The US must live up to recent commitments to cut methane pollution by joining a new international body to monitor the emissions, according to UN officials involved in the initiative.

The International Methane Emissions Observatory, a UN Environment Programme project, was launched at Sunday’s G20 meeting in Rome, and will offer the world’s most comprehensive, real-time methane pollution data, making it a crucial tool in curbing emissions of a potent greenhouse gas, say its developers.

But the IMEO has been endorsed so far by only the EU, leaving big economies including the US and Japan yet to fully commit, despite their recent pledges to cut methane emissions by 30 per cent by 2030.

“We need their political support more than anything else,” said Manfredi Caltagirone, the observatory’s acting head, referring to the US. “We need those countries that signed up for the 30 per cent pledge to sign up for this. This is the implementation vehicle for the ambition of the pledge.”

Joe Biden entered the White House this year promising to reposition the US at the helm of a global fight against climate change. But slow progress in Congress over a proposed budget bill that would include huge spending on clean energy and delays to a new domestic methane pollution rule could leave the president with little progress to show at this week’s Glasgow climate summit, where methane will be a central topic.

The EU was “proud to support the creation” of IMEO, said Ursula von der Leyen, the European Commission’s president, as the observatory launched. “We urgently need to reduce methane emissions to keep our climate targets in reach.”

The Biden administration did not respond to requests for comment.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change has estimated that cuts in emissions of methane, which has 80 times the atmospheric warming potency of carbon dioxide over 20 years, along with other shortlived pollutants could reduce the rise in global warming by 0.2C by 2040 and 0.8C by 2100.

The International Energy Agency believes about 60 per cent of the 570m tonnes emitted last year stemmed from human activities such as agriculture, energy production and transport, and waste.

While tools to measure methane have emerged in recent months, the new observatory will “assemble the jigsaw pieces” into a complete whole, said Mark Brownstein, senior vice-president for energy at the Environmental Defense Fund, a non-profit organisation involved in IMEO’s development.

The IMEO would focus initially on emissions from the fossil fuel sector, where reductions are considered relatively easy and often cost effective, said Caltagirone.

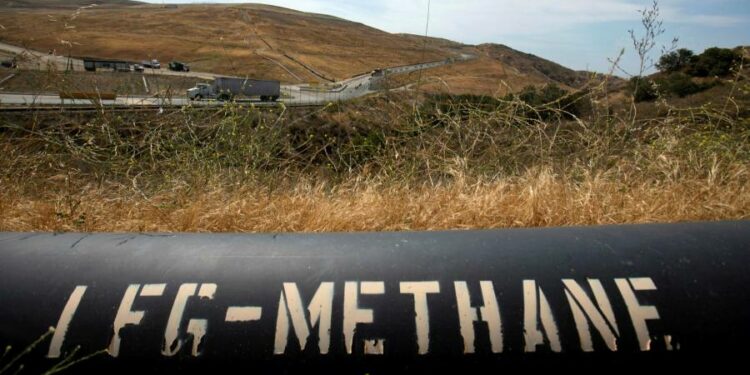

Methane can leak from energy infrastructure or is often vented deliberately into the atmosphere in countries such as Turkmenistan, Russia and the US, where operations can be distant from markets that could otherwise consume the natural gas.

Field studies in the past had often underestimated the amount of methane emitted, but the IMEO would include on-the-ground infrastructure-level data, as well as information from satellites and other sources.

“You need to know what, when and where methane is emitted so you can act on it,” Caltagirone told the Financial Times. “It’s the missing glue that is needed in the system.”

The IMEO will rely on “critical” data supplied by the Oil and Gas Methane Partnership 2.0, a reporting framework for methane pollution.

But of the 74 companies involved in OGMP2.0, only two are from the US. ExxonMobil, Chevron and the big shale oil producers — many of which endorse efforts to cut methane emissions — are not involved.

While the US’s involvement in IMEO and OGMP2.0 has been minimal, the Biden administration has reinstated some Obama-era methane regulations. A new rule cracking down on oil and gas methane pollution would be published “in days if not weeks”, Michael Regan, the head of the federal Environmental Protection Agency, told CNN on Friday.

The US has urged other countries to sign up to the global methane pledge it announced with the EU last month. Although Saudi Arabia, the world’s largest producer, has joined a growing list of countries that have endorsed the target, China, India and Russia, three of the world’s largest methane emitters, have not.

“Without IMEO the pledge risks being just a pledge,” said Caltagirone. The US had an opportunity to “lead by example”, by urging its companies to join the OGMP2.0 as well.

“As the world’s largest oil and gas producer and one of the driving forces behind the global methane pledge, I would think the US would welcome an initiative like the IMEO,” said Brownstein. “You’re talking about a pollutant that is doing a quarter of the warming now.”