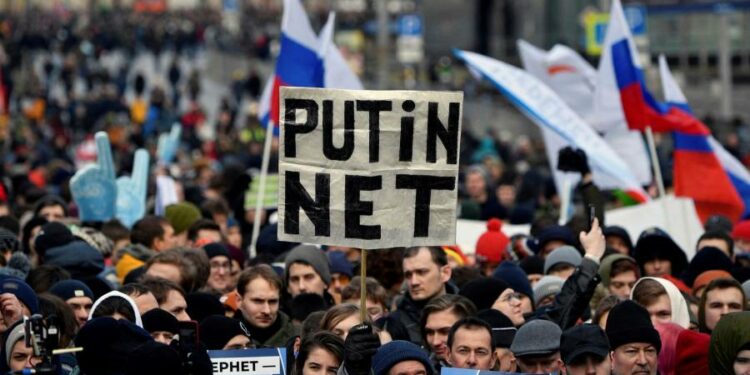

But Russia is increasingly intent on cutting itself off from the rest of the digital world by accelerating the creation of a “sovereign internet”. Like other authoritarian governments, Russia is determined to tighten controls over the internet so as to track users, censor information flows and prevent the mobilisation of political opposition.

This is a further politicisation and fragmentation of the global communications network: the internet is fracturing into the “splinternet”. According to Access Now, an international human rights group, there were at least 155 internet shutdowns across 29 countries in 2020, compared with 75 in 2016, as national governments sought to silence protests, swing elections or conceal human rights abuses. “The internet is this enormous resource for all humanity. Technically it is very robust but politically it is quite fragile,” says Andrew Sullivan, president of the Internet Society. “People are trying to shut it off. That is a tragedy.”

For many years, Russia’s government saw the internet as a force for modernisation and economic development. Unlike China and Iran, which developed their own carefully managed networks, Russia enthusiastically wired itself into the rest of the world with the encouragement of Russian and western technology businesses. Strong local internet companies, such as VKontakte and Yandex, emerged and an innovative app economy flourished. By 2020, almost 85 per cent of Russians used the internet.

However, the security hawks around Putin, known as the siloviki, grew alarmed about the loss of political control after mass protests in 2011 against electoral fraud. They have since been progressively disentangling Russia from the global internet and increasing controls. VKontakte, dubbed Russia’s Facebook, was taken over by Kremlin allies. The government tightened the screws on YouTube, Twitter and Facebook in an attempt to censor prohibited content. In 2019 Putin approved a sovereign internet law instructing all service providers to channel traffic through filters controlled by the Kremlin’s digital censor Roscomnadzor.

The war in Ukraine is further hiving off the Russian internet as the Kremlin blocks more foreign services, such as Facebook. The crisis has also sideswiped Yandex, known as Russia’s Google, and many other local tech companies. Russian tech workers flee the country, fearing further clampdowns. Russians may still be able to access the global internet via virtual private networks (VPNs) and the dark web but it may become harder.

The irony is that Russia’s increasing isolation will severely dent the Kremlin’s ability to achieve a second important objective: establishing greater technological sovereignty in 5G networks, artificial intelligence, operating systems and cloud computing. Western sanctions will cut off Russian imports of critical tech products and services. Several foreign companies, such as Microsoft, Apple, Samsung, Oracle and Cisco, are refusing to sell to Russia or shutting down operations there. “Russia’s tech potential is going to be destroyed for a long time. This industry requires many, many years of investment and a favourable environment. Russian products and services are toxic now,” says Alena Epifanova, research fellow at the German Council on Foreign Relations and author of a report on Russia’s quest for digital sovereignty.

In spite of early dreams of the internet as an open and universal resource, it is fast splitting into three dominant “infospheres” with different approaches, interests and rules: a libertarian US model; a more regulated European one; and a state-controlled Chinese version. For those of a dystopian disposition, it has unnerving echoes of the three superstates in George Orwell’s novel Nineteen Eighty-Four: Oceania, Eurasia and Eastasia.

Russia is clearly trying to establish a fourth Russophone infosphere but it is in a weak position given the lack of strong domestic technology manufacturing. Moscow now has no choice but to fall back on Chinese equipment and expertise. That may also worry the siloviki. And Beijing is itself being squeezed by tightening US restrictions on tech exports. As elsewhere, Putin may achieve short-term tactical advantage by lowering a digital iron curtain, but Russia is facing long-term strategic loss.