Investors this week deserted a trade that has generated big returns since the financial crisis, ditching shares of fast-growing technology companies in favour of staid businesses that had largely been overlooked by Wall Street.

The tech-focused Nasdaq Composite shed 4.5 per cent in the first five trading days of 2022, the worst annual debut since fears of a slowdown in China sent shockwaves across global financial markets six years ago.

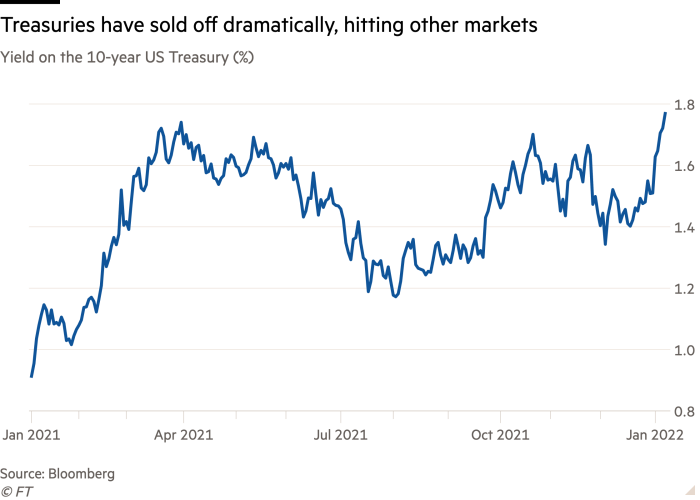

The tech tumble came as US government bond yields surged the most in 28 months, as concerns mounted that the Federal Reserve would need to raise rates more aggressively than was previously expected to tame hot inflation.

“A lot of the air has been let out,” said Jurrien Timmer, head of global macro strategy at Fidelity Investments. “[Speculative tech shares] went to the moon and now that liquidity tide is reversing.”

Tech stocks, particularly those of fast-growing and lossmaking companies whose high prices are predicated on the potential for bumper future earnings, are seen as especially susceptible to rises in rates that diminish those potential future returns. But importantly, this week the sell-off extended to marquee tech names that are among the largest in benchmark US stock indices, including Apple and Google-owner Alphabet.

The US 10-year Treasury yield — a crucial benchmark for global assets — jumped from just 1.51 per cent at the end of 2021 to a high of 1.8 per cent, eclipsing a post-pandemic peak hit in March.

“A lot of fixed-income players went on holiday in mid-December with Omicron still being more of an unknown quantity,” said Ludovic Colin, a portfolio manager at Vontobel Asset Management. “They’ve come back in January realising maybe it’s not that bad . . . That’s why we’ve seen yields getting trashed.”

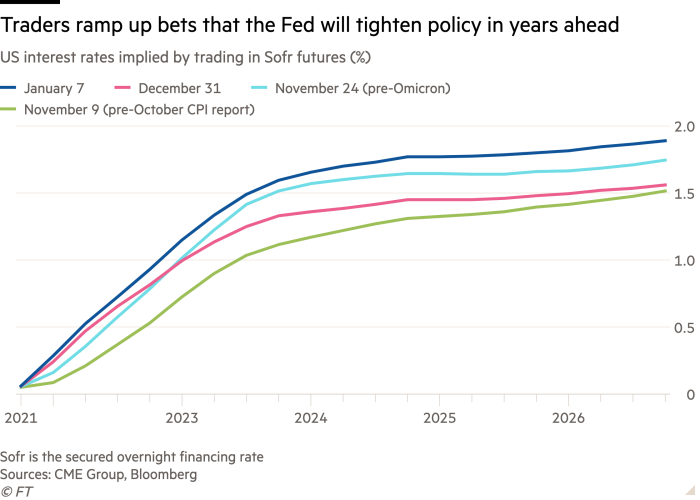

As fear of the severity of Omicron has receded in markets, Fed policy has moved to the fore. Before 2021 was up, the world’s most important central bank had already signalled it would begin to remove crisis-era policy support — put in place in the depths of the coronavirus downturn — more quickly, ushering in a new interest rate rising cycle this year.

This week investors got a closer look at the discussions that took place inside the Fed in December. Minutes of the Federal Open Market Committee’s last meeting showed that policymakers could find cause to accelerate the pace of rate rises. It may even begin reducing the size of its balance sheet this year, which has doubled in size to nearly $9tn since early 2020 thanks to the central bank’s massive bond-buying programme that helped prop up financial markets.

“The fact they are talking about the balance sheet is very significant,” said Mohammed Kazmi, a portfolio manager at Union Bancaire Privée.

Conviction over rising rates solidified on Friday as the US unemployment rate dropped below 4 per cent for the first time since the pandemic was first reported as being on American shores in 2020, with signs of wage inflation building in the labour market.

As yields have risen, so have the fortunes of previously unloved value stocks, as investors have turned away from high-growth companies that were in vogue at the height of the pandemic. Shares of banks, oil majors, big industrial groups and particularly those companies whose fates are closely interwoven with the reopening of the US economy, including airlines and mall operators, have all advanced.

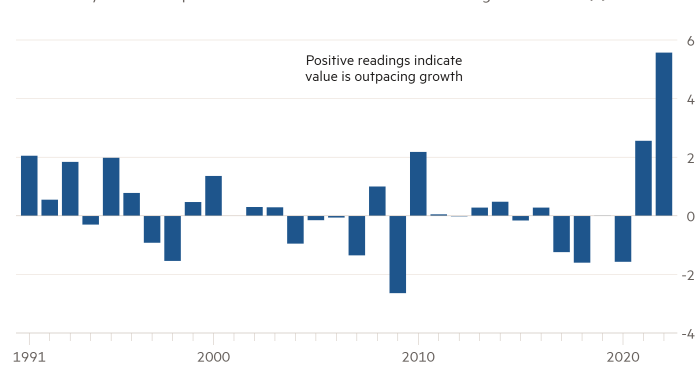

Value stocks have managed to eke out a gain in the first week of 2022 when the S&P 500 has fallen 1.9 per cent. In a sign of the strength of the market shift, the Russell 1000 value index has outperformed its growth counterpart by more than 5 percentage points this year, the most over the comparable period on records going back to 1991, according to Bloomberg data.

The fallow start for growth has been particularly painful for funds invested in riskier corners of the $53tn US stock market. Shares of lossmaking tech companies have fallen by roughly a tenth already this year while recent initial public offerings are off 12 per cent, according to closely followed indices collated by Goldman Sachs. The bank estimates that companies that have generated strong growth regardless of the ups and downs of the US economy have declined more than 8 per cent.

Fidelity Investments’ Timmer said this kind of rotation is a “familiar story”.

“It happened in the late 1960s with the speculation on space and tech stocks. It happened in 2000 . . . and usually the Fed plays a role because it is that segment of the market that suffers,” he said.

One reason the market move has been so intense is because many mutual funds and hedge funds were holding concentrated positions in many of the same companies, analysts said.

“You have everyone trying to hit the exit at the same time,” the head of equities trading at one New York-based bank said. “Normally in a healthy market when hedge funds are unwinding, mutual funds try to come in and buy weakness and it has the effect of stabilising. But now . . . when hedge funds and pension funds start to unwind risk, mutual funds are going in the same direction.”

The rotation has also been confounding at times, with competing forces pushing and pulling investors in opposing directions and muddying the narrative for the market’s moves. And investors have been given a taste for shortlived rallies in value stocks before, including at one point last year.

It points to a bumpy road ahead, with rises and falls in rates colliding with concomitant threats of coronavirus to the economy.

“While I think the market can and will go higher, investors will need to navigate these rotations,” said Russ Koesterich, a portfolio manager at BlackRock. “Investors are partly taking their queue from the bond market and the part of the market most susceptible to those moves in rates are the speculative tech names.”