The soaring price of fuel threatens the airline industry’s recovery just as passengers are returning to the skies.

As crude prices remain elevated, airline bosses face a critical calculation: how much of their fuel bill can they pass on to customers without leaving their planes empty?

The heads of Europe’s biggest airlines met in person for the first time in two years this week at a conference in Brussels, each reporting a burst of demand as pandemic-related travel restrictions are rolled back.

Lufthansa’s chief executive Carsten Spohr said his airline would fly more short-haul routes this summer than in 2019, while British Airways owner IAG plans to return to pre-pandemic levels of transatlantic flying by the summer.

Leading the pack, Ryanair expects to fly 165mn passengers in this financial year, which began in April, up on 150mn before the pandemic.

“There’s big pent-up demand for the summer, there is just no doubt about that,” said easyJet’s chief executive Johan Lundgren.

But the price of fuel — which can make up as much as a third of an airline’s costs — threatens the profitability of this rapid recovery.

Jet fuel has risen by a third to more than $150 per barrel since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine plunged commodity markets into turmoil. The rise to 14-year highs has outpaced even Brent crude, as airlines have been forced to pay a premium for the refined product.

US airlines have already indicated they will pass on the fuel costs to consumers, betting that passenger demand is robust enough to withstand it. Delta, for example, has said it needs to recoup between $15 and $20 each way on an average ticket value of about $200 to offset higher fuel costs.

Some airlines have introduced fuel surcharges, which are treated like government taxes that make new tickets more expensive and appear as extra charges when redeeming air miles. Air France and KLM have said long-haul flights will get more expensive. A KLM return flight from Amsterdam to New York will rise by €40 in economy class and €100 in business.

Spohr of Lufthansa was unequivocal that airlines needed to “make sure our business model still works” in an environment that also included higher airport and staff costs. “Inflation eventually hits every industry,” he said.

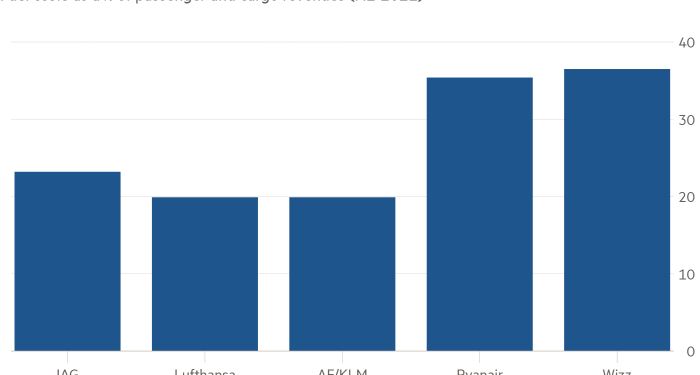

Low-cost airlines are particularly vulnerable as fuel costs make up a higher proportion of overall ticket prices than their full-service competitors, which charge more for seats.

As higher inflation, including soaring energy costs, hits European consumers, travellers hunting for cheaper flights are likely to be more cost-sensitive, making it difficult to raise prices without hitting demand.

EasyJet’s Lundgren said that “inevitably” airlines would have to bear some of the costs themselves, but added the deep cost cuts forced on the aviation industry by the pandemic would help cushion the blow.

“We’re always got to make sure that we can offer really, really attractive fares for passengers. And pricing is super-dynamic,” he said.

Demand for travel this summer was strong, but outside of these peak periods customers still needed enticements, said Ryanair boss Michael O’Leary.

“I am sad to report that currently at Ryanair, ticket prices are falling in April and May, they are softer than in 2019,” he said. “We are still trying to build back our forward bookings into the summer.”

Ryanair is better protected than most, and has hedged 80 per cent of the fuel it expects to need this year at about $65 per barrel, a “fortuitous” decision that would help the company swing back into profit, said O’Leary.

Low-cost rival Wizz Air, whose shares have tumbled almost 40 per cent this year, was unhedged when the war in Ukraine began, but reversed course and bought protection in March after the spot price had already soared.

Asked whether the spike in oil could turn out to be a surprise competitive advantage for Ryanair, O’Leary said his airline’s growth was constrained by the number of new deliveries arriving from Boeing.

But he expected it to drive home his “cost advantage” as the industry recovered.

AirBaltic’s chief Martin Gauss said airlines could not think in terms of just “passing” costs straight to consumers without taking into account prices on other airlines.

“The market basically decides on the ticket price . . . If the market is not increasing prices then the higher fuel price just means you are either not taking passengers because you are not selling at the right price, or you are taking a higher loss,” he said.

Robert Boyle, a consultant and former head of strategy at IAG, said Ryanair could take advantage of its hedging position and strong balance sheet to keep ticket prices low and squeeze its competitors.

“The Ryanair factor is going to make it hard for other airlines to raise prices without seeing a big hit to demand,” he said. “If they do it anyway and just cut more capacity to absorb the volume loss, they will be ceding even more market share to Ryanair. It’s going to be a tough few months.”