The political debate continues to rage about the (de)merits of ESG, amid continued rises in oil prices — and sniping from Republican leaders such as Mike Pence. Check out my essay on this.

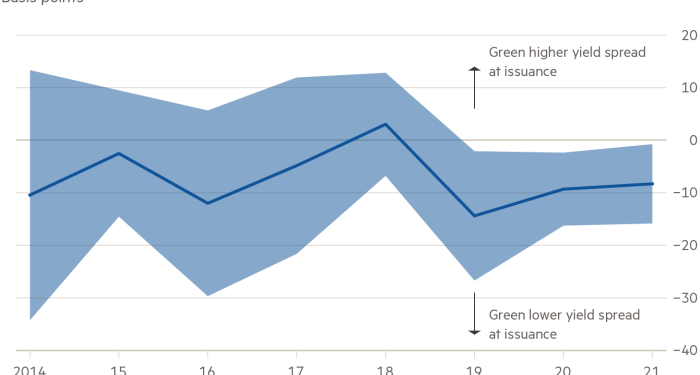

But irrespective of Washington politics, on Wall Street investors and issuers keep chasing “green” opportunities, out of self-interest as much as anything else. A new piece of research by the New York Federal Reserve provides one glimpse why: the Fed economists conclude that “on average, green corporate bonds have a yield spread that is 8 basis points lower relative to conventional bonds”. The report goes on to say that “this borrowing cost advantage, or greenium, emerge[d] as of 2019 [after] the growth of the sustainable asset management industry following EU regulation” — and a boom in investor demand.

That sounds encouraging for green evangelists. But there is a catch: “While green bond governance appears to matter for the greenium,” this rests on the credibility of the issuer, not the specific project — and it is the large developed market issuers that grab the real benefits. So does that mean that green bonds are just another establishment game? Let us know what you think — and check out the greenium chart below. Also read what John Browne, former chief executive of BP, laments about the past two decades of green activism. And Tamami reports on why Toyota’s bold electric vehicle claims are not all they might seem. (Gillian Tett)

What Big Oil did (not) do 25 years ago

May and June are the months when corporate grandees deliver commencement speeches to graduating students. And almost exactly 25 years ago John Browne, the former head of BP, did precisely that at his alma mater of Stanford University. His speech made waves: Browne told the students that it was time for fossil fuel majors to recognise the damaging pollution being caused by Big Oil, and prepare for a future based on renewable energy.

“We [at BP] have a responsibility to act,” he said, promising that BP would “monitor and control our own carbon dioxide emissions . . . and increase the level of support” for environmental research and the “transfer of technology . . . to limit and reduce net emission levels of greenhouse gases”.

Today, this sounds so commonplace that it smacks of platitudes. But in 1997 it was so unusual for Big Oil to make such statements that officials at the American Petroleum Institute accused Browne of treachery, creating years of bad blood. “Most of the oil industry objected to it very strongly,” Browne tells Moral Money.

So what should we conclude today? There are two ways to frame it. Green activists might view the 1997 speech as (yet another) reason to get angry; after all, if only Big Oil had acted back then to curb emissions — as Browne said they should — the world would not be facing such high risks of catastrophic climate change today. And while BP and Shell were admitting the problem then, they did not do nearly as much in subsequent years as activists such as Greta Thunberg would have liked. Worse still, other oil majors barely admitted that there was a problem at all.

However, another interpretation is that this 1997 speech reveals the degree to which the human zeitgeist can change — in surprising ways. Back then, Browne’s words shocked the API; today even Exxon and Chevron have embraced them in the face of spiralling oil prices and Republican party attacks on “woke” causes. “Industry and business as a whole now understands that something has to be done — you go against the grain if you say nothing needs to be done,” observes Browne, who (unsurprisingly) laments the fact this took such a long time to be accepted. And there is another reason for optimism, he adds: renewable energy has become cost-effective, due to widespread adoption and innovation, in a way nobody imagined in 1997.

That will not mollify green critics, who argue that BP (among others) is still moving far too slowly to embrace renewable energy, especially as it is enjoying record profits from oil price rises. Browne himself argued last month in an anniversary speech that “there can be no functioning economy without hydrocarbons . . . well into this century” and “the so-called energy trilemma of reliability, security and affordability is still there, even if most people had forgotten about security until recently”.

But Browne is also calling for measures to “reinforce the widespread and consistent use of ESG measures” and more investment in renewable technologies. And he is putting his time and money where his mouth is: he now chairs a fund led by Lance Uggla at General Atlantic to invest in renewable energy.

Is this too little, too late, from a Big Oil luminary? Or a sign of progress? Read the two speeches here and here, and let us know. If nothing else, it will provide source material for future (sustainability) historians about what could (and should) have happened 25 years ago. (Gillian Tett)

Toyota says it’s ‘serious’ about electric vehicles, but data says otherwise

Last month, I returned to Japan for the first time in two-and-a-half years, thanks to the Japanese government’s decision to ease its Covid-19 restrictions. Back at my parents’ home, where the television was seemingly always on, one advertisement caught my attention.

In the Toyota TV spot, the carmaker’s boss, Akio Toyoda, tells a popular Japanese actor, Teruyuki Kagawa: “Toyota is serious about BEV [battery electric vehicles], hydrogen, and plug-in hybrid. [Toyota is very] serious about all of them.”

Despite Toyoda’s pledge to be serious about the green shift, new research ranked the world’s largest carmaker the lowest among global competitors on its transition to zero-emission vehicles.

By 2029, only 14 per cent of Toyota’s worldwide production is forecast to be BEVs, according to a recent report from climate think-tank InfluenceMap.

Toyota’s share of BEV production is dwarfed by European peers Volkswagen and Mercedes-Benz, whose electric-powered offerings are expected to make up 43 per cent and 56 per cent of total production, respectively.

Other Japanese automakers look slow in the shift, too. The 2029 BEV forecasts are 18 per cent for Honda and 22 per cent for Nissan. The projection shows the risk that the Japanese auto industry will become a global laggard as the world switches to zero-emission cars. By 2029, the share of BEVs produced by all manufacturers in Japan is forecast by the report to be just 14 per cent — compared with 37 per cent in South Korea, 29 per cent in North America and 59 per cent in Europe.

Toyota also scored poorly on climate policy engagement — receiving a “D” grade on InfluenceMap’s A to F system of measuring against Paris agreement benchmarks. It became the first auto company in Asia to disclose on climate policy activity at the end of last year — a step that improved the transparency metric and raised its overall score from D-.

“Yet [we] have not observed any real-life improvements in their policy engagement, as [they] continue to oppose regulatory efforts to increase the stringency of emissions and fuel economy standards for vehicles across various regions, said Monica Nagashima, Japan country manager at InfluenceMap.

Toyota declined to comment on InfluenceMap’s research. (Tamami Shimizuishi, Nikkei)

Chart of the day

The Federal Reserve last week published a report on the green bond market and the phenomenon known as the “greenium”, a premium price paid when compared with a company’s conventional bonds at the same maturity.

The study found that a greenium emerged in 2019, with interest rates on green bonds about 14 basis points lower than on conventional debt. But, as the FT has previously flagged, the greenium has been eroding. Last year it was only 8 basis points, the Fed report found.

But despite the shrinking greenium, the issuance of green corporate bonds has continued to surge, reaching almost $400bn in 2021. About 6 per cent of all corporate bonds outstanding are now green, the Fed said.

Smart read

-

There has been a plethora of speculation about the impact of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on the energy debate in Europe and America. But what does it mean for Asia? Check out this thought-provoking piece from the BBC on the implications and how it may be accelerating the transition to renewable energy.