Bank of America strategists are not especially bearish on corporate bonds, as a general rule. With BOA #2 in the league tables for investment-grade debt, why would they be?

So we were intrigued by a small exercise in lede-burying this week, found in a Wednesday note about second-quarter earnings.

Hidden below near-useless metrics like gross leverage (down) and slightly-more-useful gauges of earnings growth (Ebitda up nearly 9 per cent), there was another figure that caught our attention: A record-setting drop in the amount of cash held by companies with investment-grade ratings, excluding financials and utilities, whose cash levels are contingent on regulator requirements.

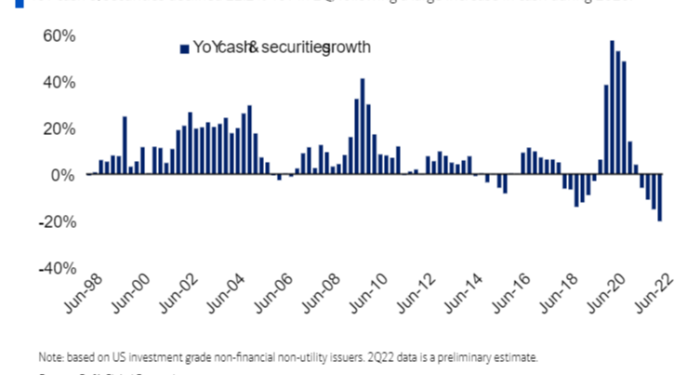

To elaborate, the amount of cash and liquid securities held by those corporate borrowers slid more than 20 per cent from last year, accelerating from a 15+ per cent drop in Q1. That is the quickest pace on record going back to 1998, the bank found.

Cash levels also fell on a quarterly basis, down 4 per cent from the prior quarter, compared with a historical average increase of 1.7 per cent in Q2.

(To be fair to the analysts, the note’s subject line includes the phrase “cash burn accelerates”. But there’s no mention of a record until halfway through the note, and the bullet-point summary only addresses the decline in gross leverage, which is, again, almost useless.)

There was a lot of talk about corporate cash liquidation back in 2018, when the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act changed the way multinationals’ foreign profits were taxed. Companies drew down their cash balances at a max 14 per cent yearly pace after that change in policy, and have already had two quarters of faster liquidations than that.

While the speed of the drawdown could simply be companies unwinding the record-setting cash hoards built up during the pandemic, it is also possible that near-double-digit inflation discourages cash accumulation even more than tax reform. (Albeit raising everyone’s cost of living in the process.)

This does raise the question of where all of this cash is going, however. The cash drawdown is especially puzzling if we assume that a significant amount of cost inflation is being passed through to the US consumer, which sounds reasonable given the ~9 per cent YoY increase in Ebitda cited by Bank of America.

Oxford Economics answered that question in an Aug. 11 note. The research firm found that for S&P 500 companies, a “significant proportion of the cash appears to have been used to fund record share buybacks, and we see these moderating now that cash balances have returned to more normal levels.” (The Inflation Reduction Act’s 1 per cent excise tax on buybacks may have something to do with it as well.)

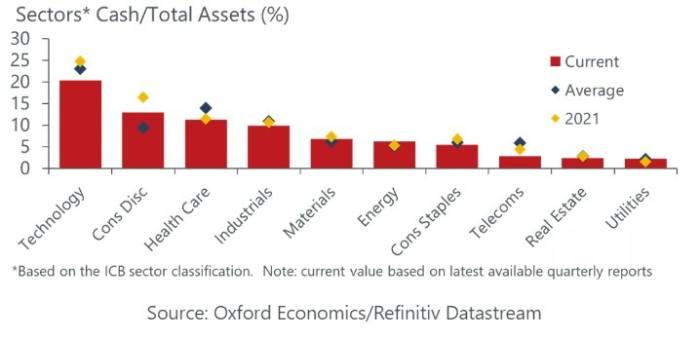

Technology and consumer discretionary sectors saw the steepest declines in cash, according to the firm, but companies in those sectors still have more cash, on average, than others.

The bigger risk comes in the consumer staples and telecommunications sectors, in Oxford Econ’s view. Cash holdings of companies in those sectors have declined below long-term averages.

“This drawdown is arguably a natural response to higher inflation which erodes the value of cash holdings,” the firm wrote, “but it does mean that companies now have less of a precautionary buffer as activity slows and financial conditions tighten.”

Financial conditions have become less tight in recent weeks, by Goldman Sachs’ measure, because of gains in equities and declines in long-dated Treasury yields. But lower long-dated yields also coincides with a steeper 2s10s yield curve inversion, a popular recession indicator. So some corporate caution may be warranted.