Greetings from Denver where I have recently been scouring the local television channels and news stands to see how the media landscape looks in the heartland of America (rather than my usual coastal haunt of New York). I have been struck by how prominently climate change issues have featured, not just in the local paper (the Denver Post), but also in USA Today, which is often the main national publication on sale around here.

Last week, for example, there was a big piece in USA Today about the dangers of climate science denial: a research group called Advance Democracy reported that in the second half of last year an average of 679 social media posts appeared each day with climate change denial terms such as “climate fraud”, “climate change hoax”, or “climate cult”. Strikingly, the onslaught increased, not decreased, after Facebook tweaked its algorithms last year to flag misleading content — and spiked during the COP26 climate summit. Yikes.

That is depressing. But it is also encouraging that this story is being featured in the press, and that tech companies feel the need to act. If you want to see a novel response, check out this fascinating speech at the OECD on “mental immunity”.

In today’s newsletter we talk about two other signs of change: NGOs are having more success in prompting western chocolate companies to think about their supply chains — and ESG topics have suddenly got central billing in the Sundance Film Festival this year. Read on. — Gillian Tett

A new recipe for Nestlé?

Just over a year ago, a campaign group called International Rights Advocates sued seven big western companies involved in the chocolate trade — Nestlé, Hershey, Cargill, Mars, Mondelez, Barry Callebaut, and Olam — over their use of child labour in their supply chains.

The case initially seemed unlikely to have much impact, given that NGOs have complained for years about these issues. However, in contrast to the tactics used a decade or two ago, the activists have not just embraced legal routes to press their case — and publicity about innocent children — but they have been hyperactively lobbying the big investors in these chocolate groups, particularly entities that have made previous ESG commitments such as the Government Pensions Fund of Norway and BlackRock.

It is unclear whether this prompted BlackRock or the Norwegian investors to lobby the companies themselves. But an announcement last week from Nestlé was striking: after years arguing that the child slavery issue was a problem that lay beyond its control, it has announced plans to triple its cocoa sustainability funding to SFr1.3bn ($1.4bn) over eight years — and, most crucially, to start making direct payouts to African cocoa farmers in a bid to remove child labour from its supply chain.

The idea is that households involved in cocoa cultivation and harvesting will “receive payments for sending their children to school, implementing good agricultural practices like pruning, and sustainable measures such as planting shade trees”, as the FT wrote. Those diversifying their incomes through other means, including additional crops and livestock, will also be paid. The Nestlé managers hope this incentive-based approach will raise standards more effectively than simply saying they want to abolish the problem.

Will it work? In all honesty it is unclear, given that a widely cited study by the University of Chicago estimates that 1.56m children, or 45 per cent of agricultural households in the Ivory Coast and Ghana — the two biggest cocoa-producing countries — have been engaged in child labour in recent years. But the initiative has had a cautious welcome from some NGOs. Antonie Fountain, managing director of the Voice Network, an umbrella group for 17 non-profit organisations, told the FT the tactic “could be successful” and “maybe every company will need to do this in the future”.

So we will be watching to see whether the other six cocoa groups follow suit, particularly since entities such as Mars have been stepping up their own ESG initiatives. (The privately held group recently took the novel step of giving ESG responsibilities to the head of procurement.)

There are at least three key points that the wider — non-chocolate — business world should note. The first is that NGOs are getting savvier in terms of how they are tracking and targeting asset owners in relation to ESG issues in their supply chains. Second, activists are doing this not just in relation to “E” factors, but “S” topics too; the type of lateral vision associated with “scope 3” accounting systems for carbon emissions is being transposed on to social issues.

Third, insofar as companies are being forced to take a lateral — not tunnel — view of their operations, this is prompting some to get more imaginative with their supply chains. The onus is now on companies to take direct action to fix embarrassing issues — rather than simply hoping that NGOs or governments can fix them. One sign of this shifting mentality can be seen in Walmart’s recent announcement that it will provide direct finance to its suppliers to help them decarbonise, since it cannot assume that multilateral banks or private banks will provide the funds.

Nestlé’s move is in a similar vein, since it now recognises that it cannot rely on governments or NGOs alone to stop child labour. Moral Money suspects that this trend will keep spreading. Milton Friedman might spin in his grave. (Gillian Tett)

The power of film to change minds on climate change

On Christmas Eve, Netflix released Don’t Look Up, a film about a comet heading directly to Earth and humanity’s incompetent effort to survive it. Thanks in part to its all-star cast, the movie quickly became a phenomenon and was Netflix’s second-most popular film ever (as of January 20).

The film’s director, Adam McKay (he did The Big Short) has said the comet symbolises climate change. The story holds up an uncomfortable mirror before all of us as it satirises the response to global warming.

The popularity of the film suggests that movies — and entertainment broadly — have found a way to incorporate the climate crisis. But can films change minds on global warming?

The Sundance Film Festival, which concluded on Sunday, included a handful of films that embraced the climate change conundrum.

First, All That Breathes, a film about a fight to protect birds in the polluted New Delhi air, won the world documentary grand jury prize. It follows the story of brothers Mohammad Saud and Nadeem Shehzad who started a rescue centre for black kites, scavenger raptors. The birds are crippled by the city’s punishing air pollution.

The climate change concern is tucked into the background of the film, which is primarily a human interest story about the brothers and their passion for the black kites. But a second climate change documentary at Sundance tackles at the climate crisis head-on. To The End features four women fighting global warming, including congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez.

Sundance, like many film festivals, is as much a celebration of movies as it is a dealmakers’ bazaar. Netflix, Amazon and the other streaming services hunt for films at Sundance and will shell out $10m or more for movies.

With the climate change crisis making its way into film, more young people will be exposed to the issue in a way that older generations were not, highlighting for them the importance of fighting global warming. (Patrick Temple-West)

Chart of the day

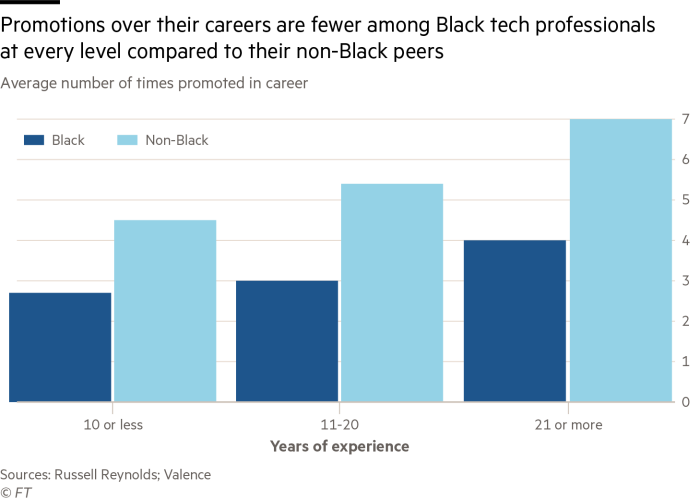

Black tech talent are promoted through the ranks at a dramatically slower pace than other workers, headhunting company Russell Reynolds found in a survey released today.

Black employees were found to receive three promotions on average over 10-20 years, while their non-black peers received over five promotions on average in the same period. Black employees were also especially likely to suffer from a lack of transparency and consistency in performance reviews, the study found.

Smart read

-

Many leading economists see carbon taxes as a crucial part of the answer to fighting climate change. To make them palatable to voters, some argue, the proceeds should be paid out in full to households. But in the few places where this has been tried, has it won popular support? A recent study of the free money schemes in Canada and Switzerland is not wildly encouraging, Robinson Meyer at The Atlantic wrote.