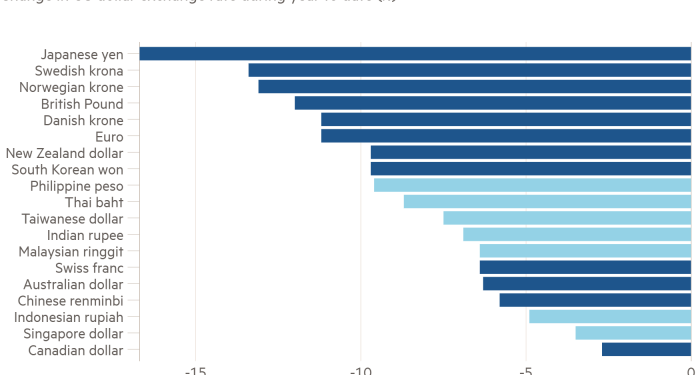

South and south-east Asian currencies are outperforming their developed-nation peers as economic reopening and swift central bank action have helped offset the impact of a stronger US dollar.

Indonesia’s rupiah and Singapore’s dollar — the top performers in the region — have fallen less than half as much as the euro, which is down 11 per cent this year against the US currency.

While the Bank of Japan’s ultra-loose monetary policy has pushed the yen down 17 per cent against the dollar, tightening by India’s central bank has limited the rupee’s drop to less than 7 per cent.

Those moves have come as the Federal Reserve has taken aggressive action in recent months to raise interest rates in a bid to tackle red-hot inflation. That vigorous policy stance has propelled the dollar higher and weighed heavily on the currencies of developed and emerging markets.

But several south and south-east Asian countries got in ahead of the Fed, meaning that their currencies have fallen only about 7 per cent on average in the year to date, according to Financial Times calculations based on Bloomberg data, compared with an average drop of more than 11 per cent for a range of European currencies.

“In 2013, a lot of the currencies that got hit by the taper tantrum, their fundamentals were poorer,” said Mansoor Mohi-uddin, chief economist at Bank of Singapore, referring to the market tumult that followed then-Fed chair Ben Bernanke indicating a planned withdrawal of the central bank’s bond-buying programme.

He added that many central banks had been quicker to tighten policy or even pre-empt the Fed, while the current account deficits that left the region so vulnerable in the past were far less of a concern.

“That gives a shield to these countries in terms of their exchange rates,” Mohi-uddin said, adding that long-delayed economic reopenings throughout the region were also adding strength.

The region’s outperformance comes despite substantial differences in monetary policy and the impact of surging commodity prices.

Singapore’s dollar has dropped just 3.5 per cent this year as the Monetary Authority of Singapore has rapidly tightened policy in response to the Fed’s sharp moves.

Irene Cheung, senior Asia strategist at ANZ, said Singapore’s currency had done well “first because of the very aggressive policy stance of the MAS and second the revival we’re seeing in tourism and the telecoms sector”.

She added that while Singapore was vulnerable to more substantial rises in energy prices already hitting European economies, export-focused countries in the region including Indonesia and Malaysia were actually benefiting from higher commodity prices.

“The [Indonesian] rupiah has weakened but it’s not even as bad as the start of the pandemic,” said Cheung. She added that while Indonesia’s central bank had yet to raise rates this year, it was still running a “very good trade surplus” thanks to exports of commodities including natural gas and palm oil.

Resilience for the Indonesian and Malaysian currencies is backed up by investment flows this year. High-frequency data from JPMorgan on non-resident portfolio flows into local markets show net purchases of $5.4bn and $1.3bn, respectively, of Indonesian and Malaysian securities. In contrast, foreign investors have dumped about $29bn of Indian stocks and bonds.

Yet even India’s rupee, which this week neared a record low of Rs80 to the dollar, is only down about 7 per cent compared with the free-falling yen.

A widening current account deficit has put pressure on the rupee, India’s finance ministry said in its latest monthly report, with the country’s foreign exchange reserves declining by $34bn from January to June amid high global energy costs and surging demand for gold.

“As long as we’re depreciating in line with other emerging markets currencies the [Reserve Bank of India] should be OK with it,” said Jayesh Mehta, country treasurer for India at Bank of America.

He added that India’s current account deficit was still within a manageable range and the central bank was unlikely to resort to large-scale intervention as it did in 2013.

“I don’t think they’ll need to do that,” Mehta said, “but that is a backstop — you have the ultimate firepower there.”