The global warming effect of record production in the Permian Basin, the world’s biggest oilfield, has drawn fresh scrutiny as methane spews into the atmosphere from its oil and gas operations.

The region’s emissions of methane, a potent greenhouse gas, have come back into the spotlight as production rebounds to match the oil price surge from the depths of the 2020 crash.

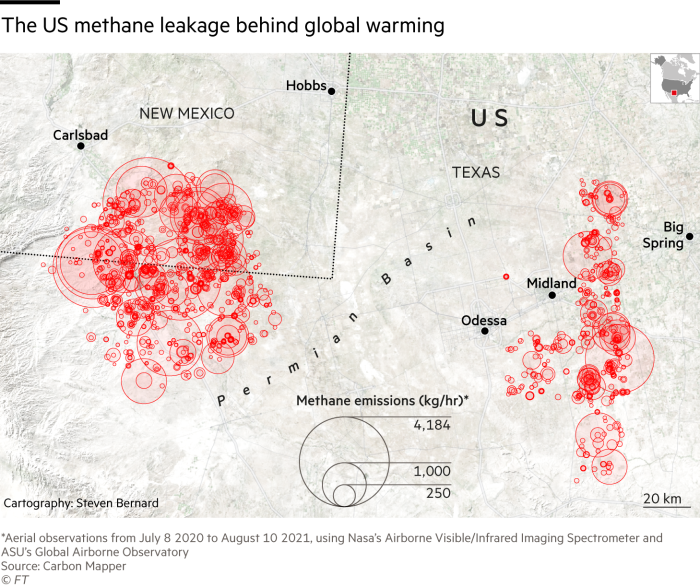

New research has found that large sources of these emissions can be traced to a small handful of leaky pipes, wells and plants. Just 30 facilities across the Permian account for about 100,000 tonnes of methane emissions each year, according to aerial data collected by the Environmental Defense Fund and Carbon Mapper.

That is roughly the equivalent the near-term pollution of half a million cars, or about 1 per cent of all methane emissions from the oil and gas sector in the US, according to Environmental Protection Agency figures.

Tackling methane emissions is seen as critical to limiting global warming, as it has 80 times the warming potential of carbon dioxide over a 20-year period. A UN report last year identified the reduction of methane emissions as the quickest way to slow the heating of the planet.

The main sources of human-caused methane were agriculture and waste dumps while fossil fuel extraction produced about a third of the pollution, the report found.

“Mitigating methane emissions now is the biggest down payment we can make on minimising impacts of climate change,” said Riley Duren, chief executive of Carbon Mapper and a research scientist at the University of Arizona.

“And the oil and gas sector is the most shovel ready sector for action: it’s all human infrastructure and most of the technologies required to mitigate emissions are well understood.”

The Permian Basin covers an area the size of Britain and straddles West Texas and Southeastern New Mexico. It accounts for two of every five barrels of oil pumped across the US.

Output slumped in the wake of the 2020 oil price crash but the oilfield is now pumping more oil than at any point in its history. In February it will produce more than 5m barrels of oil for the first time, according to the US Energy Information Administration.

The prolific nature of the Permian makes it a key contributor to global methane emissions. According to a recent scientific paper, around 2.7m tonnes is released into the atmosphere each year from leaks in pipes, wells and processing stations across the basin, as well as from the intentional flaring of excess natural gas.

Efforts to tackle methane pollution have been at the heart of Joe Biden’s climate agenda. His administration has reinstated rules on plugging leaks in new oil and gas facilities that were scrapped by Donald Trump. New regulations put forward by the Environmental Protection Agency would also clamp down on leaks by existing facilities.

US special envoy for climate, John Kerry, this week hosted a gathering of ministers from more than 20 countries that also discussed national blueprints for how to cut methane emissions. More than 100 countries agreed at the COP26 climate summit in Glasgow to reduce emissions from methane by 30 per cent by the end of the decade compared to 2020 levels.

The methane crackdown has been broadly supported by most big public oil producers in the Permian, who have come under increasing pressure from shareholders over their environmental credentials. But they are under pressure to live up to their pledges.

“There’s a very wide range of investments being made by companies to mitigated emissions,” said David Lyon, senior scientist at the Environmental Defense Fund. “[But] I don’t know if I would say any company is doing enough.”