Welcome back to another Energy Source.

Russia and Ukraine are still dominating the energy world, and in our first note we weigh in on what an EU embargo on Russian oil could mean. Our second, from Amanda Chu, is on the US Securities and Exchange Commission and climate disclosure.

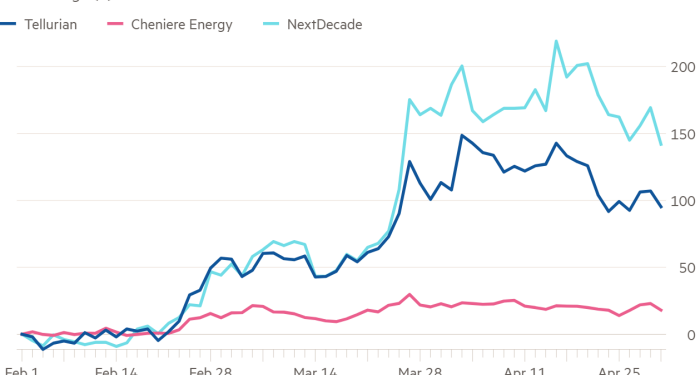

Data Drill follows up more news about Europe’s thirst for natural gas — including a new Engie deal for American LNG — and what this is doing for US exporters’ share prices.

Thanks for reading! Derek

An EU oil embargo on Russia could be the start of much deeper pain

The net is closing on Russian oil exports. Yesterday, Germany said it was ready to stop importing Russian oil “within months”. An embargo across the EU, which buys about half of Russian crude and oil products, will be discussed by officials in Brussels this week. Landlocked member states such as Hungary and Slovakia will need persuading given their long dependence on Russian oil and the absence of easy alternatives. But the direction of travel is plain.

If the move is designed to deny Russia the oil income it uses to finance the war in Ukraine, an embargo is overdue. Russian oil exports accounted for 45 per cent of the federal budget last year.

Production has remained more resilient than expected, despite the so-called buyers’ embargo (as traders shun some of the crude) and the US’s own ban on Russian oil. In March, the International Energy Agency had said that Russian output, above 11mn barrels a day of crude and condensate before the invasion, could fall by 3mn b/d in April alone. But the number has been far less. OilX, an analytics company that tracks global oil shipments, said that output at the end of April was 9.85mn b/d.

Further, Russia’s income from selling oil is holding up. Rystad Energy, a research firm, reckons the Kremlin’s oil tax revenue will rise 45 per cent this year to $180bn due to the spike in crude prices. Since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the EU alone has paid almost €50bn — and rising — for Russian fossil fuel, including more than €20bn on oil imports, according to the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air. That is a lot of money that would be lost to Vladimir Putin’s war chest. The Kremlin would quickly seek to replace it with exports to other more willing buyers.

But there are complications for Russia

-

About 750,000 of Russia’s 2.2mn b/d of crude exports to Europe run by pipeline. Sending that oil to Asia instead would need a costly and time-consuming expansion of export infrastructure. In the meantime, given that Russia lacks much internal storage and refineries are already cutting back activity, fields without an easy export outlet may need to curtail output. Older ones may never restart.

-

Targeting all its oil towards Asia instead of Europe would bring Russia into competition with Saudi Arabia and other Gulf producers.

-

Breaking into other markets will force Russia to keep discounting its oil.

There are complications for the EU too

-

The world is short of spare oil, especially the refined products supplied from Russia. The only two oil regions that could increase supply to fill gaps — Opec and US shale — appear unwilling to do so at the pace needed.

-

If the embargo keeps oil prices high, Russia’s oil income may remain steady even if volumes fall.

-

Russia might retaliate, by ending shipments sooner than planned or cutting off natural gas supplies, sinking the European economy.

-

Breaking its dependence on Russian petroleum will, acknowledged Germany, be expensive. No western politicians have really shown they are willing to tolerate higher fuel prices for Ukraine’s sake. Costly fuel subsidies may be part of an embargo.

An even bigger question is what would follow an EU embargo. Assuming the EU agrees on a ban, it is possible that by the end of the year — if not sooner — Russian oil will have lost almost all its market in the western hemisphere. If so, western countries would have every reason to keep targeting Russian oil exports to other regions. The US’s reluctance to impose the kind of secondary sanctions it previously used to force Iranian oil out of the market stemmed from fears that doing so would damage European allies’ economies. An EU embargo would free the White House from this worry, allowing it to punish other importers of Russian crude.

That’s when the true big cuts in Russian oil production and exports might be expected. The IEA still thinks 3mn b/d of Russian oil will be lost starting this month. Morgan Stanley says 2mn. If an EU embargo is the precursor to a much wider western effort to cut off Russian energy from the rest of the world, those numbers — and today’s oil price — could be far too low. (Derek Brower)

Most US oil and gas producers don’t report emissions to the SEC

Over the past two years, an increasing number of oil and gas companies have opened up about their emissions — but most still won’t reveal their carbon footprint to the US Securities and Exchange Commission.

Only 17 per cent of US onshore oil and gas producers report their emissions to the SEC, compared to 80 per cent that report their emissions in sustainability reports and websites, according to a new survey by law firm Haynes and Boone and consultancy EnerCom. Companies were even more reluctant to report their emissions reduction goals.

“The main difference is essentially liability,” said Stephen Grant, a lawyer at Haynes and Boone. Climate change disclosures in company reports are subject to smaller litigation risk than in commission filings.

The SEC, however, may soon be cracking down on climate-related disclosure. In March, the commission proposed a landmark rule to mandate climate disclosures for all public companies.

If passed, companies would have to file to the SEC Scope 1 and 2 emissions, those created directly by the company’s sources and indirectly through electricity use, as well as other climate-related information in a uniform way for the first time.

In its proposed rule, the SEC stated explicitly that to understand their climate-related risk, oil and gas companies would likely have to report Scope 3 emissions, those created in the burning of products, such as oil, that a company sells. But unlike Scope 1 and 2 emissions, Scope 3 emissions would not be subject to the same liability or attestation requirements.

“The SEC’s approach is addressing a real problem in the marketplace,” said Andrew Logan, senior director of oil and gas at Ceres. “There certainly isn’t good, comparable data to help investors understand the degree to which companies face risk and the degree to which that risk varies between companies in the space.”

Critics argue that the proposal falls outside the SEC’s authority, and its emissions reporting requirements will be highly costly to public oil and gas companies. Since last year, the oil and gas sector has been lobbying the SEC to soften its climate reporting rules.

“The most concerning piece of the proposed rule is what appears to be the targeting of our nation’s fossil fuel companies,” wrote Senator Joe Manchin in a letter to the SEC chair.

“Energy companies don’t disagree with the fact that there can be improvements to the way they do business to have a lesser negative impact on the environment,” said Kit Addleman, a lawyer at Haynes and Boone. “But a general consensus by at least the energy company side is that this is not the way to do it.”

An analysis by ClearView Energy Partners expects the rule’s consequences to be far-reaching, with the potential to shape consumer choices, carbon border adjustment protocols, and proxy battles.

The SEC is soliciting public comment on the proposed rule until at least May 20. If it is finalised, experts expect many lawsuits to be filed against the SEC.

“I think it’s inevitable that this will be challenged by industry,” said Logan. “But I think the SEC has done a lot to safeguard the rule.” (Amanda Chu)

Data Drill

US liquefied natural gas developer NextDecade yesterday signed a 15-year deal to sell the super-chilled fuel to French state-backed utility Engie. It is the first such deal between a US producer and European buyer since Washington promised to lift LNG exports to help break Russia’s grip on European energy markets.

Those that watch LNG markets closely might remember this pair were also at the centre of energy geopolitics back in November 2020. At that time, Engie backed out of a $7bn deal with NextDecade to supply gas from its proposed Texas LNG, in part out of concerns from the French government that US gas was too much of a climate menace to be imported.

It was a major blow to NextDecade and its hopes for building the $10bn Rio Grande LNG plant in southern Texas. But with energy security now clearly back at the fore, the deal was revived.

It’s a clear case of how US LNG developers have seen their fortunes turn in recent weeks. NextDecade’s shares were up 8 per cent on the deal yesterday, and are up more than 180 per cent since mid-February, just before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Other American LNG project developers are seeing investors pile in as well.

Power Points

-

Republicans are working to clean up their party’s reputation on climate change, forming the Conservative Climate Caucus.

-

Vestas, the world’s largest wind turbine manufacturer, says the war in Ukraine will add to the industry slowdown.

-

Australian gas prospectors believe they are on the verge of discovering gold hydrogen.

-

Nearly two dozen senators have called on President Joe Biden to quickly end the Commerce Department’s solar imports probe. (Bloomberg)

-

Greta Thunberg doesn’t want to be the face of the global climate justice movement. (Politico)