Russia’s central bank has slashed interest rates for the third time since early April, taking aim at a blistering rally in the rouble that has seen the currency more than double against the dollar from its March nadir.

The Bank of Russia on Thursday cut its main interest rate to 11 per cent from 14 per cent. The reduction marked a further unwinding of a rise to 20 per cent earlier this year at a time when authorities were attempting to stabilise the rouble after it plummeted in the early days of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

The dash to lower borrowing costs is a sign that Russian authorities are growing increasingly uncomfortable with the rouble’s rapid ascent, investors and economists said.

The rouble’s strength not only belies a struggling domestic economy, which is expected to slump into a severe recession this year, but it puts pressure on government finances by lowering the local currency value of dollar-denominated oil and gas revenues, they argue.

The currency strengthened to 51 to the US dollar this week, a level last seen in 2015, having briefly slumped past 150 in early March. It fell back to around 60 following the rate cut.

“Such an extraordinary appreciation starts to be a financial stability issue, not mentioning risks for economic activity,” said Sofya Donets, an economist at Renaissance Capital. In addition to hurting the government’s budget balance, a strong rouble would make life difficult for some Russian exporters, Donets said, adding that the unscheduled rate cut was “clearly pushed by the rouble strengthening”.

The rebound since March, which has made the rouble the best-performing currency in the world this year, has been driven by stringent capital controls curbing Russians’ ability to buy foreign currency. It has also been spurred by a collapse in Russian imports prompted by unprecedented economic sanctions combined with a continuing flow of energy exports.

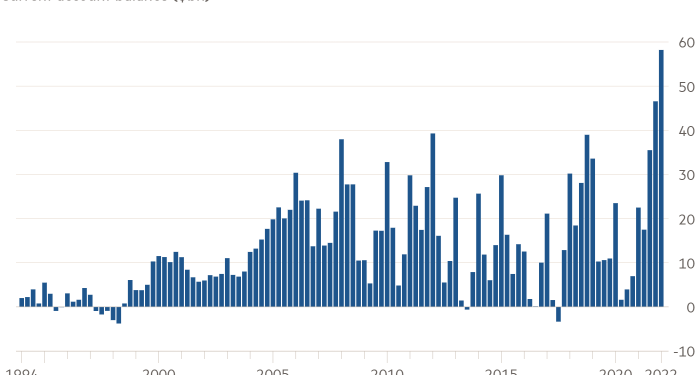

Russia’s current account surplus soared to a record $58bn in the first quarter of 2022, and could climb as high as $250bn for the full year unless new sanctions halt oil and gas exports, according to Elina Ribakova, deputy chief economist at the Institute of International Finance.

“While this is not a free market-determined exchange rate, rouble stability is at the same time ‘real,’ in the sense that it’s driven by Russia’s all-time-high current account inflows,” she said.

The stronger rouble has helped to keep a lid on Russia inflation, which has begun to ease in recent weeks, slowing for the first time since last summer in the week to May 20, according to state statistics. Annual inflation slowed to 17.5 per cent as of May 20, from 17.8 per cent in April, it said.

The central bank said on Thursday there has been a “noticeable decrease in inflationary expectations of the population and businesses”, saying the stronger currency was helping to ease price pressures in the economy. It forecasts inflation will slow to 5-7 per cent next year, and to 4 per cent in 2024. It had previously estimated this year’s inflation at 18-23 per cent.

However, a stronger currency is not a sign of the economy’s resilience to western sanctions, according to Polina Kurdyavko, head of emerging markets at BlueBay Asset Management. Instead, she argues, the rouble rally is actually a sign of the effectiveness of sanctions in isolating Russia from the global economy.

Alongside an exodus of foreign companies from Russia, groups including Russia’s biggest carmaker Avtovaz have been forced to halt production due to a lack of imported components.

“What does rouble strength really mean? Certainly not that the economy is healthy,” said Kurdyavko. “Growth will be deep in negative territory. Inflation is double digits. Clearly pain is being felt. On the most basic level, businesses are closing down because they can’t import anything.”

In this environment, the Bank of Russia will have to tread carefully in seeking to tame the currency’s rise, according to Ribakova.

“Russia’s central bank is trying to loosen capital controls because it feels the rouble is too strong,” Ribakova said. “But the central bank is in a rough spot; if they continue loosening, they may open the floodgates of capital flows out of the country. In previous crises, $200 billion left the country in a matter of months.”

“The bottom line is while the rouble is stable and Russia has a current account surplus in the short-term, the economic fallout from the invasion of Ukraine will undermine Russia’s economy in the long term.”