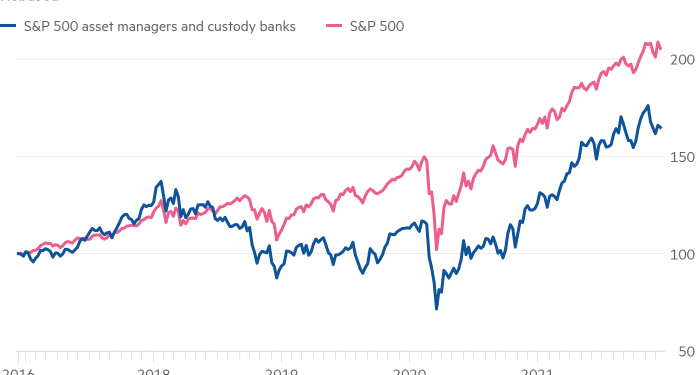

A rising tide of hot equity markets lifted almost all listed asset managers in 2021 but the dispersion between winners and losers is expected to increase next year as investors favour groups exposed to fast-growing areas such as private assets, according to analysts.

“Generally buoyant equity markets and pandemic-related cost savings have provided a significant crutch to asset managers’ earnings [since the] short, sharp market correction in March 2020” at the start of the pandemic, said Tom Mills, an analyst at Jefferies. “A future and potentially more prolonged drawdown would likely be more damaging to operating margins given many managers are now investing for growth.”

Private markets emerged as the hottest area in dealmaking this year for mainstream asset managers, who sought to capitalise on the popularity of these strategies among investors searching for yield, while raising longer-dated capital that typically commands higher fees than public markets strategies.

This month, London-listed Schroders bought a majority stake in renewables investment firm Greencoat Capital for £358m.

The move followed two large alternatives deals in the US: T Rowe Price announced the $4.2bn acquisition of credit manager Oak Hill Advisors in October, and the following month Franklin Templeton said it would buy private equity investment specialist Lexington Partners for $1.75bn.

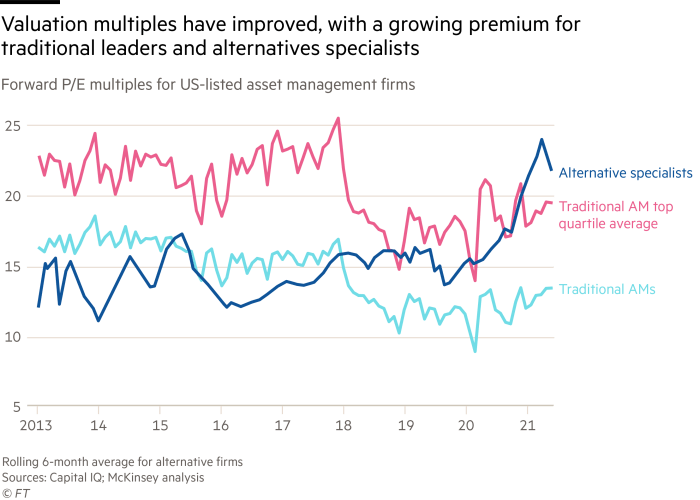

Ju-Hon Kwek, a senior partner at McKinsey in New York, said: “There is likely to be massive variability in the performance of individual asset managers next year,” said . Groups that offer exposure to private markets “are likely to see growth and profitability that’s very healthy in the face of robust client demand”.

Traditional asset management groups have been trying to protect their profit margins as the conditions that drove markets to record highs are poised to reverse.

Fiscal stimulus is being retracted after almost two years and central banks are reining in asset purchases, just as fund houses grapple with the perennial challenges of fee compression and the rise of passive giants such as BlackRock and Vanguard.

“The old traditional stockpicking business, particularly firms that have an undistinguished performance track record will probably continue to be in a painful spot,” said Kwek. “Not only is it facing growth and cost pressure from the continued march of passive managers but it is very exposed to the performance of the stock market. These groups are stuck in the middle and this is where you’re going to see a bit of a squeeze.”

He added that another vulnerable group in a downturn is managers that have opportunistically expanded into “hot” areas such as multi-asset, risk-parity or international investing in the past few years. “There’s a handful of firms who have dabbled and spread out their investments thinly across subscale, non-scalable platforms; the result is high fixed costs and operating complexity.”

Environmental, social and governance-focused strategies continue to grow in popularity with investors. In August, Goldman Sachs Asset Management bought Dutch insurer NN Group’s investment arm for about €1.6bn, attracted by its strong position in this part of the market.

But Mills at Jefferies warned: “The exposure of ESG funds to growth names is quite high.”

“If the promise of interest rate rises is fulfilled next year and we see a switch into a more value-oriented market, there could be performance questions around some of these ESG funds.”

Meanwhile managers have been trying to cut costs through outsourcing. In November JPMorgan Asset Management outsourced its middle office to the parent bank’s securities services division.

“Asset managers will continue to outsource non-core activities because it’s a way to drive down costs and increase the capacity to invest in areas of greater differentiation, like China, ESG and personalisation at scale,” says George Gatch, chief executive of JPMorgan Asset Management. “Anything related to managing money or clients I want to own. Anything else I want to outsource.”