Inside a cramped photocopying kiosk in Mumbai, Umesh Khamkar was checking his phone every 30 minutes. He is the tiny shop’s proprietor, but Khamkar was focusing on his other more lucrative business as a day trader.

These days he earns more money trading stocks on an app than with his photocopying machine. Khamkar, a slight man in his fifties, began investing in Indian stocks after the country’s punishing lockdowns in 2020 sent him down a rabbit hole of YouTube investment seminars.

Hooked, he encouraged his friends to start trading. His list of converts now includes the cashier of a nearby restaurant selling pit-stop lunches to commuters.

Khamkar is one of millions of Indians who have started investing in the stock market since the pandemic began.

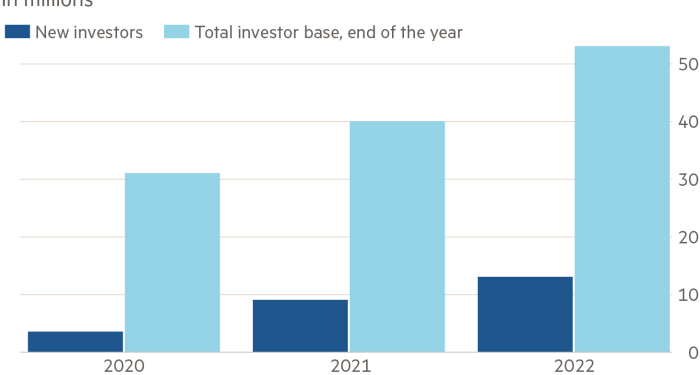

More than 50m investors are registered with the National Stock Exchange, up from 31m two years ago. The NSE does not disaggregate between businesses and individuals, but retail brokerages have reported booming client numbers.

Enabled by technology and access to some of the world’s cheapest data, retail investors now account for 45 per cent of total trading market share in India, with their rise mirroring the surge of traders in the US and UK that have driven meme stock mania.

“Retail investors have now become a force to reckon with since the pandemic started,” said Rajesh Sehgal, managing partner at Mumbai-based Equanimity Investments.

This boom in ordinary people investing in equities, a riskier asset class, has helped fuel India’s stock market bull run, Sehgal said. “There have been at least two or three down moves in the market in that time, but when foreigners or big institutional investors have started selling, retail has been buying.”

That has helped Indian stock prices soar. The Nifty 50 index of India’s largest companies is up 25 per cent year to date, while Mumbai’s Sensex has gained 23 per cent in the same period.

But when indices slump, Sehgal cautioned that retail traders could weigh down the market: “When there is a serious downturn and these retail investors start selling, who’s going to buy it?”

Nithin Kamath, founder and chief executive of Zerodha, India’s largest broker by number of active users, warned that retail investment was “cyclical, every bull market people think the behaviour has changed, but it doesn’t. Essentially people are just getting sucked into greed.”

Zerodha’s customer base has more than trebled in the past 18 to 20 months, from 2m customers to almost 8m today. Kamath estimates that with 10m to 15m orders a day, Zerodha accounts for 10 to 15 per cent of India’s trading volumes.

But Kamath said the significant change was that three-quarters of the new customers are under the age of 30. “I [can’t] think historically when there were so many 20 to 30-year-olds who got into capital markets . . . traditionally people would think about investing in the markets only when they were married and they have some savings,” he said.

Technology has democratised what was previously a “closed club” in trading, said Rajamani Venkataraman, managing director of financial services company IIFL.

According to Bombay Stock Exchange data, 19 per cent of trades were made on mobile devices in November, compared with 3 per cent five years ago.

Mobile devices have also given people living in India’s vast hinterlands access to markets. The NSE said in October that more than half of new traders came from outside India’s top 50 most populated cities.

While many new investors are making their own bets on Indian companies, others want professionals to do it for them.

There are now nearly 19m Indians invested in professionally managed mutual funds, according to Pankaj Chaudhary, junior finance minister.

He said that as of the end of October, the money overseen by these managers had risen 68 per cent year on year.

For amateur stockpickers, risks abound. Many try to snare quick profits from cheap but volatile stocks, such as IT group Equippp Social Impact Technologies or telecoms company Tata Teleservices, while others make leveraged bets that allow them to win — or lose — more money.

“Most people can’t handle leverage and when it goes down, it goes horribly wrong,” said Kamath, explaining why Zerodha does not offer it.

Others are proving to be cautious traders. “There’s a much faster education that seems to be happening,” said Ram Srinivasan, a banker turned start-up founder based in Chennai. “What it took me 10 to 15 years to learn, some of these guys are learning in a couple of years.”

Khamkar, the Mumbai shop proprietor, has grown the Rs20,000 ($264) he invested in early 2020 to Rs530,000. That is a small fortune in a country where Credit Suisse estimates the average individual’s wealth at $14,000.

Khamkar said the markets had been down but he was not flustered. “When the markets are down, people get scared and they sell,” he said, sagely. “That’s when you have to buy.”