Mark Weidemaier is professor of law at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; Ugo Panizza is professor of international economics at the Geneva Graduate Institute and vice president of the Centre for Economic Policy Research; Mitu Gulati is professor of law at the University of Virginia.

We are a bit obsessed with sovereign guaranteed bonds, such as the one issued by SriLankan Airlines and guaranteed by its government owner. This one is a humdinger.

Guaranteed bonds are a puzzle. One might assume they would carry a lower interest rate than the government’s own bonds. That’s because they are backed by both the issuing entity and the government itself. Even when the issuer is poorly-managed and haemorrhaging money, its guaranteed bonds would seem no worse than the sovereign’s own. Yet guaranteed bonds often carry a higher interest rate, possibly because they are less liquid than standard government bonds.

Even for supposedly safe instruments, there is a premium associated with plain vanilla government bonds vis-à-vis guarantee bonds. Things become even more interesting for riskier bonds because in a sovereign debt restructuring, guaranteed bonds can introduce complications. Many complications.

Although the guarantee can be written so that it can be restructured along with the sovereign’s other obligations, this rarely happens. On the contrary, guarantee contracts often seem designed with little thought about what will happen if the government gets into distress and needs to reduce its obligations. So holders of guaranteed bonds sometimes escape the restructuring completely.

Is there a poster child for a badly-designed government guarantee slapped on bonds issued by a money-incinerating company? Before Sri Lanka, we would have pointed to the Greek railroad bonds issued before the Greek debt crisis from a decade ago.

Those bonds were such a hassle to restructure that the Greek government did little more than politely ask bondholders to take haircuts along with the government’s other creditors. Unsurprisingly, the answer was generally “no thanks, we’d rather get paid in full.” Holders of bonds issued by the loss-generating Greek railway not only got their regular interest payments, they got paid in full. Sovereign Greek bondholders . . . well, not so much.

But SriLankan Airlines may now take the cake. Not so long ago, the company was profitable and (as one of us recalls) pleasant to fly. But the ruling family decided that it could run the airline better on its own. Now, the airline loses about $100mn a year; and it has incurred a net loss every year since 2008. Reports indicate the government wants to privatise it, but there are few takers. The government not only ran the airline into the ground, it supported its borrowing on the international debt markets with government guarantees.

And that brings us to the crux of the story. The SriLankan Airlines guaranteed bond is a veritable nightmare for a debt restructurer.

Nightmare contract terms

The modification term is the most important provision in a distressed sovereign bond. This term is often referred to as a Collective Action Clause, or CAC, because it enables collective decision making by dispersed creditors.

The CAC sets out the requirements for holding a vote to reduce the sovereign’s payment obligations. What fraction of creditors must vote to approve the restructuring plan before it binds the entire group? If they hold bonds, can the government and affiliated entities cast votes? If the sovereign has multiple series of bonds outstanding, is the vote aggregated across the different series, or is it taken series by series? The CAC answers these and other questions.

That last question, the question of aggregation, is especially important for a country like Sri Lanka, which has a large debt stock represented by multiple series of bonds. If it must hold restructuring votes series by series — for example, persuading 75 per cent of each bond to vote in favour — then it becomes vulnerable to holdouts. This is especially true for smaller bonds, where a blocking position is easy to obtain.

When the vote is aggregated across series, it becomes significantly harder to buy a blocking position. The Greek restructuring of 2012 highlighted the importance of aggregated voting. Greece attempted series-by-series restructurings in thirty-some series of bonds, but holdouts blocked the restructuring in about half of the bonds. These bonds were paid in full, although Greece’s other bondholders took brutal haircuts. As a result, beginning in 2014, sovereign bonds began to include aggregation features.

For whatever reason, Sri Lanka came late to this party, but finally began to include aggregation features in its sovereign bonds starting in 2018. The guaranteed airline bond was issued in 2019 yet, inexplicably, it does not include the aggregation feature. Instead, it uses an antiquated CAC template that we’ve only seen a handful of times in all of our research on sovereign bonds.

Given the relatively small size of the airline bond —$175mn, as compared to sovereign bonds that often exceed $1bn — the absence of aggregation features is especially striking.

Consent to exit?

Typically, bonds without aggregation features can still be restructured in a fashion that deters holdouts. This involves a technique called the Exit Consent. Here, the sovereign takes advantage of the fact that, although the CAC often requires a creditor supermajority to modify payment terms, it can modify less important terms with the support of only a bare majority. But these less important terms can still be quite significant.

The idea is that, when a majority of creditors support the restructuring, they can threaten to leave prospective holdouts with bonds that have had key features removed or amended (eg, a cross default clause). Holdouts do not always fall for the threat, but Exit Consents can be an effective restructuring tool.

Bizarrely, the Sri Lankan airline bond seems to require the same vote to change both important terms and less important terms (75 per cent in both cases). To be clear, the bond does distinguish between important and less-important terms. It does this by specifying a higher quorum for meetings to amend important terms. But this difference is unimportant; what matters is the vote itself.

Why in the world would one design a bond modification provision that distinguishes more from less important terms but then requires the same vote to change them all?

See you in Colombo

As if that’s not weird enough, the prospectus for the airline bond seems to require a restructuring vote to occur at a meeting, while most sovereign bonds allow for written votes.

We think of the option to hold an actual meeting of bondholders to vote on a restructuring proposal — still found in many bonds today — as a quaint holdover from the days before easy travel and instantaneous, reliable methods of communication. Then, a meeting may have been necessary to make an effective, collective decision. But in the modern world, it is utterly bizarre to require a vote to be taken at a meeting.

We know that deal documents often begin with a template used in a prior deal. But this usually means the deal from the prior week, not the prior century.

The strangeness continues. Sri Lanka’s international sovereign bonds are governed by the law of New York state and provide for jurisdiction in New York courts. The airline bond is governed by English law and gives jurisdiction to an arbitral tribunal. Again, why?

The more different this bond is from all the others, the harder it is to wrap it into the same restructuring. And because the government seems to have procrastinated in hiring restructuring advisers, there will be significant time pressure to design the restructuring. The airline bond may get paid in full simply for lack of time to design a clever method to restructure this odd little bond.

Some goofiness that favours the government

So, the terms that favour creditors are goofy, but there are also glitches on the other side. Here’s one: The offering circular for the airline bond says that it is guaranteed “by the Government of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka.”

Isn’t that weird, you might ask? There is a potential difference between the government and the state itself (the latter being the “Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka”). Now, the offering circular is just a sales document, but if the language is used in the underlying contracts, it creates uncertainty about who the guarantor really is.

This might seem far-fetched, but Russia made a similar argument in 2004 regarding a guarantee made by the “government of the Russian Federation.” The case made it to the US Second Circuit, where a three-judge panel took the argument seriously enough to write a lengthy opinion. Russia lost. But remember, the airline bond is governed by English law, with disputes to be resolved in arbitration. Hmmm.

On balance, however, the goofy aspects of the airline bond seem to favour creditors. If some set of hedgies decide to target this bond and acquire a 25 per cent stake (remember, it is just $175mn and trading at XX), it is going to be awfully hard to cajole them into taking a haircut.

What about prices?

Might these odd features of the SriLankan Airlines bond reflect intentional, careful design? Perhaps the intent was to make the bond hard to restructure, thus assuring investors a higher payout if a restructuring did become necessary. Maybe.

But if this were the case, we would expect the airline bond to carry a lower interest rate at issue than a comparable government credit with the easier-to-restructure contracts. As it turns out, the guaranteed bond was issued literally within days of the sovereign issuing a debt instrument with the same maturity in 2024. Guess what? The airline bond carried a rate 65 basis points higher, not lower.

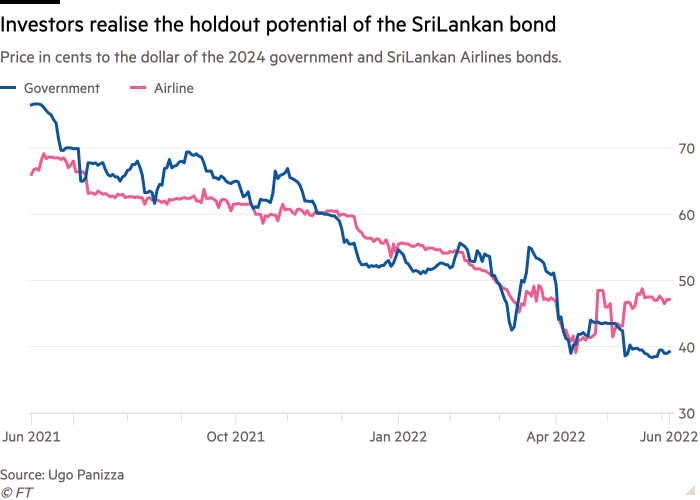

But what about now that it is clear Sri Lanka will have to do a serious restructuring? Have the hedgies figured out which bonds to favour? They have!

Here is a chart shows the evolution of the price for the airline Eurobond and a sovereign eurobond maturing a few days apart. We see they trade pretty much evenly until late April-early May 2022, when the light switch goes on and the airline bond jumps up above the sovereign one and, as of pixel time, has stayed there.

Time will tell whether Sri Lanka’s restructurers figure out a special strategy to deal with the guarantee or whether it pays out like those Greek guarantee bonds — in full and on time.