Paul Myners, the opposite of a conventional City grandee, took great delight in boardroom battles. While he made a fortune in fund management he never hesitated to attack what he regarded as the shortcomings of the industry.

When invited by Gordon Brown, then chancellor of the exchequer, to become a minister and help tackle the financial crisis, he clashed with the chiefs of ailing banks, especially RBS chief executive Fred Goodwin. After one round of fraught rescue discussions at the Treasury, Goodwin remarked: “this isn’t a negotiation — it’s a drive-by shooting”.

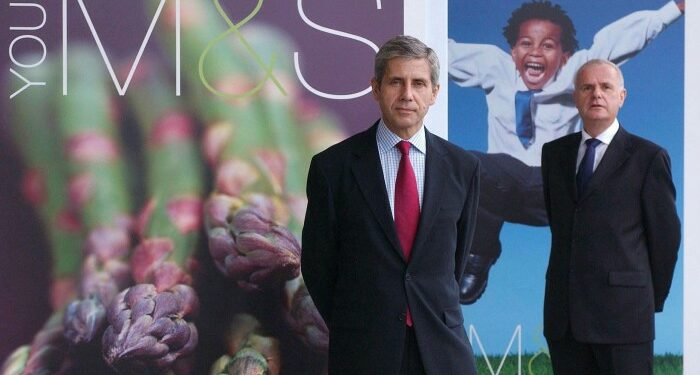

As chairman of Marks and Spencer, Myners clashed noisily with Philip Green after the controversial retailer made a hostile approach — and successfully saw him off. “He was never one to shirk a fight,” recalls Lord Stuart Rose, then the retailer’s chief executive. “No tactic was off the table.”

Baron Myners of Truro, who has died aged 73, was adopted at the age of three from an orphanage in Bath by Thomas and Caroline Myners, a butcher and hairdresser in the Cornish city. He attended Truro School on a scholarship before obtaining a degree in education at London University. This was followed by two years as a teacher in south London: he concluded that education was not his métier, and left to work briefly as a “blue button”, or dealer’s assistant, on the floor of the London Stock Exchange.

Myners moved to the Daily Telegraph in the early 1970s to write for its Questor investment column and drew the attention of the merchant bank N M Rothschild, which recruited him to its fund management business in 1974. He became a director, working in London, Kuala Lumpur and Hong Kong.

In 1985 he made a career-enhancing move to Gartmore Group, which was owned by British & Commonwealth — a bold step given that Gartmore’s performance had been damaged by losses in its US venture capital business. Yet Myners, as chief executive and then chairman, turned Gartmore into a powerful force in pension fund, unit trust and investment trust management.

During his tenure, British & Commonwealth sold Gartmore to Banque Indosuez, which eventually sold the business in 1996 to NatWest in a £472m deal. At that point Gartmore had nearly £25bn funds under management compared with £1.2bn when Myners had joined. As part of the deal, Myners was given a seat on the NatWest board from which he was ejected by Goodwin when it was taken over by RBS.

At Gartmore, Myners increasingly became absorbed with corporate governance issues. Unlike most fund managers at that time, he spoke out on executive pay, particularly excessive rewards for poor performance. He argued that institutional investors should be more active in confronting underperforming companies.

Gordon Brown and his Treasury officials took note. The New Labour chancellor worried that risk-averse institutional investors were restricting growth by neglecting start-ups in favour of listed companies. In his 2000 Budget, he announced what came to be known as the Myners review, its scope enlarged by the financier to cover the whole institutional investment process. In characteristic poacher-turned-gamekeeper-style, Myners attacked fund managers for prioritising their own business risks at the expense of clients’ interests, arguing this led to a misallocation of capital. He observed that the average pension fund trustee spent only 12 hours a year on asset management in an industry overseeing £900bn. These assets, he said pointedly, should not be managed as a churchwarden or scout group would conduct their financial affairs.

Myners proposed a voluntary set of principles for investment decision-making, and railed against what he called ownerless corporations. This applied especially to RBS, where he said institutional shareholders had encouraged the bank’s excessive risk taking.

While the Myners report had a marked impact, many of its criticisms of benchmarking practices, opaque transaction costs and conflicts of interest remain live issues. Yet his troubleshooting roles in British boardrooms were mainly successful. After seeing off Green at M&S, he chaired a number of other companies including Land Securities and the Guardian Media Group. He was made a Labour peer in 2008 in order to join the government, but later switched to being a cross-bencher.

Myners’ one conspicuous failure arose in 2014, when his governance reform recommendations at the Co-op were fiercely opposed by fellow board members, who included a plasterer, a nurse and a gardener. He quit the post in frustration after three months — a rare mis-step in an otherwise stellar career.