The cost of food commodities that make up a typical breakfast has soared to its highest point in a decade under the strain of bad weather and supply-chain crunches, providing another in a long list of upward pressures on global inflation.

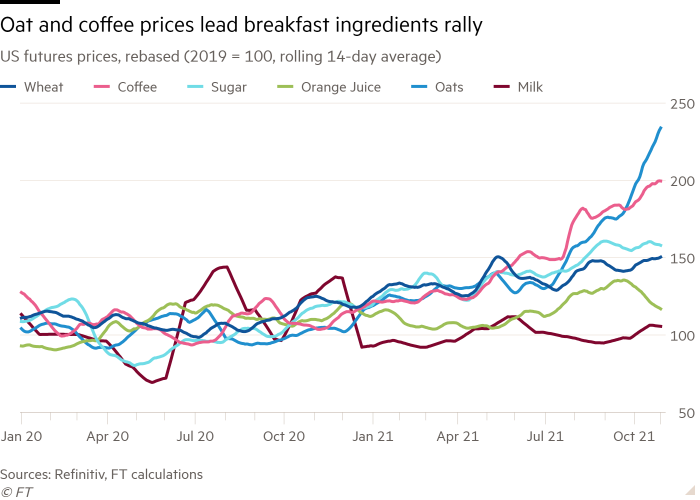

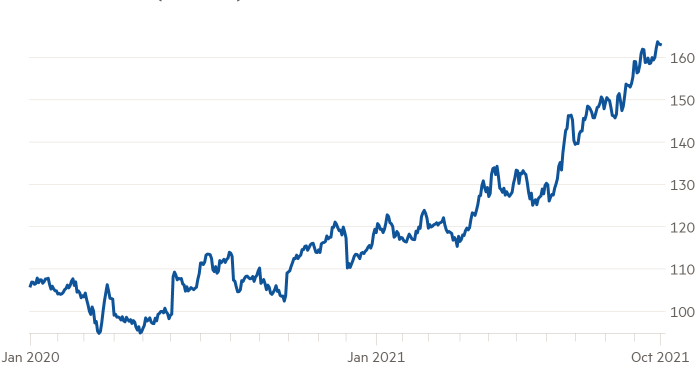

The Financial Times breakfast indicator, based on futures prices for coffee, milk, sugar, wheat, oats and orange juice, has shot up by 63 per cent since 2019, in a move that has accelerated since this summer.

Food companies are raising prices for consumers to protect their profit margins, with large multinationals including Nestlé and Procter & Gamble warning over the past few weeks that cost pressures will continue to worsen before they get better. Analysts warn that higher costs for production, processing and transport will keep prices elevated.

“High prices are here for at least another year,” said Carlos Mera, head of agri commodities market research at Rabobank.

Benign weather and bumper crops between 2016 and 2020 meant that prices for food commodities were largely subdued, but since then various problems have struck at once, said Will Osnato, analyst at commodity data and research firm Gro Intelligence.

Problems in producing food have collided with higher demand, as the rebound from the pandemic proved to be stronger than most people had predicted. The switch from “just in time” procurement to “just in case” buying has also pushed up extra demand for wheat, coffee and sugar. “Total worldwide demand is running higher than anybody thought,” Osnato said.

Although prices for food commodities tend to settle in the last few months of the year as it is post harvest season in the northern hemisphere and the start of the growing season in the south, prices have continued to rally this year, with breakfast commodities up 26 per cent since the halfway point.

Weather patterns are contributing. Forecasters are predicting a La Nina weather event for the second consecutive year, lining up another period of droughts and frosts. The cost of fertilisers, which are made from natural gas, has surged as many manufacturers have also stopped their plants because of soaring gas prices, adding to the strain.

In a year of extreme weather, growers in key producing regions of many food commodities faced output declines. Wheat futures prices are up 20 per cent from the start of the year as Russia, North America and Argentina were both affected by drought, while European producers were hit by rain. The last time wheat prices soared to current levels was in the aftermath of the 2012 drought in the US.

Oat prices, meanwhile, have doubled this year after a severe drought in Canada wiped out almost half of its crop. As the world’s largest oat producer and exporter, Canada’s oat production drives global trade, and this year its crop shrank 44 per cent, according to Gro.

Drought in Brazil, the large producer and exporter of sugar and coffee, has hit both commodities. Sugar is up 26 per cent since the start of the year, while coffee has jumped 56 per cent. Farmers in the largest coffee growing regions were also hit by unseasonal frost in July, which damaged many trees, raising fears for the next season’s crop.

Coffee has also been one of the commodities most affected by the container disruption, said Mera. Shipping continues to be a problem affecting the supply chain, with container rates almost 280 per cent higher than last year, according to shipping group Drewry.

Many of the hedging contracts that large roasters have are expected to terminate at the end of the year. François-Xavier Roger, chief financial officer of the world’s coffee roaster Nestlé, said earlier this month that coffee prices for customers would increase next year, “because this is really when we will start feeling the pressure on input cost inflation by category”.

Firm demand has driven prices higher for milk and orange juice, which saw an initial pandemic boost, and have continued to be supported by the rise of consumers eating breakfast at home. Rising biofuel demand is also pumping up prices for vegetable oils, such as canola, soya oil and palm oil.

Higher prices typically cut demand while encouraging increased production. However, the adjustments may be slow this time, warn analysts. “There are no signs of that at the moment. There’s certainly a dislocation,” said Amy Reynolds, analyst at the International Grains Council.

‘Just in case’ demand is continuing and poor harvests in developing countries are leading to a rise in grain tender prices. “There’s no sign of demand destruction happening despite the level of prices. How high do prices have to be?” Reynolds asked.

The rise in costs for farmers will make it difficult for them to capitalise on the higher prices and increase supplies.

“All agricultural commodities are going to be affected by fertiliser prices not coming off in the short term,” said Kona Haque, head of research and trading firm ED&F Man. The severe droughts this year mean that many farmers may not have had the harvest to benefit from the higher prices. This will hit the amount of seeds, fertilisers and pesticides they can buy for the next season, she added.

Even if a stroke of luck brings exceptional weather conditions and bumper crops over the next year, it will not be enough to replenish inventories and bring down prices to previous levels, say analysts.

“It’s going to take more than a year to grow your way out of the tight supply situation we are in now,” said Osnato at Gro.