UK ports are on course for their worst year since 1983 after declining North Sea oil production and Brexit put a large dent in cargo volumes.

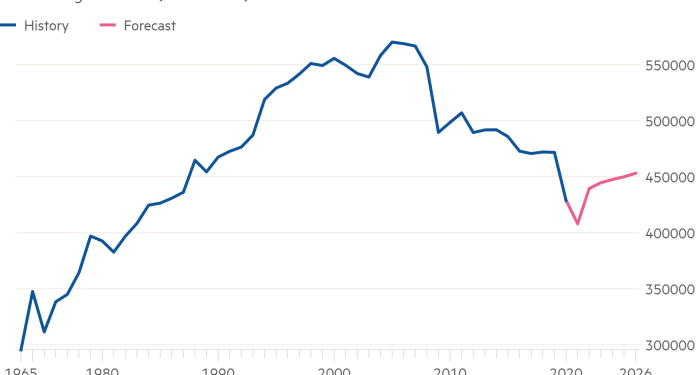

Goods handled at the nation’s ports are expected to hit a nadir of about 408m tonnes this year, down 13.5 per cent on 2019, according to research by Drewry Maritime Advisors commissioned by the UK Major Ports Group.

Demand for consumer goods and some other categories such as building materials have bounced back quickly after the first lockdown in 2020, which together with the global disruption to supply chains has caused some congestion at UK ports.

However, the UK ports have suffered from a significant decline in oil production, which plays an important role in UK trade and accounts for around a third of port volumes.

Oil production at certain North Sea sites was disrupted due to a drop in demand for energy as people travelled less because of the coronavirus pandemic.

The end of the Brexit transition period at the start of this year also contributed to the decline as the volume of accompanied roll-on, roll-off cargo — which includes a range of consumer and trade goods — sharply dropped because of new border controls and the driver shortage.

Tim Morris, chief executive of the UK Major Ports Group, a trade body for the largest operators, said that it had been a “challenging year” and that the “shocks of the pandemic have compounded long term structural change such as the shift from oil and the impact of decarbonisation on the UK economy.”

Although volumes will begin to recover this year they are not expected to reach pre-pandemic levels until 2026 because of the continuing slide in demand for oil and gas products as the UK advances decarbonisation plans.

The release of data showing the decline in oil handled by UK ports follows Royal Dutch Shell’s withdrawal last week from the controversial Cambo project in the North Sea amid fierce debate over the need to bolster energy security by investing in domestic fossil fuel production.

UK oil demand has been in decline since around 2005 because of the shift in the energy system to renewable power. That has led to a long-term decline in liquid bulk volumes passing through ports in Scotland that receive North Sea supplies and others near refineries such as Southampton and Immingham.

The decline in volumes comes as ports in the UK, mostly owned by the private sector, need to invest in infrastructure such as electric chargers to decarbonise shipping. Operators say government support is needed to make those investments a reality.

The bright spots in the years ahead are for ports serving containerised freight, helped by the surge in demand for consumer goods from Asia and so-called break bulk goods such as steel and other materials used in construction, the report said.

Morris said that ports have been investing and developing their businesses in higher growth categories like containers and unaccompanied trailers, as well as alternative revenue streams that depend less on high volumes such as logistics, warehousing and green energy, including manufacturing for wind farms, for example.