The Bank of Japan has said it will boost its purchases of government bonds over the coming three months as central bankers defend their monetary policy targets even as the yen comes under heavy pressure.

The BoJ said on Thursday it would buy 10-year government debt at a faster pace than it had previously, in a move that follows a series of exceptional efforts to keep a lid on medium-term borrowing costs. The country’s accommodative policy stance sharply contrasts with most other large economies that are unwinding stimulus measures to battle high inflation.

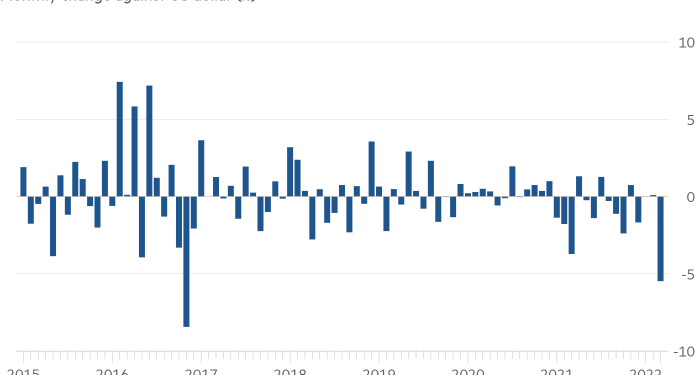

Japan’s yield curve control policy (YCC), where the BoJ looks to keep debt yields in a fixed range, has kept interest rates low in Japan, causing a widening gulf with global borrowing costs. The growing gap, particularly compared with US bond yields, has sent the yen tumbling 5.5 per cent in March, its worst stumble since 2016.

The BoJ’s decision to increase bond buying came on the final day of Japan’s financial year — typically a period of high volatility in bond, currency and equity markets as companies and investors close their books and adjust forecasts and hedging strategies.

But the start to this fiscal year, said analysts, is especially fraught. In addition to the uncertainties created by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, surging inflation around the world and a Japanese corporate sector caught badly off-guard by the yen’s sudden fall, the situation is creating visible tension over the correct policy response.

Currency and bond traders in Tokyo predicted that the new financial year would see markets mounting a series of potentially aggressive tests of the BoJ’s commitment to its YCC policy and the government’s stated faith that a cheaper yen is good for the economy, despite soaring costs of imported energy and commodities and the strain that places on small- and medium-sized businesses across the economy.

The severity of the tests, said traders, would increase ahead of the BoJ’s monetary policy meeting at the end of April, especially if the yen resumed its declines at pace. The problem that would present, said JPMorgan currency strategist Benjamin Shatil, was that the current set-up was not conducive to outright currency intervention — and the market knows that.

“Seeking to cap yields via YCC and the currency via intervention simultaneously is an impossible proposition,” said Shatil who added that the tension between the Ministry of Finance’s discomfort over the speed of yen depreciation compared with the BoJ’s insistence that yen weakness was a net economic benefit had not gone unnoticed.

One question raised by this, noted several analysts this week, was whether the BoJ might eventually be pushed into letting 10-year JGB yields rise, despite its current insistence that the YCC framework was not up for debate.

The prime minister Fumio Kishida faces elections in the summer and, if the impact of a persistently weak yen starts to affect voters and cannot be offset with subsidies, the BoJ’s stance could become a political issue.

So far, the government has played down the idea that it is uncomfortable with the current level of the yen. In his final parliamentary appearance of the 2021 fiscal year on Thursday, Kishida repeated the now familiar line that currency stability was important and sharp exchange-rate moves were undesirable.

The possible consequences of any monetary policy response to yen depreciation, argued Citigroup Japan economist Kiichi Murashima, were not attractive. “Financial markets would almost certainly interpret this as a break with Abenomics. In this case, we would not rule out unexpectedly strong yen appreciation and a fall in equities,” he wrote in a note to investors, referring to former prime minister Shinzo Abe’s flagship economic package.

The BoJ’s announcement on Thursday followed an episode in which the central bank offered to buy unlimited amounts of 10-year JGBs for four straight days in an attempt to force rising yields back into its implicit targeted band below 0.25 per cent after that boundary was reached earlier in the week. Yields in Japan had been rising this week with those in global markets, albeit at a slower pace.

In the January to March quarter of 2022, the BoJ bought ¥425bn ($3.5bn) of 10-year JGBs four times a month. Under its plan for the April to June quarter it will raise the size of each operation to ¥500bn.

The BoJ’s commitment to maintaining YCC, which remains the surviving core of the Abenomics project designed to reform and reignite Japan’s economy, is now among the fundamental factors weakening the yen against the dollar as the interest rate differential between Japan and the US continues to widen.

The yen stood on Thursday evening in Tokyo at ¥121.8 against the US dollar after plunging to a seven-year low of ¥125.1 earlier in the week.

The acute drop, which is underpinned by what analysts called a “triple whammy” of factors, ignited speculation that the currency was approaching the government’s so-called line in the sand where it might feel forced to intervene to support the yen for the first time since the Asian financial crisis in the late 1990s.

Shusuke Yamada, head of Japan forex and rates strategy at Bank of America, said he expected the government would start verbally intervening to support the yen if it weakened beyond the ¥125 level on a sustained basis, but that intervention was not likely until the ¥130 level was reached.