Worries over deeply entrenched structural issues in China’s $21tn debt market are keeping foreign investors at bay, even as Beijing prepares to grant unprecedented access to local currency bonds.

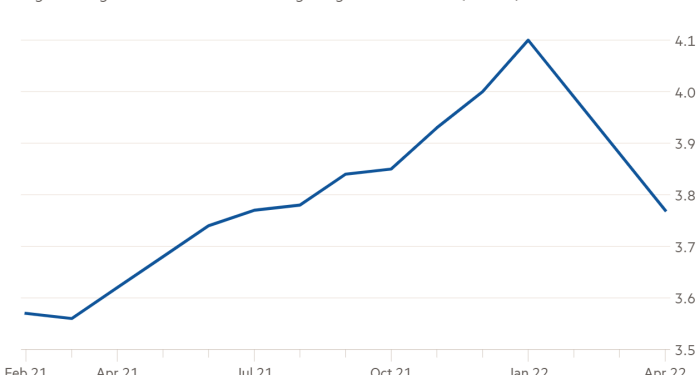

Global fixed-income traders sold about$35bn worth of renminbi-denominated bonds in the first four months of this year, and many are warning that the outflows will only get worse as concerns grow about poor liquidity — the ability to buy and sell the debt easily — and the country’s opaque process for resolving defaults.

The pressure on China’s bond market comes after years of steady international buying and despite the government’s efforts to boost demand for domestic corporate debt through an upgrade of Hong Kong’s Bond Connect programme at the end of this month.

Asset managers say the key to improving sentiment would be for Beijing to make difficult and long-delayed market reforms, such as more transparency on how defaults are handled.

“Access is no longer a problem,” said Jenny Zeng, co-head of Asia-Pacific fixed income at AllianceBernstein. Enhancing foreign access to onshore credit was a “good gesture”, she said, but it “doesn’t change some of the structural, more long-term problems” that keep foreign investors from pumping more money into Chinese bonds.

Missed payments, in particular, have become an issue of priority after the high-profile default of China Evergrande, which shook the domestic property sector and weighed more broadly on economic growth.

“If the default resolution process becomes more transparent and institutionalised, that can be a big supporting factor for us to allocate more money into China,” Zeng said. “Anything that’s predictable, logical — we can price that.”

China’s debt markets have also been hit by Covid-19 lockdowns that have weighed on the renminbi’s exchange rate. At the same time, US Treasury yields have risen as the Federal Reserve tightens monetary policy aggressively — a move that has wiped out China’s advantage as a more attractive home for bond investors.

“The key going forward is not so much access but investors’ confidence,” said Wang Qi, chief executive at fund manager MegaTrust Investment in Hong Kong. Wang said recent defaults by Chinese real estate developers “do not give foreign investors confidence in the onshore bond market”.

The default by Evergrande, which has more than $300bn in total liabilities, began in September last year but took months to be formally declared, and has been mired by a lack of disclosure about the company’s plans for restructuring. Foreign investors in particular have been concerned that onshore bondholders will be favoured at the expense of offshore creditors.

“We’re not scared by the default itself,” said Zeng, adding that prioritising onshore creditors would not be a problem if the rules were clear in advance.

“The challenge there is that the resolution process is less predictable, and therefore it’s more difficult to price the default.”

Traders must also grapple with a lack of liquidity in China’s debt market, which is dominated by state-run financial institutions that typically buy and hold bonds to maturity. It also has a limited number of market makers, which can make for choppy trading as buyers struggle to match up with sellers.

“China’s bond market is still dominated by banks,” said Ivan Chung, an associate managing director at Moody’s Investors Service. Chung said that despite some improvement in recent years, commercial banks still held about 65 to 70 per cent of China’s corporate bonds, with insurers and investment firms accounting for another 20 per cent.

“On a selective basis, there is some liquidity,” he said, “but obviously there’s room for development.”

International investors said one of the most immediate ways to help address the risks posed by such shortcomings would be to grant access to renminbi bond futures, as that would allow them to hedge their risks as well as make leveraged bets on Chinese debt.

But authorities’ recent changes have intentionally excluded any measures opening up futures and similar assets to foreign investors, as that might allow them to profit from a sell-off, according to a Shanghai-based senior investment manager at one European lender.

“Regulators do not fancy the idea of letting foreign investors short [bet against] China government bonds,” the investment manager said. The person added that domestic investors with massive government bond holdings, such as state-run lenders, were also banned from making leveraged bets on Chinese debt since “the only direction of their trades would be to sell, which would cause a meltdown in the market”.

That leaves policymakers with few easy options when picking where to start the next wave of bond market reforms. But as China grapples with an economic slowdown, it may have little choice but to make hard decisions on how to handle mounting defaults.

Chung said rising defaults were “of course not good for investors” but added that recent developments would ultimately help to differentiate the risk levels of onshore bonds.

“Five years ago, investors would panic if the bond they held defaulted,” he said, whereas now they have at least a few options to try to limit losses, including negotiations with bond issuers.

Even so, Chung did not expect inflows to resume in the coming months simply because China grants easier access to its exchange bond markets.

“The key is whether investors see appealing yields in the Chinese onshore market,” he said.