Boris Johnson is pressing ahead with plans to cut the UK’s net carbon emissions to zero by 2050 despite trying to increase North Sea oil and gas production as he faces mounting pressure from critics to ease off on the legally binding target.

In a new energy security strategy expected in the coming weeks the prime minister will set out how the Russian invasion of Ukraine has made him rethink his approach.

He wants to phase out imports of Russian oil and gas and replace them with British production. At the same time, the war has exacerbated a severe cost of living crisis as households face record domestic fuel bills, ramping up pressure on Downing Street to mitigate the cost of the energy transition.

Johnson signalled his thinking at last weekend’s at the Tory party conference, saying he wanted to “make better use of our own naturally occurring hydrocarbons, rather than import them top dollar from abroad and put the money into [Russian president Vladimir] Putin’s bank account”.

“That does not mean in any way that we will abandon our drive for a low carbon future,” he insisted.

But that transition will come at a price. Sir Dieter Helm, a professor of energy policy at Oxford university, warned that politicians have glossed over the long-term costs of reaching net zero. “Pretending the costs do not exist, or that they will all go away in a blitz of new technologies anytime soon, is a dangerous climate change narrative,” he wrote this year.

Some of Johnson’s critics have urged the prime minister to ease off on net zero, arguing that with household budgets under severe strain, now is not the time to load the cost of the transition on the public.

Among those challenging him are the rightwing populists Nigel Farage and Richard Tice, former Brexit campaigners, who are planning to launch an anti-net zero campaign called “Vote Power Not Poverty”. Their views are shared by at least 20 rightwing Tory MPs who form the “Net Zero Scrutiny Group” in parliament.

One of the main demands is the scrapping of the £153 environmental levy on electricity bills, which helps fund the buildout of renewables, to partly offset the expected jump in household energy costs to about £3,000 later this year.

But one ally of Johnson said the prime minister was determined to “face down” the critics and that soaring gas prices only strengthened his case. “Net zero is something he really believes in, it’s one of his guiding missions,” he said.

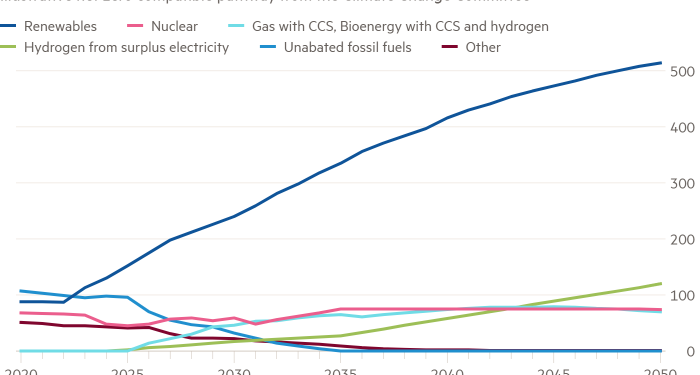

Environmentalists have questioned how Johnson can square his support for net zero with his newfound enthusiasm for the North Sea. But that ignores the fact that the strategy still envisages gas as part of the energy mix by 2050, albeit at much lower levels and with emissions reduced by carbon capture technologies.

One official said the prime minister’s premise was that British gas would displace imports of fossil fuels rather than increase their overall use.

Climate campaigners want a ban on new licences, arguing there is a difference between exploration for new reserves — which can take decades to bring into production — and squeezing more from existing fields.

Johnson recently set out his thinking behind his delayed energy security strategy, insisting renewables would remain the focus and would offer cheaper energy. “Green electricity isn’t just better for the environment, it’s better for your bank balance,” he said.

Antony Froggatt, deputy director of Chatham House’s Environment and Society Programme, agreed. Wind and solar had “moved from being relatively expensive to relatively the cheapest option in many parts of the world. And that is going to continue,” he said.

Yet the calculation is complicated by the “intermittency” of renewables — sometimes there is no sun or wind — which means they need back-up technologies such as battery storage.

The official cost of reaching net zero is put at £1.4tn over the next 30 years. However, that is offset by planned changes — such as insulating homes or the switch to electric cars — that should eventually reduce running costs and generate £1tn of savings, according to the Climate Change Committee, which advises the government.

For now Johnson’s approach to net zero has voter support. A Deltapoll survey found 63 per cent backed his policy with just 8 per cent opposed. Yet more detailed polling suggest that support tails off if people believe they face a personal financial hit.

The cost of decarbonisation in the UK has so far had relatively little direct impact on consumers because it has focused on the electricity grid. Experts warned that future phases of the net zero transition would be more costly to households.

The ban on the sale of new petrol and diesel cars from 2030 will mean drivers having to buy electric vehicles that currently come at a premium.

Households will also have to swap gas boilers for electric heat pumps, which cost around £10,000. But ministers have as yet to set a date for the switchover, nor have they provided much incentive: the existing government scheme offers a one-off £5,000 grant limited to 30,000 households a year.

A report by the House of Lords industry committee this month bemoaned the lack of “credible plans” to deliver net zero. “There is no point planning a carbon-free energy future if you haven’t got a clue how you will get there or how it will be paid for,” said Lord Clive Hollick, the committee’s chair.

The reaction to the “Vote Power not Poverty” initiative underlines how fractious the debate around net zero could become. “Myself and Nigel [Farage] have had more vitriol and abuse than we did during Brexit,” Tice admitted. The campaign launch on Saturday in Bolton, a town in north-west England, was cancelled after two venues declined to host the group.

Environmentalists said Tice and Farage had misjudged the public mood. “It’s awkward timing for critics of net zero who find themselves going out to argue in favour of increasing our gas dependency right when gas is six times more expensive than the clean energy sources they’re trying to stop,” said Joss Garman, UK director of the European Climate Foundation.