Dear reader,

The shortage of chips — and of cars that depend on them to function — is about to get worse. Russia and Ukraine are important producers of two raw materials for making microprocessors: neon gas and palladium. The war between the two countries is likely to choke off supplies. That would exacerbate chip shortages that have already forced the world’s car factories to reduce output.

Ukraine is especially important since it is responsible for most of the world’s supply of neon gas. The country produces more than 90 per cent of the semiconductor-grade neon used in the US. Companies in Ukraine specialise in purifying the world’s neon to the high grades required for semiconductor production.

Neon, once important in the development of laser weapons, is now crucial in powering lasers that engrave tiny designs into computer chips.

Substitution is not easy. Neon, which is a byproduct of steel production, is only found in tiny amounts. Old steel plants built in the 1980s featured manufacturing facilities that capture the gas.

Newer steel factories around the world rarely boast these facilities. Ukraine and Russia are among the few countries that continue to run older plants. Even then, because of the very small amount of neon gas emitted, only a limited number of very large steel plants produce neon.

At the same time, demand from chipmakers has soared, with about three-quarters of the world’s supply of neon being used in this industry.

China, which has always had its own homemade supply, has little surplus for export. It is engaged in a push to wean itself off foreign supplies and become self-sufficient in chips of all kinds.

Neon prices have historically been volatile. They reflect the dire situation today. The price of the gas in the Chinese market has quadrupled from October levels to more than $260 per cubic metre.

Palladium is just as critical in the chip manufacturing process. Russia is the world’s largest supplier of palladium with a 40 per cent market share. The material is also used in emission-control devices in car exhausts, where it converts toxic gases into nitrogen, oxygen, carbon dioxide and water vapour.

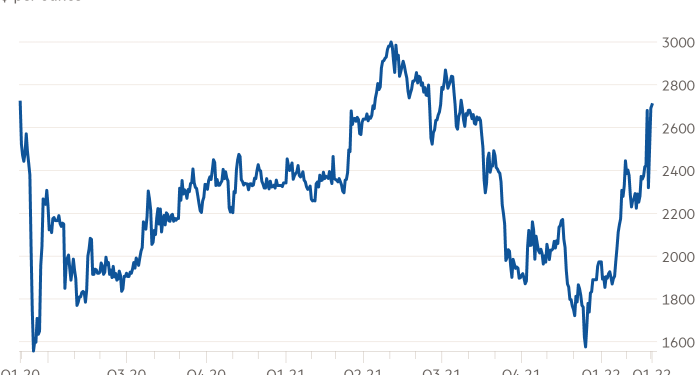

In Asia, where chipmaking is concentrated, palladium prices have long surpassed the price of gold. At $3,000 per ounce last year, palladium cost more than $1,000 more than gold. Supply has continued to lag behind demand, with the shortage reaching about 1mn ounces last year. Signs of a repeat of last year’s price surge is already emerging with spot palladium up 16 per cent since Friday to more than $2,650 an ounce.

So far, there has been little movement in chip prices. Chipmakers typically have two months’ worth of inventory of these materials. The amount of neon and palladium used in the manufacturing process is mercifully small. Long supply chains and lead times mean disruption may take months to appear.

The medium-term risk of supply disruption is high. Shipping materials out of ports in Ukraine is difficult and shipping companies are starting to withdraw services from Russia.

Meanwhile, chemical contamination at Japanese chipmakers last month has exacerbated shortages. Materials at two of US chipmaker Western Digital’s manufacturing units in Japan, which are run by local joint venture partner Kioxia, proved to be polluted, cutting global supply.

All that means higher disruption risks and squeezed margins for chipmakers. The longer the war continues and the deeper western sanctions become, the higher the cost.

June Yoon

Lex writer