When he is not regaling us with daily tales of shrubbery thefts, a medley of injuries, golf and some markets, Jim Reid writes Deutsche Bank’s annual Default Study. The 24th one just landed in FT Alphaville’s inbox, and, as ever, it makes for interesting reading.

First of all, it is remarkable just how tranquil a period it has been for corporate debt.

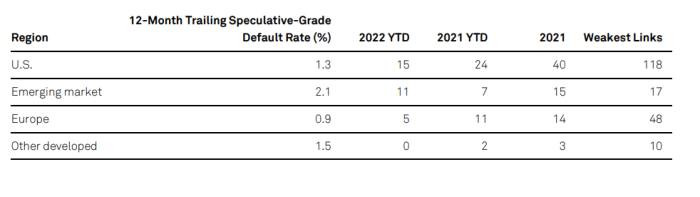

Last year saw one of the lowest junk bond default counts in a decade, and despite the recent market jitters, only 31 companies have defaulted globally this year, the lowest run rate since 2014 according to S&P Global. Even the rolling default rate of uber-junky triple-C rated US companies is the lowest it’s been for nearly four decades, according to Deutsche Bank.

The reality is that aside from a few notably awful spells in the immediate aftermath of the Covid-19 outbreak and the 2008 financial crisis, it’s been a pretty great two decades for corporate debt, with defaults trending lower and lower.

But Reid now sees a regime change lurking.

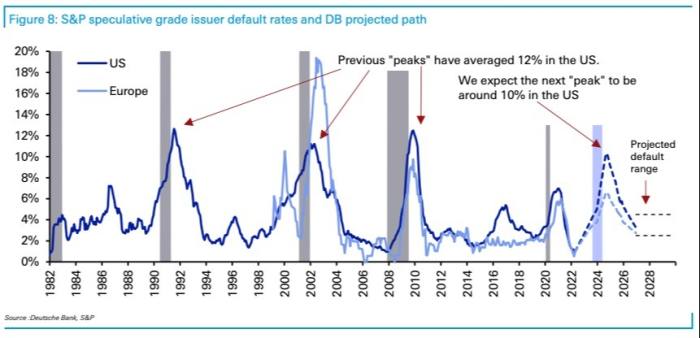

The “good” news is that Reid doesn’t think creditpocalypse is already upon us, as some have fretted. DB forecasts that the overall US junk bond default rate will climb to 5 per cent by the end of 2023 — the year it expects a recession to start — before peaking at 10.3 per cent in 2024.

The default rate for top-tier junk bonds (rated double-Bs) will only peak at 2 per cent, but Deutsche Bank thinks almost half of all triple-C bonds will end up in default.

Defaults will then moderate, but more slowly than has been the norm over the past two decades, and remain elevated at around 4-5 per cent by the end of 2025, DB predicts.

Europe will probably experience a notably less acute default cycle, with the default rate there climbing to 3.8 per cent by the end of 2023, peak at a more sedate 6.6 per cent in 2024 and then drift back to 2-4 per cent.

Defaults in emerging markets, meanwhile, are already on the rise. “Many issuers in the region have been able to pass through rising costs to customers — at least for now — though financing conditions are also tightening,” according to a report from S&P Global Ratings.

There are many reasons why Reid thinks defaults are likely to be structurally higher in the coming era, such as corporate profit margins becoming compressed.

But his central argument is that business cycles will become shorter than more volatile they have been in recent decades, as faster and more entrenched inflation limits how aggressively central banks can react to downturns.