The unprecedented economic sanctions imposed on Russia in response to its invasion of Ukraine represented a calculated risk. The US, the EU and other governments moved in the face of warnings that their actions could foul up the short-term lending markets that underpin global finance.

So far, the worst fears of market participants have not materialised. Measures of short-term borrowing stress have risen, but remain well below the levels of past crises, and Federal Reserve facilities set up during the pandemic to help foreign central banks access dollars have been little used.

While it was too early to give the all-clear, investors said the plumbing of global financial markets appeared to be functioning even as stocks and government bond yields fell and the price of oil and other commodities soared.

“People are nervous. People are scared right now. There is a scramble for funding,” said John O’Connell, a portfolio manager at Garda Capital Partners. “But I don’t think this will get out of hand.”

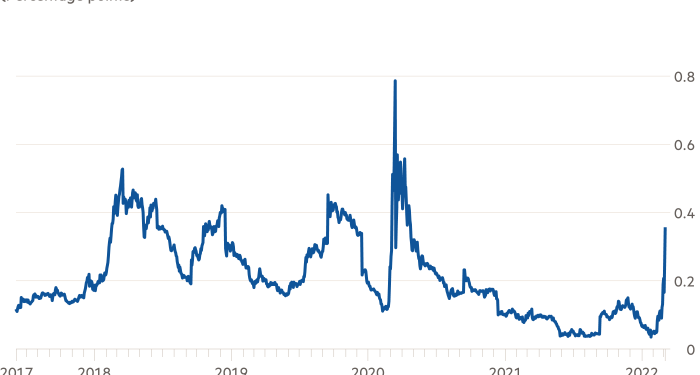

The state of play was highlighted by the movement of a measure of dollar-funding stress known as the FRA-OIS spread. It rose from 0.26 percentage points on Thursday to as high as 0.38 percentage points on Friday before dipping back to 0.35 percentage points.

That was its highest level since April 2020. But it was still well off its peak of nearly 0.8 percentage points in March 2020 or more than 2.1 percentage points during the 2008 financial crisis.

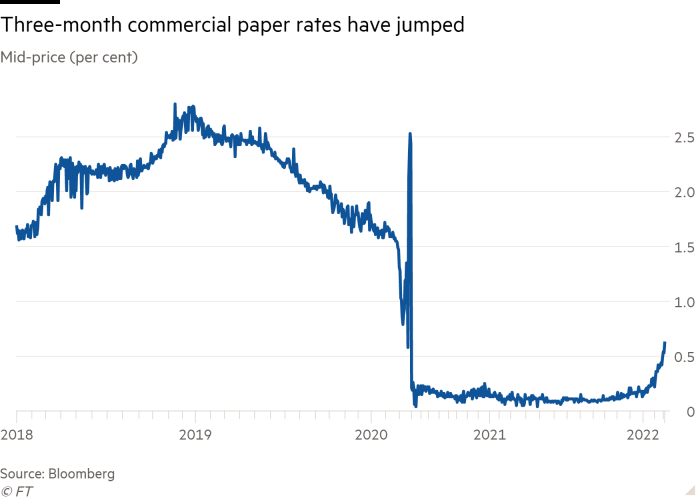

Rates on three-month commercial paper — which enable companies and banks to borrow from investors over short periods of time — also rose to about 0.6 per cent, but remained well below the levels hit when Covid-19 reached the US in early 2020.

Another positive indicator came from currencies such as the Mexican peso and South African rand, which would be expected to buckle in the event of a serious dollar-funding shortage. They have both been relatively stable.

Markets were put to the test as governments imposed sanctions on Russia’s central bank, constraining its ability to access roughly $630bn in foreign reserves, including dollars that it would normally be able to lend in funding markets.

Investors, bankers and analysts said the impact was mitigated by the existence of Fed programmes that were set up during the pandemic to keep dollar-funding markets operating.

The standing repo facility, made permanent in July, allows US banks to swap Treasuries for dollars. The Foreign and International Monetary Authorities (FIMA) facility affords that same privilege to foreign central banks. So-called swap lines allow foreign central banks to temporarily borrow dollars.

In a sign other countries were able to access dollars, no foreign central bank had tapped FIMA as of Friday, and the usage of the swap lines remains minimal.

When asked by US lawmakers on Wednesday about dollar funding markets, Jay Powell, the Fed chair, said they were “functioning well”. He said a “great deal of liquidity” was coursing through the system.

“Between our swap lines and our repo facility for other foreign central banks and our standing repo facility in the Treasury market, we have institutionalised liquidity provision,” he said.

Lorie Logan, an official in the markets group of the New York Fed, suggested in public remarks on Wednesday that the existence of these liquidity facilities was enough to ensure smooth functioning, even as usage remained low.

“Their presence has also provided confidence in available liquidity and that knowing these are operationally there and standing, I think that has mitigated some of the cautionary demand for liquidity that might have emerged amid the heightened uncertainty that has emerged in recent days,” she said.

Bankers also said they had been briefed in advance by Biden administration officials about the possibility of sanctions on the Russian central bank, allowing them to prepare for the impact.