These words, posted on a forum in 2009, were accompanied by a black and white image of school children, a vague but distinctly inhuman figure hovering in the background (see above).

The response was positive: on a thread dedicated to creepy photo edits, the combination of a vague but ominous caption and an even more nebulous photo edit made it a favourite among others who posted.

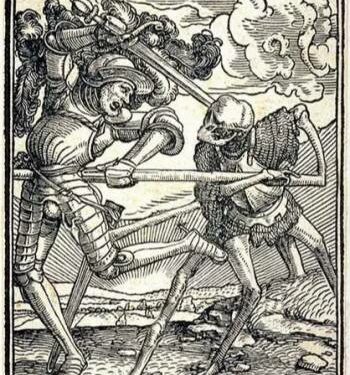

The mythos of the Slender Man, the name given to this figure on the forum, grew. Soon, other stories and pictures of the faceless humanoid emerged from different creators and on different channels. Its powers multiplied; later iterations often featured inky tentacles. And as the stories grew, so did the number of supposed victims of its attacks — though its choice of clothing, a G-Man-esque suit and tie, remained consistent across most accounts.

The idea that this would end up inspiring a real-life stabbing half a decade later would have seemed ludicrous at the time. But perhaps more disturbing is the fact that the evolution of the Slender Man mythos offers a model to understand how posts on digital platforms can lead to events ranging from a riot on Capitol Hill to Wall Street Bets’ ‘revolt’ against hedge funds. For all the talk of an enlightened age, myths can still impact how we live on a fundamental level.

Enter The Slender Man

The Slender Man is the most infamous example of a “creepypasta”, the internet’s folklore. The term derives from another internet colloquialism, copypasta, a derogatory shorthand for prose that is popularly copy and pasted across internet forums, sometimes as an inside joke. The creepy variety became a staple of the mid 2000s to mid 2010s, often spanning the gamut of unsettling short stories with echoes of Edgar Allen Poe, to terrifying and expansive visions of Lovecraftian horrors, to childishly grotesque tales rivalling the worst excesses of chain email. Some are ephemera on imageboards, while others — like the 13 year old SCP Foundation — have dedicated homes.

Creepypasta are more than just digitised versions of ghost stories though, says Joe Ondrak, a senior researcher at counter-misinformation group Logically, and a doctoral student studying the topic:

The nature of the platform also affects what you see, he says. What began as spooky photo edits with short captions ended up re-emerging in different forms and with different stories in web series, video games — and the inevitable livestreams of said games.

Just as important is the interplay between an in-group in the know and newcomers who don’t realise the joke is at their expense, says Ondrak:

And as those communities grow and ideas within them mutate, we see decentralised myth-making in action — the creation of communities, located around the world, connected not so much by a leader but through acts of content creation and consumptions.

The bigger picture

One of the great decentralised myth-making exercises in financial markets is the meme stocks rally. Though individual Redditors or Telegram channel owners played a part, the idea that it was a revolution of the common folk against greedy hedge funds and the powers that be was spread and evolved by regular users.

QAnon, superconspiracy of the year 2020, furnishes us with a prime political example. The anonymous poster at the heart may have produced the Q drops — ‘clues’ in the form of tedious nonsense, links to YouTube videos or stock photos — but it relied on a community of self-described truth-seekers to study these ideas and create the dense, ludicrous and often inconsistent ideology that has emerged.

Decentralised myth-making reflects the ambivalent power of the internet as a grand collaborative tool. It is not so much the death of the author — those who create the concept can continue to act as influencers. But it does offer a much broader view on who gets to shape the meaning of a movement.

From digital to analogue

Though talk of myths may seem inappropriate for an enlightened age, the reality is that online ideas have offline power. Hyperstition — the reification of fictions — is a slippery slope, admittedly. Take it too seriously, and you end up promoting ideas like “meme magic”: a nonsense belief that the power of the alt-right’s memesters helped propel Donald Trump to victory in 2016.

“A lot of that meme magic stuff overdetermined the power of online culture and separated it out as if the things that were being expressed were coming out of a poisoned well online rather than being reflective of broader societal belief systems,” says Jessica Beyer, a lecturer at the University of Washington who has written extensively on internet culture.

But she emphasises that the line between the online and offline worlds is hardly impermeable. Decentralised myth-making has already had real world consequences. Some, in the case of Wall Street Bets and the meme stock rally, are relatively benign.

Others, less so. In the case of QAnon, decentralised myth-making has led to a litany of threats, protests, kidnappings and even murders. As for the Slender Man, 2014 saw a series of attacks blamed on its inspiration, including the attack by two Wisconsinite teens on a friend in order to become the creature’s “proxies” on earth.

“Are people colluding? Probably not. But they are all impacted by this meme in the same way, and decide to do something in the same way,” says Aaron Trammell, assistant professor of informatics at UC Irvine. “It’s a shared motif, a shared mood.”

Trammell sees more of a line between the chaotic and freeform act of play and more ordered myth-making, though:

The future of creepypasta

The Waukesha stabbings were a turning point for the Slender Man, leading to a transformation from internet folklore into a public threat. But creepypasta more generally were hit by the change of attitudes post-2016, says Ondrak, as public sentiment darkened on platforms and the media. Though new content still appears in subreddits like r/nosleep, he says there’s been an uptick in horror fiction from known authors, who use the conceit that what they’re describing is real.

In investment circles, though, the financial counterparts to creepypasta still abound, encouraging readers to commit to penny stocks, unregulated products and, yes, crypto. The villains in their stories may be even more nebulous than the Slender Man, but their threats of certain doom for the unwary can be just as powerful. (NGMI! HFSP! Etc!) The besuited baddie might have an ill tally to its name, but far more have been duped into reckless investments than have fallen prey to its lure.