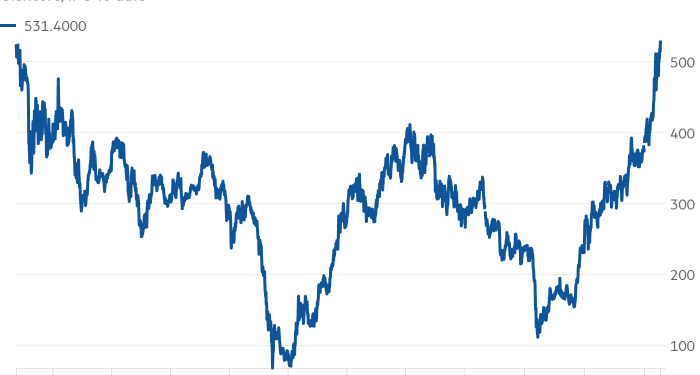

Here’s a chart you may have seen in recent days. It’s the one showing Glencore’s nearly 11 year round trip back to its IPO price.

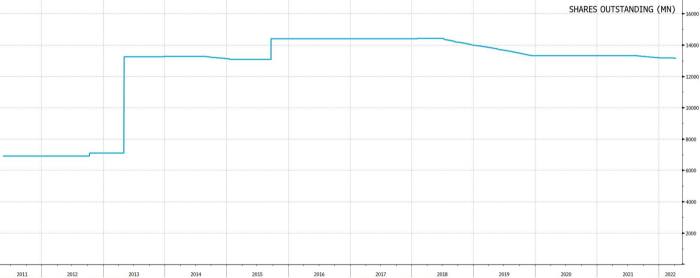

And here’s a chart you probably haven’t seen. It shows Glencore’s shares outstanding over the same period.

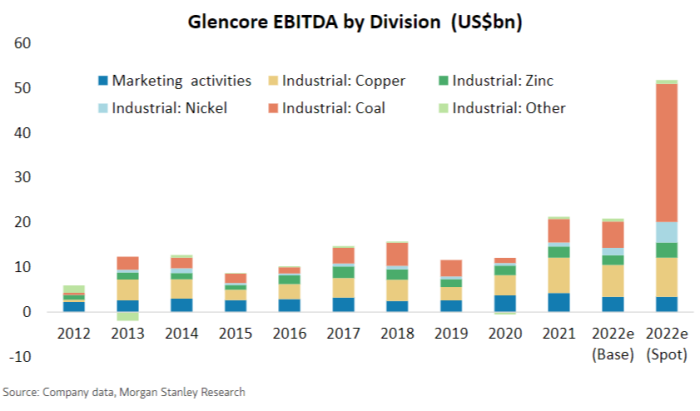

Explaining the first chart is simple. Company-specific regulatory risks are being cauterised at the same time that commodity prices surged, most notably those of coal. As well as being the world’s biggest commodity trader, Glencore is the only Europe-listed diversified miner that offers meaningful exposure to thermal coal, so has been among the ESG-apathetic investor’s wartime stocks of choice. Chart from Morgan Stanley:

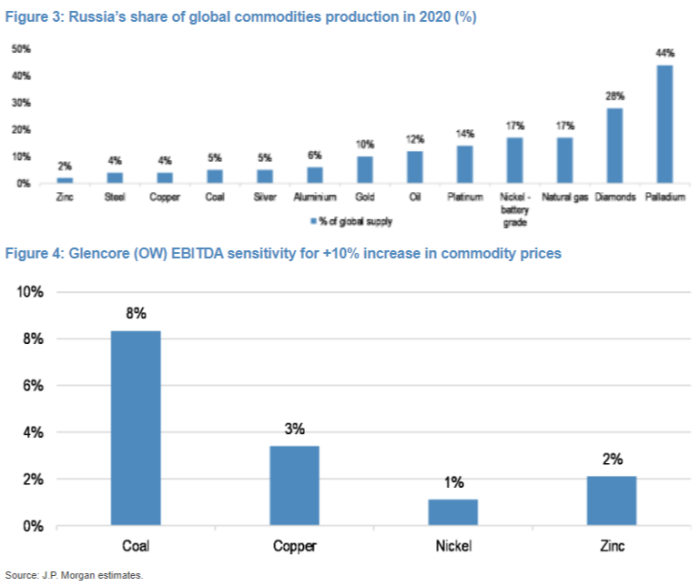

In all, about 65 per cent of Glencore’s production is in Russia-centric commodities, with coal by far the biggest earnings contributor, says JPMorgan, whose charts these are:

Meanwhile, Glencore’s behemoth marketing business tends to make hay in periods of rising prices and volatility. It’s likely to have done particularly well in the year to date because margin requirements are squeezing out smaller traders. And though Glencore’s own trading book will need to run tighter than in 2021, when marketing delivered a record $3.7bn EBIT, the share gains should make the through-the-cycle range of $2.2-3.2bn EBIT easy to hit.

Everyone knows this already, however. The stock’s 43 per cent year-to-date rally (orange line, right axis) has a wholly unsurprising correlation with consensus EPS expectations (cyan line, left axis):

Glencore’s difficult decade can be better understood via the shares outstanding chart, where the big events are easier to spot. Most obvious is a near doubling of the share count in 2013 for the $30bn takeover of Xstrata. After that is a step higher for the cash call at the fag end of the Bric commodities supercycle in 2015, when investor confidence was shot.

Bookending these events are gradual share count declines. The first, beginning in 2014, was on a $1bn share buyback because then-CEO Ivan Glasenberg didn’t want a “lazy” balance sheet. (His definition of lazy wasn’t widely shared: Glencore’s net debt was nearly 10x ebitda when the Xstrata deal completed.) The more pronounced decline starting in July 2018 reflects regular repurchases as Glasenberg and his successor Gary Nagle sought to signal that the company was less worried about bribery and corruption investigations than investors might be.

Zooming into the post-Xstrata period offers a clearer view:

As shown, nearly four years of buybacks have succeeded only in returning Glencore’s share count to where it was immediately before its 2015 near-death-experience. Shares issued back then at 125p have been clawed back over five separate repurchase programmes at prices between 300p and 535p.

In essence, the $2.5bn emergency cash call ended up costing Glencore around $5.2bn.

Which is fine, because what’s done is done. Mining investors want cash returns not value-destroying M&A and top-of-the-cycle capex. Glencore’s buybacks are one element of a formulaic cash return programme seemingly designed to lend confidence that it won’t be buying another Xstrata.

Thermal coal is being managed into gradual obsolescence within the group rather than spun off — Glencore’s target date for hitting net zero total emissions is 2050 — so dirty cash (in the smog sense) can fund a year or two of cash returns higher than any other diversified miner. RBC Capital Markets forecasts a $13bn average annual free cash flow through to 2025, suggesting double-figure dividend yields are possible. Potential disposals, such as a sale of its 49.9 per cent stake in agricultural business Viterra, can add another few billion to the buyback pool.

On the liabilities side, current lawsuit expenses have been capped at $1.5bn and the windfall tax lobbyists have yet to take an interest in coal. There’s always a risk that the marketing division gets on the wrong side of something, but a house value-at-risk limit ($150mn / 95 per cent confidence interval) seems for the moment to be working. M&A remains deeply off limits due to the mess made last time so there really is nowhere for spare cash to go other than back to shareholders.

Dwelling on the after effects of a 2015 rights issue may seem unnecessary, given all that, which is why no one is. Of the 17 brokerages to have issued sellside research on Glencore this year, all but two rate the stock a buy. Investors meanwhile are paying nearly 18 times trailing EPS in a peer group where PEs average about 6 or 7.

Yet for all the guff about Nagle making Glencore more predictable and ESG friendly, the stock’s recovery back to 2011 levels has been almost exclusively powered by the coal spike. A Bloomberg total return analysis screen shows that even with all dividends reinvested, an investor buying in at the IPO was only breaking even at the start of 2022:

A common argument from analysts is that even when the war bonus dissipates, Glencore’s overweighting towards battery materials will make it a better bet than peers over-reliant on iron ore. It’s an image Glencore seems to like, with greenish deals such as a multiyear agreement announced today to ship cobalt to General Motors given the full press release treatment.

But any ambition Glencore has to grow quickly in these areas is hemmed in by Nagle’s rigid dividend policy and through-the-cycle target debt range of $10-16bn, all of which lock in a cash return policy whose long-term value to holders so far has been underwhelming.

As the $5.2bn round trip shows, Glencore’s timing of the market over its listed life has been little better with capital returns than it has been with M&A. Yet shareholders who have a deep resistance honed by experience to any long-term investment seem much more ready to forgive and forget when it comes to getting cash back.